by W.D. James

What is the US South?

In 1930, a group of ‘Twelve Southerners’ published a manifesto in defense of Southern culture. They called the anthology of twelve essays “I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition.” The contributors were primarily literary folks, most of whom had connections to Vanderbilt University. They came to be known as ‘the Southern Agrarians’ or ‘the Nashville Agrarians.’

The most prominent members were John Crowe Ransom, Donald Davidson, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren. They helped trigger a revival of interest in Southern culture and a renaissance in Southern literature. In this essay I would like to focus on the Statement of Principles they prefaced the essay collection with.

“I’ll Take My Stand,” will be a core text to anyone who wants to seriously study the American South and its culture. However, to understand it and to understand the intentions of its authors requires an exploration of Southern culture back to the founding of the nation.

While that is clearly beyond the scope of a single essay, I will follow a thread that far back. I am on record as being a defender of Southern culture, especially that of Appalachia, but most of all of Southern music, black and white, in general.

Have I mentioned the South can be tricky to understand and to grapple with?

To start with, I’ll look at what Southern agriculture is, or was, and the two ideals which defined it. I’ll then examine how those two ideals, while having some natural affinities, relate in almost opposite ways to the question of slavery in Southern agriculture and culture more broadly.

We’ll then trace the interconnected threads of those two ideals as they came to inform the ‘Lost Cause’ ideology of the post-Civil War South on the one hand but also America’s most democratic and anti-capitalist strand of native thought running from Jeffersonian and Jacksonian democracy to the agrarian populism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries on the other.

Next, we’ll examine in detail how the principles of the Southern Agrarians fit into that broader picture and what they might have to still teach us.

Finally, we’ll look at how the cause taken up by the Twelve Southerners was also lost and how that second Southern defeat still ripples through American cultural values and how it cost us the intellectual edge of our native critique of modern industrial capitalism.

The Gentleman and the Yeoman

The Southern colonies self-consciously set out to establish a culture centered on agriculturalism. While most people in the Northern colonies were also farmers, the North was always more open to trade, manufacturing and commerce. In the nineteenth century that would lead to the explosion of the Northern cities (largely through immigration, which also made them more cosmopolitan) and industrialism.

Two ideals governed the establishment of Southern agriculturalism. There are inherent tensions and contradictions imbedded in these two ideals which point to many of the inherent tensions within Southern culture for the first four hundred years of American history and which are not totally resolved yet.

One idea was that of the aristocrat or the country gentry. In this regard, some Southerners set out to emulate the landed aristocracy of the Old Country. To a considerable degree, they actually were the landed aristocracy of the Old Country.

This operated in three distinct ways. First, there were actual English aristocrats with large property holdings in the colonies. However, these folks usually remained back in Britain though they may have sent relatives or trusted retainers to look over their holdings. Secondly, there were members of English aristocratic families who came to the American colonies and sought to constitute themselves an aristocracy here. These were often ‘second sons’ who were members of the aristocracy but, due to British primogeniture laws (land and titles went to the first-born sons to maintain the overall position of the aristocracy in society), who would not be inheriting titles and estates. Additionally, there were refugees from the English Civil War (1642-1651). While the Northern colonies were (at first) populated largely by people who would end up on the Parliamentarian side of the civil war (the Puritans and other religious dissenters and, economically, many craftspeople and merchants), a stream of Royalist refugees from the civil war settled in the South, especially Virginia. The state still bears the nickname ‘Old Dominion’ and that plausibly relates back to Charles II recognizing its loyalty upon the restoration of the monarchy. Culturally, they brought with them their Anglicanism, refined aristocratic manners, commitment to social hierarchy, and sense of Cavalier (the name for the loyalist supporters of monarchy) romance. Finally, there were those with little or no connection to the traditional British aristocracy but who aspired to aristocratic status on this side of the Atlantic- it has always been a land of opportunity.

By the time of the Revolutionary War there was a well-established Southern planter aristocracy, especially in Virginia, but also in the Carolinas, comprised of ‘first families’ such as the Randolphs, Custises, Fitzhughs, Jeffersons, Lees, and Washingtons, among others. These families amassed large estates, designed and built elaborate and luxurious manor homes, maintained a social hierarchy, cultivated their manners, refined their sensibilities, and committed themselves to some genuine notions of noblessse oblige and public service.

Without a domestic peasantry to build their wealth and social position on, they first made some attempts to do so through indentured European labor but quickly settled on African slaves as their labor base, organized in the plantation system (indigenous slavery was also practiced). From an agricultural perspective, the aristocratic ideal was built on a base of large-scale farming of primarily cash crops, tobacco at first and later cotton.

The other agricultural ideal was also rooted in traditional English culture. It was of the independent yeoman farmer. The yeoman was not a peasant. They held free title to their own plot of land and through hard work and intelligence could maintain their economic independence. This ideal informed the ordinary farmers of the South (but also of the North to a considerable extent) and formed the backbone of what would become termed ‘Jeffersonian democracy.’ The yeoman was primarily a subsistence farmer, growing and making as many of the things they needed as possible – genuine material self-sufficiency was their way.

The yeoman was considered to be essential to the establishment of American republicanism by the Jeffersonians. Small farmers were held to be more virtuous than those engaged in commerce and finance, as were the rural as compared to the urban. They were independent (versus working for another) and hence could be capable of political deliberation in the public interest. They would jealousy defend their individual and local rights, preventing too much power from being centralized in the national government. As we look for ‘the faded republic,’ much of it is rooted here. It would also, ironically, form the ideological basis for continued westward expansion and imperialism because if the country was to be built on a body of virtuous and independent farmer-citizens, there had to be expanding amounts of cheap land for them to settle on.

Both of these ideals found their home primarily in the South. Much of the South’s flavor and mystery comes from it being a land of contradictions.

(Members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy at a memorial service).

The first lost cause

Hence, we see that Southern agriculture is in fact two distinct ideals and modes of agriculture. One was inexorably tied to the practice of slavery. The other was linked to the most egalitarian of visions which helped inform the early republic. How is it that two such distinct visions grew together to form the basis of Southern culture instead of ripping it apart as would seem natural purely from the perspectives of ideas?

Briefly, both were anti-capitalist and anti-industrialist. As the North, but the country as whole under Northern cultural influence, became more and more dominated by large financial interests, an industrializing economy and the urbanization that accompanied it, along with the wage system, both the aristocrat and the yeoman found themselves on the defensive.

Even before the American Civil War, an ideology developed to support the Southern way of life, and especially the peculiar institution that was at its core. In a typical irony of American history and civilization, the first serious criticisms of industrial capitalism were wed to a defense of slavery. Writers such as George Fitzhugh offered a sociological and moral critique of the industrial direction the country was headed in combined with a romanticized portrayal of docile, contented, and well-cared-for slaves. Whereas the Northern industrialist, he argued, need not care a wit for the impoverished hordes of immigrants housed in urban tenements comprising the industrial workforce, the Southern aristocrat’s ownership of his labor force meant that both his material self-interest and the bonds that developed through close social intercourse (possibly think of Jefferson and Sally Hemings here, but that probably isn’t the picture he was intending to convey) led him to ensure at least the basics of material comfort and security for his workers. So the story ran.

After the Civil War, defeated Southerners sought to defend their traditional agricultural ways in the face of industrial material and cultural colonization. To do so, they developed the ideology of what came to be termed the ‘Lost Cause.’ As they reinterpreted their history, culture, and values they drew on some of the elements we have noted. First and foremost, a preference for agriculture over industry and rural existence over urban. Also values of self-reliance and independence. The Civil War itself was reinterpreted as a cultural struggle over a way of life and ‘States Rights,’ not primarily slavery. On the other hand, it could be used to support white supremacy as a local custom. The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan could be presented as the contemporary embodiment of the chivalrous Cavalier ethos defending refined Southern culture and ‘white womanhood’ from both Northen imperialism coming from above and emancipated African-Americans from below. The Klan’s first Grand Wizard was literally a cavalier, a cavalryman. Nathan Bedford Forest revolutionized cavalry tactics in the Civil War and was a skilled and feared opponent.

There is a definite romanticism to the idea of a lost cause. In this case, Southern culture was held to be superior to that of the victors. Northerners were presented as crass materialists while Southerners were religious and spiritual folk. Northerners, during the war, had the population and the industrial might, but Southerners had virtue and martial genius. Southern men were gentlemen and Southern women were ladies or belles, while Northerners were confidence men and uncultivated females. The North was transactional, the South hospitable. The North crass, the South genteel and honorable. The North was cold and calculating, the South warm and sensual.

I’ll Take My Stand

When the Twelve Southerners set out to defend the Southern ‘Agrarian Tradition,’ the foregoing provides some essential background to make sense of that.

The Statement of Principles was written primarily by John Crowe Ransom1. The Statement opens by solidly contrasting “a Southern way of life” to “the American or prevailing way” and these are distilled down to “Agrarian versus Industrial” (p. xxxvii). He affirms that he is not talking political separation, but “how far shall the South surrender its moral, social, and economic autonomy to the victorious principles of Union” (p. xxxviii)? That is, it is a defense of cultural regionalism and localism.

In brief, as the South faces the question of industrializing head one, can one section of the country be allowed to go a different way or not? This is a question not of political federalism but what might be termed cultural federalism. Also, to what extent should Southern agrarians seek to create a national agrarian movement by aligning with, for example, Western agrarians?

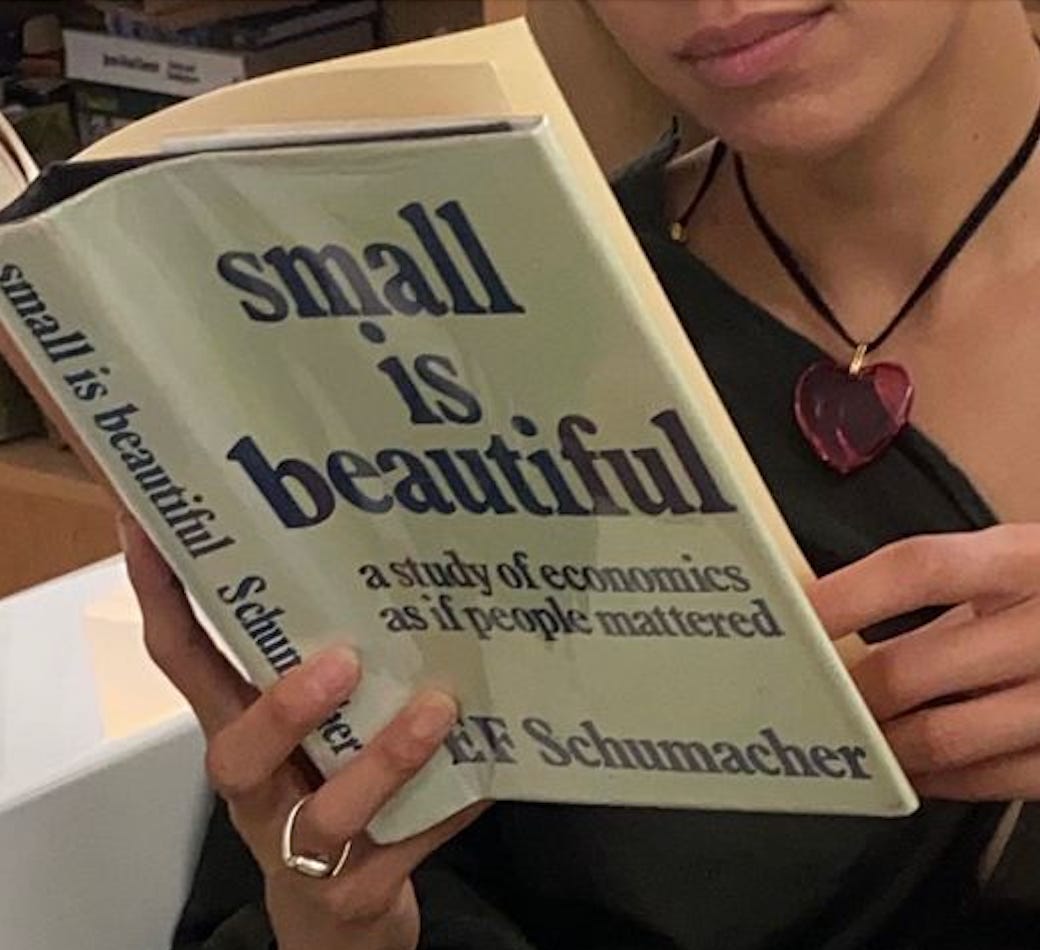

He defines “industrialism” as the decision made by a society to invest and subordinate its economic resources to the control of “the applied sciences” with the effect that this system has of enslaving “human energies” (p. xxxix). This system, he says, misconstrues the value of labor. On the one hand, while it promises release from labor through increased efficiency, it actually continually accelerates the burdensomeness and tempo of laboring. It also makes the mistake of thinking labor is an evil whereas in fact, from the agrarian point of view, “labor is one of the happy functions of human life” (pp. xl-xli).

Further, industrialism triggers cycles of overproduction, then unemployment, then growing inequality and instability. Further, to keep the whole contraption running, consumption must be stimulated beyond its natural bounds. Advertising is the magic invented to make this work “to persuade the consumers to want exactly what the applied sciences are able to furnish them with” which, he says, “is the great effort of a false economy of life to approve itself” (p. xlvi).

By contrast, he says, agrarianism is a genuine form of humanism. “Humanism, properly speaking,” he explains, “is not an abstract system, but a culture, the whole in which we live, act, think, and feel. It is a kind of imaginatively balanced life lived out in a definite social tradition” (p. xliv). The foremost unhuman effect of industrialism is to denature and diminish the role of religion in human life. “Religion is our submission to the general intention of a nature that is fairly inscrutable; it is the sense of our role as creatures within it”. This proper relationship to nature is fostered by agrarianism and undermined by industrialism. “But nature industrialized, transformed into cities and artificial habitations, manufactured into commodities, is no longer nature but a highly simplified picture of nature. We receive the illusion of having power over nature, and lose the sense of nature as something mysterious and contingent” (p. xlii).

With the distortion of the fundamental insights about our proper relationship to nature which undermines religion, the arts are also undermined as they too depend on maintaining a proper relationship to nature. Additionally, “such practices as manners, conversation, hospitality, sympathy, family life, romantic love” all suffer when we adopt the applied scientific view of nature and our role within it (p. xliii).

Against this he proposes maintaining an agricultural society where, though there will be industry and also non-agrarian professions, the majority of people will be kept engaged in agricultural work, the truer values attendant upon that will inform the regional culture, and the norms of farming will form the norms of the society as a whole because “the culture of the soil is the best and most sensitive of vocations” (p. xlvii).

This is about the last time in American civilization that the old Jeffersonian defense of the Yeoman received serious consideration and possibly had the opportunity to prevail, at least in certain sections of the country. But echoes of that tradition, and of the Southern Agrarians, can still be picked up in the thought of people like Wendell Berry.

Homegrown anti-industrialism

The tradition of thought running from Jeffersonian democracy to Jacksonian reform to the agrarian populism of William Jennings Bryan (and the political alliance of Southern and Western agrarians), to the Nashville Agrarians and beyond to inform parts of the 60s counterculture and 70s environmentalism, up to contemporary attempts to revive localism and various things ‘Trad,’ represents America’s homegrown intellectual and political tradition of anti-industrialism and anti-capitalism.

That last claim may strike you as odd – isn’t America capitalist through and through? However, I suggest that the South, at least as long as it was primarily agricultural, has been anti-capitalist. Not socialist, but anti-capitalist. Neither the ideal of the Gentry built on slavery nor the Yeoman ideal of independent small-holders, is compatible with industrial capitalism. And they knew it. And they fought a war over it. And they still didn’t give up. But they eventually lost that cause as well.

Our continuing respect for the ‘family farmer’ and the ‘small businessperson’ echoes this tradition and is archetypically American. However, the edge has been taken off of our ability to critique the actual enemies of small enterprise.

The American South fostered the only viable indigenous alternative to total large-scale homogenizing capitalist dominance of American life. There the republican ideal lived on, though sometimes obscured. The problem was that it was culturally (almost) inextricably bound up with racism and racial oppression.

Southern culture was the repository of white supremacy. It was also, and to an extent still is, the repository of American republicanism, localism, and individual liberty. Talk about contradictions.

When we, rightly, rejected those evils, we lacked the nuance and sophistication, by and large, to continue to affirm what was good and essential in the Southern way of life. As such, we largely lost contact with our organic critical tradition.

However, it’s still there, woven throughout American history, sometimes even serving as the dominant political tradition. We can reapproach the tradition of American agrarianism, Southern romanticism, localism, and the ideal of the independent, self-sufficient, and virtuous citizen. We have domestic resources to rethink our relation to nature, culture, and polity. In fact, America isn’t really America without it.

And by ‘Southern way of life’ I don’t just mean white Southern way of life. As at least some of the Southern Agrarians came to see, Robert Penn Warren chief among them, the values they affirmed in agrarianism entailed the civil rights and dignity of African-Americans, especially African-American farmers (though others were and would remain segregationists). In fact, culturally, I think a lot of what is distinctive in African-American culture has its roots in the South and in agrarianism. We will explore that more in future essays.

With the inheritance from its Gentry ideal, the South is still more mannerly, hospitable, sensitive, and romantic than most of America. From its Yeoman ideal it still values localism, self-reliance, dignity, individual freedom, religion, and public spiritedness. If it can recapture its critical edge, it may yet be able to pull off another renaissance.

Redneck, neo-Confederate, supreme. Oh, boy! With direct reference to the Twelve Southerners. Is there still room left for any of us to make any sort of ‘stand’? And are we anywhere near intelligent enough to sift the wheat from the chaff, the good from the evil? Our fate hangs in the balance.

Just before publishing this, I came across this nice passage in Paul Kingsnorth’s new book, Against the Machine: On the Unmaking of Humanity: “…what is needed is something more old-fashioned: a stance. A place to stand, based on a particular reality.” Seems the Twelve Southerners are as up-to-date as the current New York Times best-seller list.

References:

Twelve Southerners, I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition, Louisiana State University Press, 1977 (1930).

Wilson, Charles Reagan, The Southern Way of Life: Meanings of Culture & Civilization in the American South, The University of North Carolina Press, 2022, p. 146.

The ‘Civil’ (meaning ROMAN) war was actually a symbolic demonstration of separation … the ‘North’ from the ‘South’; the Capital from the Labor; the Head from the Body. Word etymology is important to these secret societies. The Civil War was a war on the human being and separated the head (thinking) from the body (labor) with the creation of ‘corporations’ as being ‘persons’. ‘Govern-ment’ = to control the mind. As you know, it’s always about separation… and then further distractions within those separations. But, the truth is always the truth and there are no sides to the truth. Whatever fabrications these forces and entities have created in this commercial realm (paper 2D realm), they will never be the truth.

LikeLike