Outright opposition to modernity is often dismissed as backward-looking or “reactionary” and associated with a rigidly hierarchical or aristocratic outlook. But there is another tradition of resistance to the modern world that has very different ideals and can serve as the basis of an old-new radical philosophy of natural and cosmic belonging, inspiring humanity to step away from the nightmare transhumanist slave-world into which we are today being herded. In this important series of ten essays, our contributor W.D. James, who teaches philosophy in Kentucky, USA, explores the roots and thinking of what he terms “egalitarian anti-modernism”.

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon Englandsi mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God,

On Englands pleasant pastures seen!

And did the Countenance Divine,

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these dark Satanic Mills?

– William Blake, Jerusalem, 1808

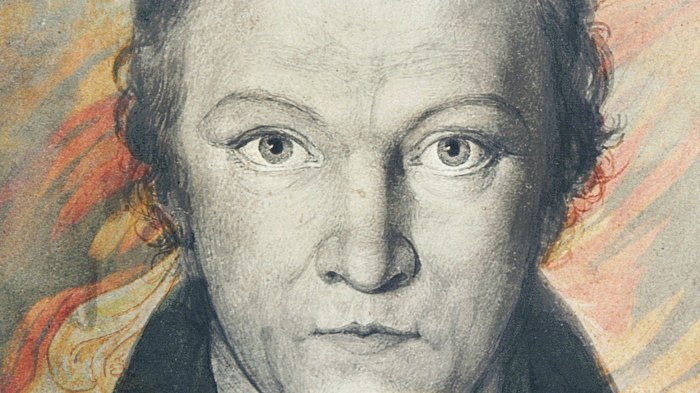

To us living in the postmodern world, perhaps the greatest question is: was modernity, with its promises of enlightenment, liberation, and progress, the fundamental great leap forward of human history or its greatest blunder? Those who give the latter response we can term ‘anti-modernists’. Anti-modernism is, politically, often associated with reaction, oppression, and fascismii. While this can sometimes be the case, I would suggest that there is a whole other anti-modernist tradition characterized by a respect for traditional and indigenous ways of knowing, a nostalgia for organic community, and an ethical commitment to egalitarianism and freedom. William Blake would stand tall in this tradition.

In this and the several essays which are to follow, I would like to point to and explore this ‘egalitarian anti-modernist’ tradition. What is it? Which thinkers belong to it? And what vision and values does it propagate? To get to answers to those and other questions though, a good bit of preparatory groundwork needs to be done. The rest of this essay will be devoted to that.

What is ‘modernity’?

This is something of a vexed or at least contested question. On the one hand, I’ll assume the liberty to highlight what I think are the fundamental characteristics of modernity and on the other depend on my choices being defensible from our historical vantage point of looking backward from our perspective within postmodernity, or late-stage capitalism, as Frederic Jameson termed it.iii I will present modernity as resting fundamentally on a basis of philosophical nominalism which then informs certain fundamental social structures and practices. Next, I will elucidate several subordinate traits stemming from those structures to flesh out the picture and, finally, note several alternative modernities which have not survived.

By ‘philosophical nominalism’ I mean the radical shift in metaphysics (the aspect of philosophy having to do with the fundamental and ultimate nature of what exists) associated with the medieval philosophers Peter Abelard and William of Ockham. Essentially, what they argued was that ‘universals’ don’t exist. By ‘universals’ they meant that common nouns like ‘human’ or ‘table’ don’t actually refer to anything that exists, but that these nouns are just ‘names’ (hence, nominalism, from the Latin ‘nomen’-‘name’) we give to things for convenience or utilitarian purposes. To get at why this matters, we’ll focus on the first example.

Most prior philosophers (and, indeed, most pre-modern peoples) were what are called ‘realists’ in this regard. That is, they felt that ‘human’ referred to something that actually exists (though not concrete): such things are real. Mary, Bob, and Alejandra are individuals, but they genuinely share in something we could term ‘humanness’ or ‘human nature’. They are really, fundamentally, united in this shared reality. Nominalists, by contrast, asserted that Mary, Bob, and Alejandra were really all that exist, and referring to them as all being ‘human’ is just a linguistic custom. This may seem to be merely an academic issue in the most abstruse sense, but it has profound real-world consequences.

While the turn toward philosophic nominalism might have offered lots of new opportunities, it also presented some fundamental challenges. We can see modernity as the attempt to build social and existential order on a nominalist basis. The realist, starting from the belief that there is a shared human nature, began from an assumption that we have fundamental things in common, that there is a natural law (a way of being and behaving according to our shared nature), and that community is part of what ‘fits’ us. The nominalists, on the other hand, recognizing only the reality of a multitude of individuals with nothing real uniting them, faced serious challenges about how to organize their understanding of the world and human societies.

Looking back, we can discern a set of human practices and structures that proved serviceable in organizing people without reference to any transcendent or shared nature or purpose. Historically, these have become hegemonic in the modern world.

In the realm of knowledge, modern, technologically oriented, science became the primary producer of respectable knowledge. Modern science starts from nominalist assumptions. There are no abstract realities that organize nature and entail any sort of natural purposes. There are only the myriad of individual concrete entities which we may classify as we wish and as suits our self-chosen ends. In fact, the postulating of human ends guides all scientific endeavors. How does this thing look to us (vs. how is it in itself)? How can we come to intervene in natural processes, and thus ‘conquer nature’? When Francis Bacon asserted that “knowledge is power”, he specifically and very literally meant this sort of scientific knowledge aimed at technological control. In The New Atlantis (1626), he outlined the future project of modern science to be gaining “the knowledge of Causes; and secret motions of things; and the enlarging of the bounds of Human Empire, to the effecting of all things possible.” “All things possible”, indeed. Never mind whether all things possible are good. In short, we get the disenchanted world of “standing reserve” where nature is laid bare (think of that in terms of the old understanding of ‘Mother Nature’) and subjected to our purposes. William Blake termed this the “single vision” of “Newton’s sleep”, from which he prayed we might be spared. We can more neutrally term this ‘instrumental rationality.’ You get a lot of control and technological progress. But at what cost?

In the realm of politics you get liberalism, in the strict sense of a politics founded upon individualism (remember, only individuals actually exist; as Margaret Thatcher notoriously proclaimed, “there is no such thing as society”). This might take the form of a Lockean liberalism where individuals join themselves together, via a ‘social contract’, to form a limited government to protect their individual rights or of a Hobbesian version where individuals contract to establish a mighty Leviathan to protect them from one another in the “war of all against all”. Either way, ‘society’ is equally a construct, a political technology, people use to organize what was not naturally organized. Here we get our modern notions of individual freedom, but also our experience of the ‘atomized individual’, ‘alienation’, and ‘nihilistic’ fantasies like consumerism and insane fixations on individually constructed ‘identities’. Ultimately, with nothing to genuinely unite them beyond the technological states they create to govern themselves, one way or another, the state becomes the master and the people the administered mass. We get Blake’s:

The hand of Vengeance found the Bed

To which the Purple Tyrant fled

The iron hand crush’d the tyrant’s head

And became Tyrant in his stead.

The “Purple Tyrant” is the tyranny of royal monarchy. The “iron hand” is the Leviathan, the machine, we set up to replace the monarch. It overcomes monarchy (perhaps referencing specifically the regicide of Charles I in the English Civil War), but “becomes Tyrant in his stead.”

In the realm of economics, we get capitalism. Through Adam Smith’s “invisible hand,” markets will assign value and organize production and consumption through virtually an infinite number of individual transactions. There are no overarching moral norms to govern our economic lives, only the economic ‘survival of the fittest’. As Marx recognized, this inhuman structure does lead to unheard of productive capacity. As we also recognize, it does not recognize any moral or natural limits to the exploitation of the natural world or of human beings (which really have no qualitatively distinct status given ‘human’ doesn’t refer to anything real). Here we have Blake’s “Dark Satanic Mills” where there should be “Mountains green” and “pleasant pastures”. Humans are just ‘standing reserve’, or ‘human resources’, as is everything else. Human beings as gods (masters of nature) end up reducing human beings below the level of human beings. There is a dialectic for you.

Finally, in the realm of ethics, or about the only kind of pseudo-ethics you can construct on this foundation, we have utilitarianism. ‘Happiness’ is reduced to ‘pleasure’ (which is supposedly empirical and quantifiable), and we somehow are supposed to derive an ‘ought’ that would lead us to whatever would produce, according to Jeremy Bentham, “the greatest happiness for the greatest number”. While you can formulate prescriptions on that basis, what in the world would compel you, as an individual among other individuals, to sacrifice your own interest to this interest of the greatest number? To paraphrase the friend of Adam Smith, David Hume, there is nothing irrational in preferring the desolation of millions to the pricking of your own thumb. As Blake lamented, “God forbid that Truth should be confined to Mathematical Demonstration.”

To fill out our picture of what constitutes modernity or the modern world we can note several other phenomena which seem characteristic of these hegemonic formations. For instance:

- The centrality of the metaphor of the ‘contract’ in the organization of the political and economic spheres. What else would be the basis of two distinct individuals cooperating?

- The development of ‘bureaucratic’ structures to technologically coordinate human activity. There is nothing about human beings as distinct material objects to yield them immune to technological control.

- The development of ‘propaganda’ to “bring order out of chaos”. Propaganda forms the “executive arm of the invisible government”, to quote Edward Bernays, one of the first theorists of this ‘science’.

- Technological development and dominance.

- The application of technological knowledge to production, yielding ‘industrialization.’

- The ideal of ‘rational autonomy’, derived from Immanuel Kant, but which given the realities of bureaucracy, propaganda, technology, and industrialism, ends up amounting to a consumerist and scripted fashioning of individual identities.

We can see all of these as more or less necessitated developments to impose an order upon the metaphysical disorder introduced by nominalism.

Did modernity have to end up with this particular hegemonic regime? Maybe, maybe not. There were attempts to construct other modernities. Marxian communism was one. Marx sought to build on the accomplishments of bourgeois modernity a social reality that would exploit the productive capacity unleashed by liberal, bourgeois, capitalism to social and human ends. Historically, that option has failed to be realized and is largely seen as discredited. Another was fascism. Fascism attempted to replace, functionally and psychologically, the vanished organic community with the totalitarian state and a nationalist identity. Typically, fascist regimes sought to restrain and channel the energy of industrial capitalism in a more socially harmonious direction via ‘national socialist’ or ‘corporatist’ means.iv Yet, again, history has not been kind to the survival of fascistically organized regimes.

For all intents and purposes, I will assume when defending a version of anti-modernism, that modernity consists of the hegemonic dominance of a framework characterized by liberalism, capitalism, instrumental rationality, and utilitarianism along with the subordinate ordering structures noted.

Anti-modernisms

So, what will constitute a type of thought as being ‘anti-modern’ as opposed to ‘postmodern’ or ‘critically modern’ (where I would situate Marx; affirming much of the modern while trying to critique it so as to produce a more humane or more rational outcome)? Central to this is a rejection or critique of having made the modern move in the first place.

Such thinkers will then, firstly, appeal to the preferability of either (a) a pre-modern form of social organization (such as medieval or tribal structures) or (b) a primordial reality held to be superior to modern conceptions (as reflected in a notion of Nature or of Mythology). The positive attributes of this pre-modern situation will be used, secondly, to critique modernity and to prescribe a solution that draws upon and re-establishes these pre-modern values. This does not necessarily necessitate a return to a pre-modern condition, which we could legitimately describe as ‘reactionary’, but which at least draws upon those pre-modern or primordial realities to formulate an improved alternative to modernity. I’m sure this sounds rather abstract, but we’ll seek to fill in details as to how this looks, more concretely, as we examine specific anti-modern writers in future essays.

Among those who adopt an anti-modernist stance, we can then make a fundamental distinction. Such writers will tend to fall into either ‘egalitarian’ or ‘aristocratic’ camps. Perhaps this reflects an allegiance to one or the other of the primary social classes of the feudal order: the peasants or the nobility.

Aristocratic anti-modernists will typically uphold the values of nobility, strength, will, hierarchy, and power. Joseph de Maistre and Thomas Carlyle might be seen as the founders of this strand of anti-modernism. Though it is a sticky question whether Friedrich Nietzsche was anti-modern, later aristocratic anti-modernists will tend to draw upon him. In this camp we can situate such thinkers as Julius Evola, Ernst Junger, and Alexandr Dugin (pictured). Often ‘anti-modernism’, per se, is equated with this strand of thought. Though even here, simply labelling it ‘fascist’ (as part of the contemporary regime’s smearing campaign) is at least simplistic, if not misguided. For instance, Evola claimed to be to the right (!) of fascism, Junger was a Conservative Revolutionary, but explicitly anti-Nazi, possibly to the point of participating in the failed attempt by German higherups to assassinate Hitler in 1944 (though the circumstances surrounding this are still historically murky), and Dugin (regularly labeled a fascist in the media) explicitly rejects the label and actually has a highly developed and interesting anti-racist anthropology. Be all that as it may, this is one fundamental anti-modernist option.

Egalitarian anti-modernists, on the other hand, tend to emphasize organicism, communalism (what Paul Cudenec terms ‘withness’), the intrinsic inestimable value of each unique person, a preference for what is common (in the double sense of what is shared and of what is lowly), cooperation, freedom, the dignity of actual producers, and a wholistic approach to nature and our embeddedness within her. The fathers of this strand of thought are Jean-Jacques Rousseau and William Blake. Other seminal thinkers would include folks like Henry David Thoreau, John Ruskin, William Morris, Leo Tolstoy, GK Chesterton, Ananda Coomaraswamy, Mahatma Gandhi, Simone Weil, Jacques Ellul, JRR Tolkien, Ivan Illich, EF Schumacher, and Wendell Berry. This is the alternative anti-modernism it will be my task to outline, explore, and defend in what is to follow.

In future essays, I will explore several of these thinkers in-depth. At this point in history, it should be pretty clear to us that we have collectively taken a very wrong turn somewhere along the line. My belief is that this set of thinkers (and others like them) can help us gain a better understanding of how deep our problems lie and to recover a vision of a humane and free future we might work towards. First resistance, then creation.

i This is Blake’s spelling, not the more common ‘England’s.’

ii The association of fascism with anti-modernism is often wrong, or at the very least, the question is complicated. See Zeev Sternhell’s The Birth of Fascist Ideology (1994) for a discussion of fascism’s embrace of modernity, especially of aesthetic Futurism.

iii I follow Jameson in seeing ‘post-modernity’ as more an end-stage, final, or ultimate development of the modern, and hence not really after it.

iv See The Doctrine of Fascism by Benito Mussolini (and ghost co-authored by the philosopher Giovanni Gentile) where he explicitly argues that the State creates the People, and is, hence, ontologically superior to the People and is to be overtly “totalitarian”: The doctrine of fascism : Mussolini, Benito, 1883-1945 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Very interesting essay. I look forward to the others. Your “anti-modern egalitarians” should also include Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975), for whom the theme was one of the truly dominant ones of all his poetry, films, essays, and novels. Henry Miller should also figure in that list. As well as late 20th-century US poets John Haines and Robert Duncan, to go along with Wendell Berry. And I would also include the contemporary French novelist Michel Houellebecq, though he is sometimes problematic in other respects. And Baudelaire.

There are probably many more as well. A contemporary Italian poet-critic, Gianni d’Elia, writing about Pasolini, also came up with the formulation, in his regard, of “the avant-garde of tradition.” This would also fit many of the above.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Who D. Who, Thanks for the thoughtful and constructive comment! I love the ‘avant-garde of tradition’ idea. I suspect you’re correct about Pasolini and the others. Hopefully, others will also put forward candidates we should consider as part of this tradition. While the future essays will focus on just a handful of thinkers, a lot of others will receive at least a passing mention. Besides Blake and William Morris, some musicians will be about as far as I go towards more strictly literary figures though. I appreciate your insights in that direction.

LikeLiked by 1 person