by Paul Cudenec

[This is from my new 2024 book Our Quest for Freedom and other essays. An overview can be found here and W.D. James’s preface can also be read on his blog]

A deep sense of the intrinsic lack of value in modern life always lurks somewhere in the hearts of those of us trapped within it.

This is often felt unconsciously, without even being recognised for what it is, but can become more tangible in a variety of guises.

Personally, I can identify the beginnings of that feeling in my reaction, as a child, to the advertisements that sometimes accompanied the TV programmes I enjoyed.

I wouldn’t have used the terms at the time, of course, but I could see that they were vulgar and inauthentic.

Their existence arose purely from material greed – the desire to persuade other people to hand over their money for a product that evidently, left to their own devices, they would not have chosen to purchase.

Different approaches were deployed to this effect, ranging from the basic one of an apparently honest person telling us how good the product was, to glossy image-based efforts associating the product with social or sexual success or more sophisticated humour-based sales pitches.

The first kind was obviously easier to see through, and mock, than the last, but it did not take me long to become aware of the appalling gulf between the surface of whiter-than-white honesty or nudge-nudge complicity and the actual reality of the whole thing being a scam, a lie, with nothing but filthy lucre at its heart.

I had been brought up to be truthful and had been taught by my parents that to misrepresent yourself and your intentions in the pursuit of self-interest, particularly financial self-interest, was a source of shame.

They had been devastated to discover that some friends and I had spent an afternoon knocking on neighbours’ doors and asking to do “odd jobs” on behalf of a youth organisation to which we did not belong.

Even though we had done the “jobs” in question, our dishonesty was a sin and we were made to knock again at the doors in question, this time to apologise and return the coins with which we had been remunerated.

So how could it be, I must have been asking myself somewhere inside, that the adverts on the telly were allowed to do much the same thing?

What did it say about the television channel as a whole that it allowed its airtime to be used to peddle this deceit?

What did it say about our society that we tolerated this, that we considered it acceptable for people to be relentlessly assailed by hypocritical money-motivated lies while they were trying to watch a comedy series, film or football match?

TV can also offer a glimpse of the sheer wrongness of this society through its ‘news’ output.

For years and years somebody has accepted the vision of the world it presents as being broadly sound, or at least based on an institutional duty to try to tell the truth to the public.

Then something happens that makes them alarmed, outraged or angry and they go to the city to take part in a massive protest, alongside thousands upon thousands of like-minded people.

They are inspired by this demonstration of strength and solidarity.

Now the world knows how we feel! Now they’ll have to listen!

On getting home, they switch on the TV to enjoy the coverage of this momentous event.

Only there is nothing. Or ten desultory seconds. Or some cop or politician saying what bad people these were.

This can be a turning point. Why did that happen? Who decided that it should be so? Is everything in ‘the news’ like that? What is ‘the news’ anyway, come to think of it? What is it there for?

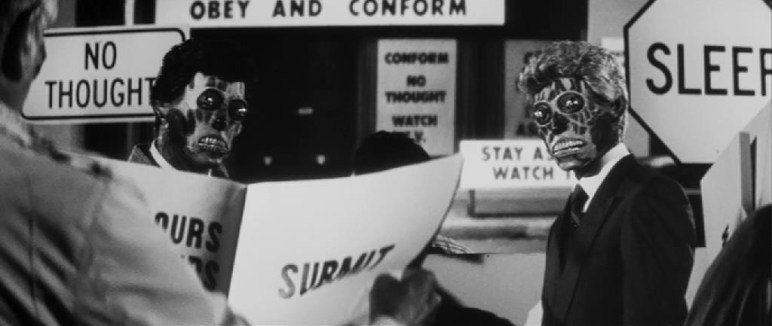

More than that, many of us can smell the hypocrisy of television not only through its adverts and its news, but through every single flicker on its sinister screen.

From its carefully-constructed aura of authority that enables it to define our reality, to its fake bonhomie, its gaslighting denial of the true relationship between it and its public (“see you next week!”), its incessant infantilisation, its sickly visual opulence and its non-stop war on our inner silence and self-awareness, its mission is to turn your brain into mulch.

But it’s not just through the media that we can see the ugly reality of this society – it is constantly staring us in the face if we care to look.

Traffic jams and supermarket car parks. Surveillance cameras and razor wire. Low-flying aircraft and giant billboards.

The relentless routine of drudgery, school days, work days, fleeting moments of freedom before it all starts up again.

Waiting, waiting. Waiting for the weekend, waiting for the good times, waiting for the end times.

Our friends, our conversations, our families. Is there something missing, here? Can’t we go a bit deeper?

Why is that I feel everything is just passing me by, that I am not actually living as I want to live?

The novelties, the adrenalin rushes, the manufactured moments of maximum pleasure – why do they change nothing, why do I still feel so dead inside?

Is this really me? Is this all there is? Was there nothing else to know?

In 2020 this society showed its true face. This was not just on the TV, although the TV played its part. The monster stepped out of its mind-control screens and into our living rooms.

It ripped us apart from our loved ones, smothered and choked us, dragged us screaming from our little everyday freedoms and locked us up, locked us down, in the chilling intention of its dark tyrannical future.

A lot of people realised.

Our Quest for Freedom and other essays can be downloaded for free here or purchased here.

Status chasing or the following of political dogma fills the void of missing identity. People are increasingly tribal in response to conflict, stress, and uncertainty. Empires descend into ethnic enclaves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

La condition humaine.

What you’ve described is the process of anomie (aka alienation etc), which is commonly unconscious and can produce depression (internalised) or aggression (externalised), but when it becomes conscious often kicks off a search for ‘meaning’. As Camus says, when it is realised there is no intrinsic meaning, that can be the beginning of a kind of freedom. Alternatively the search may lead to actual ‘realisation’ – a ‘spiritual’ (higher-level) awakening where everything has meaning.

It’s worth comparing how life was in the stone, bronze and iron ages and still is in many parts of the world and summed up by Hobbes:”nasty, brutish, and short”. Also perhaps consider Shantideva’s advice to King Creet:”It is easier to wear shoes than cover the whole world in leather”. Life is perhaps not about bemoaning one’s station, or changing things, or other people, but transforming oneself – the hardest thing of all – maybe into someone who makes things better for others, in however small a way.

None of which of course is to deny that we have all been had, bigtime, and the world is confirmed as being run by people who – whether they realise it or not – are ruthless exploiters with criminal tendencies and tyrannical intentions, moreover willingly assisted by entire cadres – layer upon social layer – of ‘useful idiots’. But rushing to the barricades is to invite futile martyrdom, so what to do? Perhaps it is enough to be aware, to try to communicate the reality to those still oblivious – as Sisyphus, to keep pushing that boulder up the hill – until something resolves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It doesn’t have to be like that ,.I live in a very rural area and there are quite a lot of people here growing their own food, enjoying nature , and living creative lives, it is being done.

LikeLiked by 2 people