by Paul Cudenec (who reads the article here)

It has become apparent to me that there are two aspects to political movements, organisations or institutions.

The horrible truth is that they all seem to have been taken over by the corrupt global mafia and turned into instruments for its control.

But, on the inside, there are always still the true believers who really do champion the values falsely trumpeted by the entity in question.

Because they know that they themselves are genuine, along, perhaps, with certain close colleagues, they cannot help but feel the whole endeavour to be authentic.

If they do become suspicious of the leadership and its real agenda, then they will probably think that their responsibility is not to desert the cause but to help put things right from within – and maybe they are right.

The same thing, I would say, is true of religions – I wrote recently about how Jacques Ellul separated the essence of Christian faith from the totally corrupted structures of the Church of all denominations. [1]

In all religions – in which category I obviously do not include satanic death-cults – there are people of good will with good hearts who are trying to do good in the world.

The most maligned religion today, at least in the “Western” world, is Islam.

Scholar Annemarie Schimmel (1922-2003) remarked back in 1994 that it was often depicted as “an anti-Christian, inhuman, primitive religion”. [2]

But she quotes Swedish Lutheran bishop, and student of Islam, Tor Andrae as insisting: “Like any movement in the realm of ideas, a religious faith has the same right to be judged according to its real and veritable intentions and not according to the way in which human weakness and meanness may have falsified and maimed its ideals”. [3]

Since then, of course, the demonisation of Islam has greatly increased, with decades of Zionist propaganda aimed at winning support for Israel’s genocidal assault on Muslim (and Christian) people.

This process has been amplified by indigenous European fears about the influx of large numbers of foreigners, which has been (deliberately) funnelled into specific animosity to Muslims.

We have also increasingly been hearing the line that Islam is a threat to “Western Civilization”, which we are told is based on “Judeo-Christian” values.

In truth, of course, Islam, Christianity and Judaism all have the same roots, although they have significantly diverged – with Christianity absorbing influence from traditional European beliefs and a similar thing happening to Islam in the Middle East, Iran, India and Africa.

Do those who believe in the existence of a “Judeo-Christian” civilization also believe in a corresponding “Judeo-Islamic” one?

This intertwining is made quite clear in Schimmel’s fascinating book Deciphering the Signs of God, which draws on a lifetime of academic research on the subject.

She explains that, from a Muslim perspective, Islam in fact has more in common with both Judaism and Christianity than either of these does with each other.

“The Koran describes the Muslim community as ummatan wusta (Sura 2:143), a ‘middle’ community, that is, a group of people who wander the middle path between extremes, just as the Prophet often appears as the one who avoided both Moses’ stern, unbending legalism and Jesus’ overflowing mildness; for, as the oft-quoted hadith says, ‘The best thing is the middle one'(Ahadith-i Mathnawi no 187)”. [4]

She notes that the Koran (Sura 2:125ff) speaks of the Kaaba, the Muslims’ sacred black cube at Mecca, as having been either built or restored by the Hebrew patriarch Abraham, before Muhammed claimed it for Islam in 630. [5]

The same proximity has also been noted by Jewish thinkers who reject the Zionist attacks on Islam.

According to one of America’s most prolific experts on Judaism, Rabbi Jacob Neusner (1932-2016): “No two religions among all the religions of the world, concurring on so much, have better prospects of understanding and conciliation than Islam and Judaism”. [6]

Professor Yakov Rabkin of the University of Montreal writes: “Judaic jurists viewed Islam as a strict monotheism, free from idolatrous deviations, and affirmed that Muslim hearts are directed towards Heaven…

“Consequently, according to Jewish law, Jews may enter mosques, while they are forbidden to approach idolatrous houses of prayer [churches]”. [7]

“Conceptual and often terminological affinities link Judaism and Islam… The Qur’an has a sacred status within Judaism”. [8]

As far as the links to Christianity are concerned, Jesus is of course regarded as an important prophet by the Islamic religion, though not as the son of God.

Schimmel says that the 13th century Sufi Muslim poet Rumi (depicted below) “compares the birth of the truly spiritual parts of the human being to the birth of Jesus from the Virgin Mary: only when the birth pangs – suffering and afflictions – come and are overcome in living faith can this ‘Jesus’ be born to the human soul”. [9]

She adds that the Koran does not refer to many women in its sacred history “but pride of place belongs to Maryam, the only one mentioned by name and extolled as the virgin mother of Jesus”. [10]

I do not think many Christians would have a problem with the Islamic view that “greed, ire, envy, voracity, tendency to bloodshed and many more negative trends make the human being forget his heavenly origin, his connection with the world of spirit”. [11]

As someone who has always felt deeply uneasy about the Christian concept of original sin, “inherited from generation to generation through the very act of procreation”, [12] I was pleased to learn that it is not present in Islam.

It also seems that even though Allah’s will is regarded as higher than any human will, this does not mean, according to Fazlur Rahma, that we have to do with a “watching, frowning and punishing God nor a chief Judge, but a unitary and purposive will creative of order in the universe'”. [13]

I like the holistic aspect to Islam, “the feeling that everything is bound in secret connection – stars and days, fragrances and colours”. [14]

Schimmel writes: “According to the Muslims’ understanding, not only the words and ayat [signs/verses] but also the entire fabric of the Koran, the interweaving of words, sound and meaning, are part and parcel of the Koran”. [15]

As long-term readers will know, my personal interest in Islam has focused on the mystical Sufi tradition.

Schimmel reminds me of why I feel this affinity when she states that for early Sufis, “government was generally equated to evil and corruption”. [16]

“Medieval history knows of a number of Sufi rebels against the government (Qadi Badruddin of Simavna (d. 1414) in Ottoman Turkey, Shah ‘Inayat of Jhok in Sind in the early eighteenth century) or, like Shariatullah, against the rich landlords in Bengal”. [17]

I also like the idea that we can approach the truth “through tahqiq, direct experience, not through taqlid, dogmatic imitation” [18] and that a spiritual seeker “may grow into a true ‘man of light’, whose heart is an unstained mirror to reflect the Divine light and reveal it to others”. [19]

In order to have remained within the Islamic tradition, Sufis have had to walk a thin line on the question of God’s transcendence – a thin line over a grey area, in fact.

Mainstream Islam is centred on the total transcendence which I identify as a problem in my book Our Sacred World and yet, points out Schimmel, the Koran also refers to the One as being closer to mankind than their jugular vein (Sura 50:16). [20]

And Sufis, for their part, have gradually moved from the idea of annihilation in Allah to annihilation in Muhammed, since the divine essence “remains forever beyond human striving”. [21]

Despite such nuances, the theological divide is a very real one and has been the cause of much dispute over the centuries, Schimmel says.

“The tension between the two major aspects of Islam – the normative-legalistic and the popular, mystically tinged one – forms a constant theme in Islamic cultural history”. [22]

“Those whom the Sufis, and following them many orientalists, regard as the famous martyrs are usually considered heretics by the orthodox”. [23]

Music and dance play an important role in the Sufi way, both theoretically and practically.

Schimmel says of Rumi: “When he frequently compares himself to a reed flute which sings only when the lips of his beloved touch it, he has expressed well the secret of inspiration”. [24]

“Rumi had sung most of his poetry while listening to music and whirling around his axis, and to him the whole universe appeared as caught in a dance around the central sun, under whose influence the disparate atoms are mysteriously bound into a harmonious whole”. [25]

“Dance, especially the whirling dance, goes together with ecstasy, that state in which the seeker seems to be leaving the earthly centre of gravity to enter into another spiritual centre’s attracting power, as though he were joining the angelic hosts or the blessed souls”. [26]

“The mystic might feel the bliss of unification when he had lost himself completely in the circling movement, and thus dance can be seen as ‘a ladder to heaven’ that leads to the true goal, to unification.

“But as this goal contradicts the sober approach of normative theologians, who never ceased to emphasize God’s Total Otherness and who saw the only way to draw closer to Him in obedience to His commands and revealed law, their aversion to music and dance is understandable”. [27]

The form of Islam which rejects Sufism is based on “nomos” – essentially law and order – rather than on vitality and organicity.

Schimmel explains: “As the normative theologians disliked the ecstatic dance as a means to ‘union’, they also objected to a terminology in which ‘love’ was the central concept.

“Nomos-oriented as they were, they sensed the danger of eros-oriented forms of religion which might weaken the structure of the House of Islam.

“They could interpret ‘love’ merely as ‘love of obedience’ but not as an independent way and goal for Muslims, and expressions like ‘union’ with the One who is far beyond description and whom neither eyes could reach nor hands touch seemed an absurdity, indeed impiety, to them”. [28]

Pitted against the mystics’ inner joy – “an integral part of true Sufi life” [29] – we see “the attitude of the hardline religious orthodoxy, of lawyer-divines or religious teachers” [30] and the Koran’s “numerous legal instructions”. [31]

Schimmel writes: “The Law promises, perhaps even guarantees, the human being’s posthumous salvation, while in the mystical trends the tendency is to ‘touch’ the Divine here and now, to reach not so much a blessed life in the Hereafter (which is only a kind of continuation of the present state) but rather the immediate experience of Love”. [32]

“Love is certainly not an attitude which one expects to find on the general map of Islam, and the use of the term and the concept of love of God, or reciprocal love between God and humans, was sharply objected to by the normative theologians: love could only be love of God’s commands, that is, strict obedience”. [33]

This harsh and authoritarian aspect of Islam must in part reflect its Abrahamic roots, in the same way as the “puritans” of Christian Protestantism were much inspired by the Old Testament.

But, argues Schimmel, it can also be traced back to the fact that “Islam was preached first and developed later in cities: in the beginning in the mercantile city of Mecca, later in the capitals of the expanding empire. ‘City’ is always connected with order, organization and intellectual pursuits”. [34]

The religion’s subsequent “pollution” by supposedly alien elements is in fact its adaptation to the beliefs and values of the peoples it converted.

If the popular and mystic current sometimes looks like a completely different religion to Islam, it is perhaps because it represents a green shoot of ancient sacred gnosis sprouting up through the cracks of the legalistic Abrahamic stone.

Schimmel says: “The Sufis have been and still are harshly criticised for introducing foreign, ‘pagan’ customs into Islam and polluting the pure, simple teachings of the Koran and the Prophet by adopting gnostic, ‘thoroughly un-Islamic’ ideas”. [35]

“A large variety of popular forms grew, especially due to Sufism with its emphasis, mainly on the folk level, on the veneration of saints.

“This trend often appeared to the normative believers as mere idol-worship, as a deviation from the clear order to strict monotheism which had to be defended against such encroachments of foreign elements, which, however, seemed to satisfy the spiritual needs of millions of people better than legal prescriptions and abstract scholastic formulas”. [36]

Satisfying human beings’ spiritual needs is obviously a very bad thing indeed, as is standing in the way of any kind of modernisation – physical, social or religious.

Schimmel explains: “Many Western observers considered Sufism the greatest barrier to a modern development in Islam.

“Muslim thinkers like Iqbal joined them, claiming that molla-ism and pir-ism were the greatest obstacles to truly Islamic modern life, and that the influence of ‘pantheistic’ ideas in the wake of Ibn ‘Arabi’s (pictured below) teachings and the ambiguous symbolism of – mainly Persian – poetry and the decadence that was its result (or so he thought) were ‘more dangerous for Islam than the hordes of Attila and Genghis Khan'”. [37]

More conservative-minded Muslims, she says, were and are also “blamed, especially in modern times, as those who resist modernization and adaptation to the changing values and customs of the time because they see the dangers in breaking away from the sacred tradition”. [38]

As I have often explained, the Empire needs to destroy any belief systems or ways of life that risk impeding its ever-expanding global exploitation and control. [39]

I reveal some of the history of this in my article on the Invisible College, which was the precursor of the Royal Society in 17th century Britain, [40] and in that on Thomas Hobbes and Leviathan’s Law. [41]

In both instances, we find strong connections between the “rational” and “scientific” modern ways of thinking and the Judaic religious tradition.

There is also a longstanding practical Jewish involvement in world commerce, industry and finance which reinforces the relevance of such a connection.

As the Empire expanded, the subjugation of more and more peoples would necessarily have to involve the continuation of the same process which began in Europe – the erasure of any indigenous beliefs that were incompatible with industrial imperialism.

I presented evidence of this in my 2014 book The Stifled Soul of Humankind, when I relayed René Guénon’s account of the British Empire’s attempted use of the Protestant mindset to control the population of India.

He describes how in the first half of the 19th century, Rām Mohun Roy (pictured) founded the Brahma-Samaj or “Hindu Reformed Church”, complete with Protestant-style services, at the behest of Anglican missionaries.

Says Guénon: “It marked in fact a first attempt to convert Brahmanism into a religion in the Western sense, and at the same time it showed that its promoters wished to make of their venture a religion animated by the self-same tendencies that characterize Protestantism.

“As was to be expected, this ‘reforming’ movement was warmly encouraged and supported by the British government and by British missionary societies in India; but it was too openly anti-traditional and too flatly opposed to the Hindu spirit to succeed, and people plainly took it for what it really was, an instrument of foreign domination”. [42]

In that same book I look at the theological propaganda served up in 1957 by Oxford University professor Robin Zaehner.

I note his strangely aggressive reaction to Aldous Huxley’s statement that in industrial societies most of us endure such monotonous and limited lives that “the urge to escape, the long to transcend themselves for a few moments” is a natural response. [43]

Zaehner (pictured) insists that Huxley’s reaction is one of a neurotic intellectual, that the “healthy-minded” majority have no problem at all living in an industrial world and that “there is a definite connexion between nature mysticism and lunacy”. [44]

He declares that some Sufi thinkers are “purely paranoiac cases” [45] and he says that one passage from the Hindu Upanishads “seems to be based on a praeternatural experience akin to acute mania”. [46]

Zaehner continues, with striking arrogance: “The mere fact that the Upanishads are revered as a sacred book by hundreds of millions should not blind us to the fact they are the efforts of relatively primitive men to discover an adequate philosophy of the universe”. [47]

The core of his concerns is, I think, revealed when he complains: “On the premisses of the Māndūkya Upanishad there can be no humility or sense of awe in the face of an Absolute Being who alone really exists and is distinct from man: there can be no sense of nullity or of unworthiness”. [48]

And he remarks, rather tellingly: “There comes a point in most lives when one tires of the ceaseless responsibility of having to act and choose, and one longs for a higher power to take over the direction of one’s life even if the higher power is only the army or a party organization”. [49]

I put Zaehner’s worldview into a pragmatic context when I reveal that he worked for MI6 and, alongside the CIA, planned the coup which brought down the elected government of Iran in 1953, restoring the Shah and handing nationalised oil production back over to the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, later to be known as BP. [50]

Schimmel reveals a similar phenomenon in her book when she describes attempts to remove any mystic elements from Islam, to flatten it into conformity with “modern” thinking.

“This process of ‘demythologization’ is very visible, for example in a translation-cum-commentary of the Koran issued by the Ahmadiyya (at a time when this movement was still considered to be part of the Islamic community).

“In the exegesis of the powerful eschatological description in Sura 81, ‘And when the wild animals are gathered’, the commentator saw a mention of the zoos in which animals would live peacefully together in later ages”. [51]

The Kharchoufa website tells us that the general aim of Islamic reform movements is to “reconcile faith with modernity” and address “scientific advancement”.

“Important figures like Sir Sayyid Ahmed Khan and Muhammad Abduh shaped Islamic modernism. They suggested reinterpreting Islamic texts for today’s social, political, and scientific world”. [52]

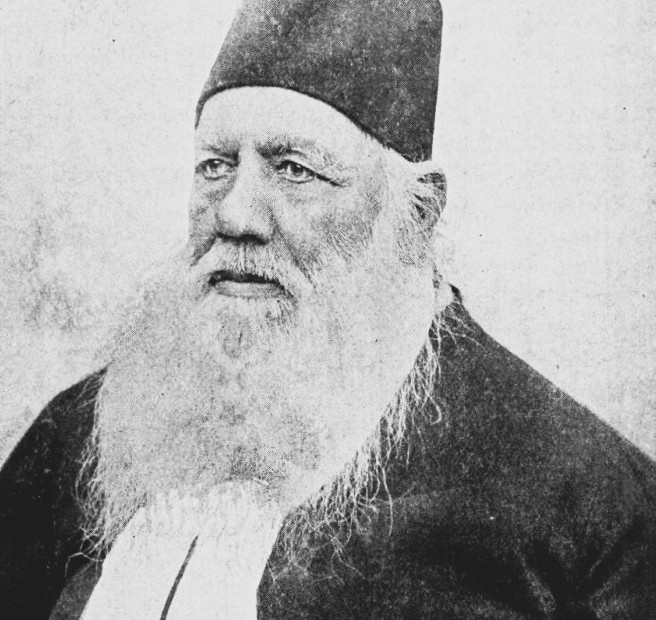

Schimmel writes in her book about Sir Sayyid/Syed (1817-1898), the reformer of Indian Islam.

She says: “Sir Sayyid went far beyond the limits of what had hitherto been done in ‘interpreting’ the Koran. He tried to do away with all non-scientific concepts in the Book, such as djinns (which were turned into microbes)”. [53]

Sir Sayyid (pictured) was, as his title alone screams out, a loyal servant of the Empire.

Says Wikipedia: “His father was involved in regional insurrections aided and led by the East India Company, which had replaced the power traditionally held by the Mughal state, reducing its monarch to a figurehead”. [54]

In 1838 Sir Sayyid entered the service of the East India Company and “supported the East India Company during the 1857 uprising”, it says.

Following understandable criticism from other Indians, he promptly brought out a pamphlet entitled The Causes of the Indian Revolt (Asbab-e-Baghawat-e-Hind), which appeared to criticise the Empire but was treated by British officials as “a sincere and friendly report”.

He then “criticised the influence of traditional dogma and religious orthodoxy, which had made most Indian Muslims suspicious of British influences” and “intensified his work to promote co-operation with British authorities, promoting loyalty to the Empire amongst Indian Muslims”.

Sir Sayyid also formed the Scientific Society of Aligarh, “modelling it after the Royal Society”.

The Invisible College goes to India!

“The Society held annual conferences, disbursed funds for educational causes and regularly published a journal on scientific subjects in English and Urdu.

“Sir Syed felt that the socio-economic future of Muslims was threatened by their orthodox aversions to modern science and technology.

“He published many writings promoting liberal, rational interpretations of Islamic scriptures, struggling to find rational interpretations for jinn, angels, and miracles of the prophets”.

He also founded the Anglo-Oriental College – “modelled on Cambridge and Oxford imparting modern education to Indians” – and, of course, his “pioneering work received support from the British”.

In 1888, Sir Sayyid established the United Patriotic Association to “promote political co-operation with the British” and was knighted by the British government “for his loyalty to the British crown, through his membership of the Imperial Legislative Council”.

Part of his role was the pacification of the Muslim section of the Indian population on behalf of the Empire, penning propaganda which “highlighted the bravery of those Muslims who stood by the British” and made “a clear distinction between jihad and rebellion”.

But another element of his efforts will come as no surprise to anyone who is aware of what really lay behind the “British” Empire and today lies behind the global Occupation.

This involved his argument, in his tafsir (exegesis) of the Koran, regarding riba – usury.

He argued that this practice should henceforth be regarded as acceptable by Muslims in a commercial context because interest-bearing loans were good for “trade, national welfare and prosperity”! [55]

Over the course of hundreds of years, all the world’s institutions, including religions, have progressively been targeted for infiltration, corruption and manipulation by the global mafia, aka ZIM.

Everywhere, their aim is the same – to destroy our cultures and our freedom and to turn us into their slaves. Leviathan’s Law is all about order and obedience, servility and “science”, conformity and control.

Our hearts have been caged by their industrial work camp and we have lost all that we once valued most. But they are still beating, and beat again in each new child born to the world.

As I said at the start of this piece, the Empire controls the world’s structures but not all the living people within them. They cannot rely on their permanent obedience.

We are human beings, after all, and nobody could knowingly welcome a toxic future of degraded slavery for their children and their children’s children.

Human beings naturally want to dance and sing; we yearn for joy, ecstasy and love. If we follow our wild hearts and whirl fast enough in ecstatic fury at our wretched imprisonment, we can burst open the cage door and finally fly free.

[1] Paul Cudenec, ‘Christianity and the forces of evil’, https://winteroak.org.uk/2025/10/01/christianity-and-the-forces-of-evil/

[2] Annemarie Schimmel, Deciphering the Signs of God: A Phenomenological Approach to Islam (Albany: State University of New York, 1994), p. x. Thanks to my friend Ibraar for the recommendation. All subsequent page references are to this work, unless otherwise stated.

[3] p. viii.

[4] p. 202.

[5] p. 57.

[6] Jacob Neusner et al, Judaism and Islam in Practice: A Sourcebook (London: Routledge, 2000), p. 234, cit. Yakov Rabkin, Israel in Palestine: Jewish Rejection of Zionism (Atlanta: Aspect Editions, 2025), p. 7.

[7] Rabkin, p. 8.

[8] Ibid.

[9] p. 184.

[10] p. 199.

[11] p. 179.

[12] p. 99.

[13] Fazlur Rahman (1966) Islam, p. 40, cit. p. 222.

[14] p. 15.

[15] p. 165.

[16] p. 212.

[17] p. 213.

[18] p. 165.

[19] p. 13.

[20] p. 223.

[21] p. 190.

[22] pp. xiii-xiv.

[23] p. 196.

[24] p. 118.

[25] p. 104.

[26] Ibid.

[27] pp. 104-05.

[28] p. 105.

[29] p. 252.

[30] p. 248.

[31] p. 160.

[32] pp. 249-50.

[33] p. 251.

[34] p. 255.

[35] p. 213.

[36] p. 245.

[37] p. 213. Iqbal, Foreword to Muraqqa-i Chughtay, a collection of paintings by Abdur Rahman Chughtay.

[38] p. 186.

[39] See Paul Cudenec, ‘Our impossible resistance will prevail!’, https://winteroak.org.uk/2025/12/05/our-impossible-resistance-will-prevail/

[40] Paul Cudenec, ‘The Invisible College and the plan for our enslavement’, https://winteroak.org.uk/2025/08/11/the-invisible-college-and-the-plan-for-our-enslavement/

[41] Paul Cudenec, ‘Leviathan’s Law and the occupation of our lands’, https://winteroak.org.uk/2025/11/04/leviathans-law-and-the-occupation-of-our-lands/

[42] René Guénon, Introduction to the Study of the Hindu Doctrines, trans. by Marco Pallis, (Hillsdale, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2004) p. 232, cit. Paul Cudenec, The Stifled Soul of Humankind (2014), p. 66, https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/the-stifled-soul-of-humankind-w.pdf

[43] Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception, p. 49, cit. R.C. Zaehner, Mysticism Sacred and Profane: An Inquiry Into some Varieties of Praeternatural Experience (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), p. 15.

[44] Zaehner, p. 51.

[45] Zaehner, p. 185.

[46] Zaehner, p. 186.

[47] Zaehner, p. 117.

[48] Zaehner, p. 158.

[49] Zaehner, p. 142.

[50] See Robert Fisk, Another Fine Mess,

https://web.archive.org/web/20130419032317/http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article4588.htm

[51] p. 164.

[52] https://kharchoufa.com/en/reform-movements-in-islam-you-should-know-about/

[53] p. 163.

[54] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syed_Ahmad_Khan

[55] Ibid.

we are all searching for the perfect religion but the real key might just be the love of nature which can create a singular presence in each one of us, done without a control mechanism but attached to our own heart as we discover the glory of the outdoors without religion but our connection to our interpretation of God

LikeLike

Yes. A connection to the world around us and the cosmos beyond. Knowing that we are not just absurdly separate individuals with no belonging to a bigger whole.

LikeLike

Yes, well needed insights as to the ultimate incarnation of the “Rite of Spring”, the body electric and joy of life directed by we the people.

LikeLike