by W.D. James

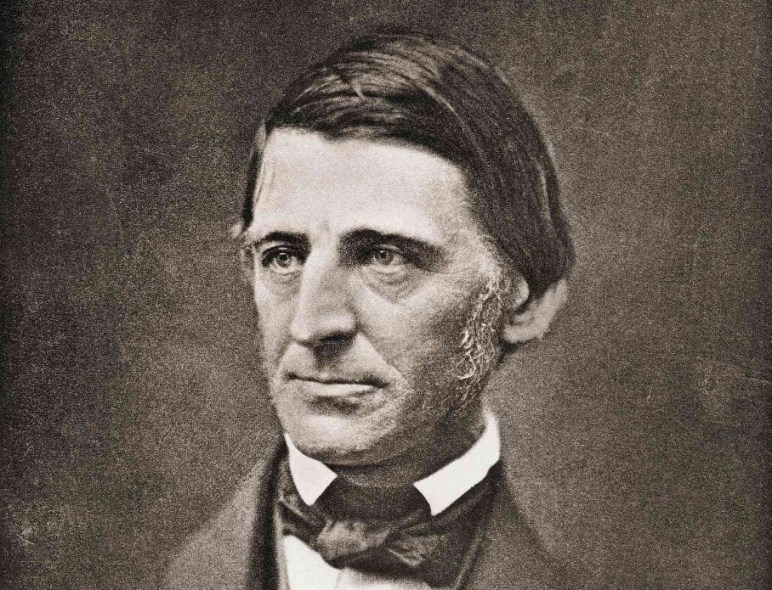

In this series of reflections on America and ‘the faded republic,’ which I believe lies, now obscured, at its heart, pride of place should go to Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882). ‘The Sage of Concord’ is arguably our most original genius and called us forth to realize who we really were, as he saw it, as Americans.

(‘The Old Manse,’ home of William, Sr., and Ralph Waldo).

Two revolutions?

Through one of the more serendipitous conjunctions of history, Emerson was born and lived in Concord, Massachusetts. His grandfather, William Emerson, Sr., was an ardent patriot and was at the Battle of Concord at the initiation of the American Revolution. William was Concord’s minister and active in the militia.

On April 19, 1775, he was on the field in Concord as the British regulars, having earlier routed a small band of militia at Lexington Green, advanced against a more substantial body of minute-men. They would advance no further that day and would soon be in panicked retreat back to their barracks in Boston.

Accounts vary as to whether William was physically among the militia or on his front lawn. That he had built his home next to the North Bridge and that the patriots had formed up at the North Bridge probably explains that – the battle was pretty much at his house. Emerson’s father, still a young child, was inside the home.

After this engagement William rode to nearby Boston and was appointed chaplain to the fledgling army taking shape there and besieging the surrounded British army holed up in the city. After a few months he came down with dysentery and died on the return trip home.

So, Ralph Waldo had a direct connection to the beginnings of the war which would establish the external, political, freedom of the country. From Concord he and his fellow ‘Transcendentalists’ would seek to complete that project by affecting an internal revolution that would perfect the nation and its people.

The Transcendentalists, of whom Emerson was the undisputed informal leader, can be seen as rebelling against the philosophy of the first American Revolution which they understood to have been rooted in the empiricism of John Locke with its emphasis on self-interest. Against this they made use of the new German philosophy of Idealism, largely as interpreted by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Emerson’s fellow Transcendentalist George Ripley, also a fellow Unitarian minister, who founded the utopian community of Brook Farm, summarized the intention of the movement as being “the assertion of the high powers, dignity, and integrity of the soul; its absolute independence and right to interpret the meaning of life, untrammeled by traditions and convention”. 1

Against ‘self-interest’ Emerson posed ‘self-reliance.’

This revolution in philosophy and especially in the understanding of who or what the individual was, would, they believed, complete the external revolution by effecting an internal one which allowed for the realization of the hidden or latent potential of the first.

Individualism

Americans like to think of ourselves as individuals. America is the land of the ‘rugged individual’ after all. We often like to think of ourselves as absolutely unique and hence of unique value. We like to stand out, or think we stand out, from the herd. Our own special creation.

On the political level we think of ourselves as people with individual rights that allow us to live however we choose and which limit the claims society or the government can place on us.

There are two related problems that stem from these conceptions. First, if we’re each absolutely unique, by what standard would we assign any particular value, that we or others would recognize, to the creation we make of ourselves? Secondly, the more atomized we become socially, ironically, the more conformist we become. We define ourselves in comparison to others and/or through the creation of a ‘life style’ mainly reflecting our choices of consumption.

Emerson, in his essay “Self-Reliance,” understands both of these issues and wants to figure out what an authentic individualism would entail.

The American Renaissance

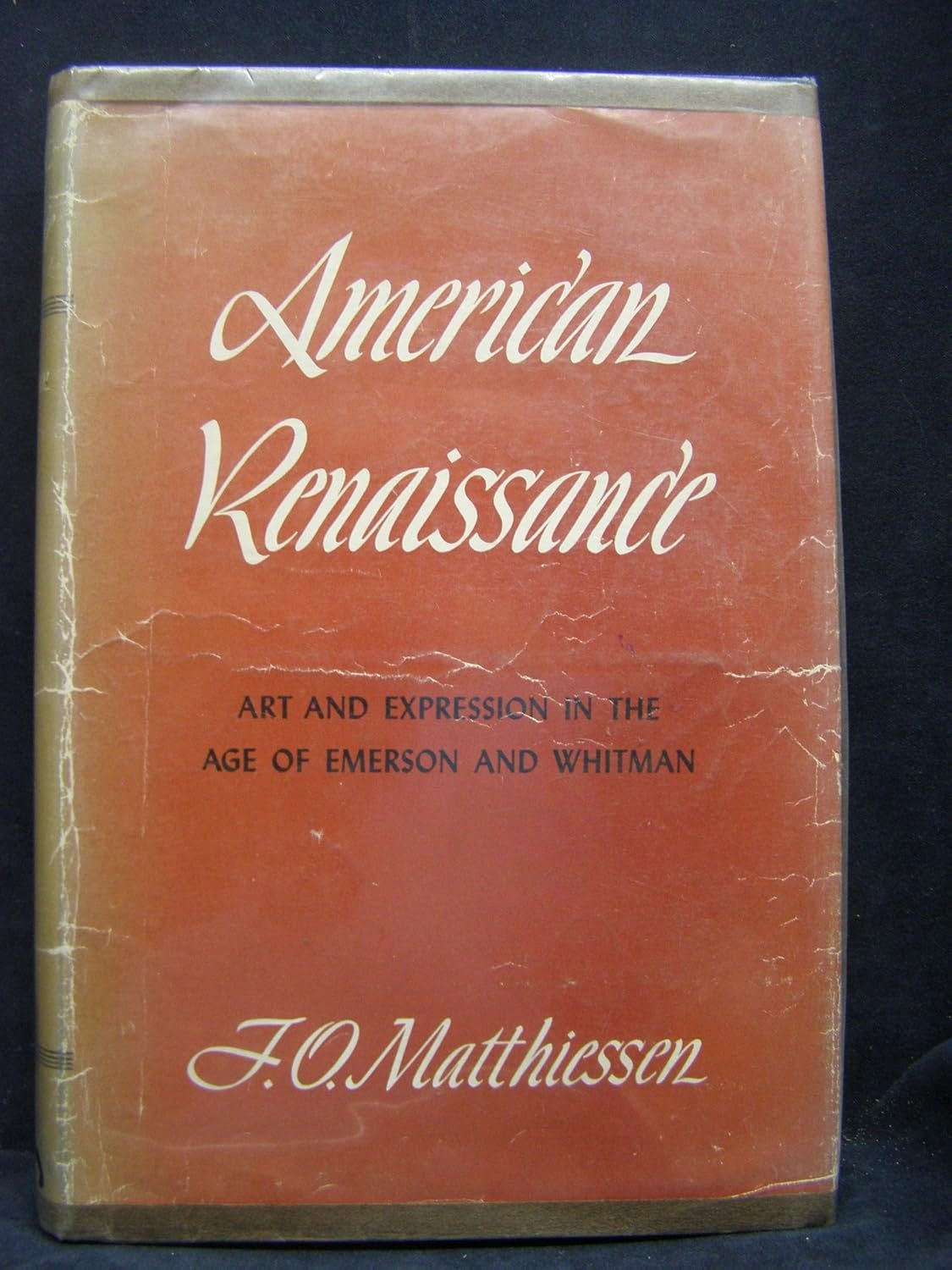

Emerson is a key thinker in what later cultural critics would term ‘The American Renaissance.’ Others included under that heading would be Emerson’s friend and younger colleague Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville and Edgar Allen Poe.

These writers represent the foundation of a specifically American way of thinking, at least according to critics like F. O. Matthiessen. Though the idea of an ‘American Canon’ has been under heavy assault for the past several decades, it was folks like Matthiessen who established that there was one and that writers like these comprised its core.

What he said connected them all was “their devotion to the possibilities of democracy”.2 Specifically, they delved into the deeper problems and implications of an egalitarian society. Was it consistent with human nature? If so, what was that nature?

In seeking to answer those questions, this set of thinkers laid the foundations for an indigenous literature, philosophy, art, and architecture, mostly unconstrained from European traditions and conventions. And, even more importantly, they created a conception of human beings of which America, or a properly reformed America, could represent the fulfillment.

Put somewhat less pretentiously, they saw within the newness of America a unique opportunity for humanity to start again in a pretty fundamental way. Perhaps here, unencumbered with thousands of years of tradition and custom, we could learn to live closer to how Nature intended.

Self-Reliance

Emerson begins his essay, written to be delivered as a lecture, with an exhortation for his readers or listeners to think and live as honest, authentic individuals within a society that paid lip service to individuality but which in fact prized social conformity.

Emerson asserts that “To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart, is true for all men – that is genius” (p. 113). That formulation might already strike us as strange for a couple of reasons. One, it starts off sounding like the sort of subjectivism undergirding statements like ‘what is true for me, might not be true for you.’ But then it ends up saying that what is true for me is actually true for you. It also might sound like the maxim to ‘believe in yourself.’ It is, but what we start to detect is that Emerson’s conception of the self present in ‘yourself’ may not be the same as in our modern popular adages.

He famously goes on to criticize social conformity. “Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members,” he famously states. “Society is a joint stock company in which the members agree for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater. The virtue in most request is conformity. Self-reliance is its aversion.” “Whoso would be a man,” he continues, “must be a nonconformist” (p. 116). Later he laments “If I know your sect, I anticipate your argument” (p. 118).

I think that last line gives us a good insight into what Emerson is on about here. I’m sure we’ve all had the experience of someone simply conforming to ‘the party line’ whether that was a political line, a religious line, or something else. From the other end it might go something like: well, I’m a feminist (or anti-feminist); feminists (or anti-feminists) are supposed to be for this and against that; guess I’m for this or against that.’ Or, ‘I’m a Baptist (or Catholic, or Baha’i) and we Baptists (etc…) think such and such.’

The problem is we may never get around to figuring out what we actually think and who we actually are. Further, no one else will actually know what we think or who we are either. We might think of ourselves as an individual, but we haven’t actually become individualized yet.

The Self

What is the self that Emerson thinks is, or should be, capable of self-reliance (that most American of values)?

He speaks of “that divine idea which each of us represents” (p. 114). He asks, “What is the aboriginal Self on which a universal reliance may be grounded” (pp. 122-123)? What is this ‘divine idea’ and what is the warrant for trusting it?

He associates the ground of the Self with “Spontaneity,” “Instinct,” and “Intuition” (p. 123). He continues, “We first share the life by which things exist, and afterward see them as appearances in nature, and forget that we shared their cause…. We lie in the lap of immense intelligence, which makes us organs of its activity and receivers of its truth. When we discern justice, when we discern truth, we do nothing of ourselves, but allow a passage to its beams” (p. 123).

Elsewhere Emerson will call this “immense intelligence,” “Nature” or the “Oversoul.” He is alluding to the fact that we are in fact not distinct from ‘nature;’ we are manifestations of the same ultimate causes by which all else exists as well. There is a deep affinity between our Reason, or Intuition, and the world around (and within) us. When we discern justice or truth, and we could add goodness, beauty, etc…, it is really Nature or the Oversoul, as present within us, recognizing its own nature on his view. That should be about enough to blow a person’s mind.

In fact, for Emerson, it is not at all out of place to speak of the Soul as divine. “The relations of the soul to the divine spirit,” he avers, “are so pure that it is profane to seek to interpose helps” (pp. 12-124). Such ‘helps’ would be things like traditions, formulas, creeds, churches, etc….

So, on the one hand we can see why Emerson thinks the Self, the individual Soul (which is a particular manifestation of the Oversoul), is trustworthy. On the other hand, we can see why he is so critical of conforming our selves, our thoughts, our will to ‘Society’ or, we might add, ideologies. They can only distort what is by its nature pure and sacred conformity to Nature, Truth, Justice, etc….

A way as rude as America

This does not mean that Emerson thinks there is not effort involved in actually giving voice to our authentic selves or, indeed, in becoming authentic selves. Absolute integrity is a task.

Emerson can sound notoriously hard-hearted, such as when he says “do not tell me, as a good man did to-day, of my obligation to put all poor men in good situations. Are they my poor?” He goes on: “There is a class of persons to whom by all spiritual affinity I am bought and sold; for them I will go to prison, if need be; but your miscellaneous popular charities; the education at college of fools; the building of meeting-houses to the vain end to which many now stand; alms to sots; and the thousandfold relief societies…” are no business of his, he claims (p. 117). Though he was an abolitionist who spoke in defense of that cause (and entertained John Brown in his home), he can also ask what matters it to him the fate of a “negro” a thousand miles away.

What I think he is talking about is that our ‘goodness’ can also be inauthentic. We can do it for show. We can do it to conform to social expectations. That he will have nothing to do with. Only if the poor are his poor will he help them; that only if his honest conscience tells him to help will he help. In fact, if need be, he will suffer and go to jail for them, but he won’t help out of someone else’s expectation. A bit edgy.

He also rails against consistency. He calls it the “hobgoblin of little minds” (p. 119). If I honestly believe differently today than I did yesterday, why should I not speak the truth as I perceive it now? Consistency is one trap that can lead the soul to not be honest with itself. Some of those traps may be set by others, by society, but some can be set by ourselves as well.

The authentic self will reject false standards and, he observes, society will take this as a rejection of all standards, what he terms “mere antinomianism” (p. 127). But the authentic self will live by its own standards which Emerson thinks will be much higher than society’s.

Emerson is recommending a path to authentic selfhood that is rude in at least two ways, ways that are, I think, rooted in his view of America. First, it may come off as gruff, course, obstinate. Americans can be direct like that. Secondly, it is rude as in unrefined, unstudied – as rude as nature.

In fact, he admonishes his fellows to not go chasing after foreign fashions or importing foreign standards. “Beauty, convenience, grandeur of thought, and quaint expression are as near to us as to any, and if the American artist will study with hope and love the precise thing to be done by him, considering the climate, the soil, the length of the day, the wants of the people, the habit and form of the government, he will create a house in which all these will find themselves fitted, and taste and sentiment will be satisfied also. Insist on yourself; never imitate” (p. 132).

A community of true selves

Emerson can be read as a proponent of what came to be termed the ‘Imperial Self.’ Essentially, the selfish self that also became an American ideal in the later Gilded Age. Are Emersonian selves to be closed in upon themselves?

In his essay on “The Over-Soul,” he speaks of “that Unity, that Over-Soul, within which every man’s particular being is contained and made one with all other; that common heart; of which all sincere conversation is the worship, to which all right action is submission, that overpowering reality which confutes our tricks and talents, and constrains every one to pass for what he is, and to speak from his character and not from his tongue; and which evermore tends and aims to pass into our thought and hand, and become wisdom, and virtue, and power, and beauty” (p. 187).

One usually has to read one Emersonian essay ‘against’ another to get his whole meaning or the whole picture he has in mind. In this case, we can see how his very conception of the soul that makes it imperative for it to be authentically individual also makes it necessarily connected to all other souls. Yet the relations must be authentic. A higher, truer conception of society emerges, not one which is a conspiracy against the ‘manhood’ of each member but one in which each is genuinely present to one another with well-formed characters.

Inner meanings

What Emerson is doing is drawing out the inner meanings of Americans’ external existence. From its founding America was individualist in the sense of protecting individual rights. But what, Emerson asks, is an individual?

America was republican at its founding and was becoming increasingly democratic in terms of things like expanding the franchise. But what, Emerson asks, is a true people?

What he saw was that America’s institutions of themselves were not necessarily bearing good fruit. What sort of people would we need to be to turn external freedom and equality into an actually good culture and civilization? That is, what was the hidden and internal essence of our external framework?

Emerson thought we must have the courage to grow into people of genuine integrity rooted in our natures. We must be austere enough to deal with one another honestly. We must not conform to the mass. Only if the mass was in fact not mass, but a field of genuinely formed individuals, could things like constitutions and institutions and democratic cultural norms bear good fruit.

What I have been calling the inner or internal essence could also be called the spiritual essence. ‘Democracy’ tends to be conceived of materialistically and quantitively – the majority wins. Emerson was trying to help us see that the material and quantitative alone are insufficient. There are spiritual realities involved and only by paying attention to, cultivating, and prioritizing those could the actual potential of America be realized.

From his home by the North Bridge in Cambridge he was not so much advocating a second American Revolution as trying to show people what it would take to make the first one work and justify itself.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo, Essays and Poems by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Barnes and Noble Classics, 2005.

Quoted in Gura, Philip F., American Transcendentalism: A History, Hill and Wang, 2007, p. 14.

Matthiessen, F. O., American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman, Oxford University Press, 1941, p. ix

I ordered the book today, great roundup of this most interesting man, sight beyond sight so to speak. Sorry to say the Bruce video just doesn’t make it for me as he has shown us his true colors and feelings about this country after fooling folk for years to buy his below par music IMHO. Thanks again JD for the insight, and all the best in this most important struggle we are about to embark upon all across the western world, who will win only God knows.

LikeLike

Thank you Moringa Man. The issue you mention with Bruce actually weighs heavy on my mind – even more so in the case of Neil Young (and there are others). The past 5 years have not been good to many of my old musical heroes (Van Morrison and Roger Waters came through better, but took heck for it). I’ve decided I’m not willing to reject their earlier great music based on their later failures. In this case that means something like I’m not willing to remove his Nebraska Album from my life because he had later failures. I’m not saying that is the right response, just where I’ve come to in struggling with this. It’s a real issue though and I feel ya. W.D.J.

LikeLike