by Paul Cudenec (who reads the article here)

Max Weber, the subject of my last essay, was not alone in suspecting that certain religious beliefs – or the lack of them – had played a key role in shaping modern industrial society.

Indeed, a century before Weber wrote about “die Entzauberung der Welt” – the disenchantment of the world – German playwright and poet Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) described “die Entgöttung der Natur” – the “disgodding” of nature. [1]

While people were still paying lip service to their God, they were not seeing and respecting His presence in the living world.

Divinity was no longer regarded as existing here on earth, amongst us and within us, but uniquely in a separate realm to which we could only have access via the intermediaries of organised religion.

As Marshall Sahlins notes: “The essential change was the translation of divinity from an immanent presence in human activity to a transcendental ‘other world’ of its own reality, leaving the earth alone to humans, now free to create their own institutions by their own means and lights”. [2]

Morris Berman writes that it is very difficult to form a reliable impression of the consciousness of premodern society and to know to what extent this was influenced by animism, the knowledge of spirit in nature.

He continues: “One thing that is certain about the history of Western consciousness, however, is that the world has, since roughly 2000 BC, been progressively disenchanted, or ‘disgodded’.

“Whether animism has any validity or not, there is no doubting its gradual elimination from Western thought.

“For reasons that remain obscure, two cultures in particular, the Jewish and the Greek, were responsible for the beginnings of this development.

“Although Judaism did possess a strong gnostic heritage (the cabbala being its only survivor), the official rabbinical (later, talmudic) tradition was based precisely on the rooting out of animistic beliefs”. [3]

He says the very fact that Yahweh insisted on his people worshipping no gods other than him is proof that pagan beliefs in other deities were still alive in that part of the world.

John Lamb Lash makes exactly the same point when he writes about “Pagan divinities who pervade nature, manifesting in all manner of creatures, in clouds and rivers and trees, even in rocks”.

He notes: “Monotheism will tolerate none of these sensuous immanent powers. It makes the earth void of divinity, its inhabitants subject to an off-planet landlord”. [4]

In what Lash terms “the nature-hating basis of monotheism”, [5] Berman sees “the first glimmerings of what I have called nonparticipatory consciousness: knowledge is acquired by recognising the distance between ourselves and nature”. [6]

He adds: “Ecstatic merger with nature is judged not merely as ignorance, but as idolatry”. [7]

“Matter, as well as the earth, is effectively dead; and God is not a world soul, but a world director”. [8]

Alain Daniélou warns: “The principle itself cannot be personified”. [9]

“The danger of monotheism is that it results in the reduction of the human being and an appropriation of God for the service of a ‘chosen’ race.

“It is the opposite of a real religion, for it serves as a pretext for the subordination of the divine work to human ambitions”. [10]

For me, as a believer in the divine One, the key issue is the separation of that divine from the natural world and the way this total transcendence is also used to cut human beings off from our belonging to nature.

Daniélou regards this as emerging from nomadic cultures which “have no real contact with the world of nature”. [11]

He explains: “The monotheist simplification seems to have emerged from a nomadic religious concept, amongst peoples who were seeking to assert themselves, to justify their occupation of territories and their conquests.

“God is imagined in the image of man. He is reduced to the role of a guide who accompanies the tribe in its migrations and gives personal instructions to its chief.

“He is only interested in human beings and, amongst them, only in the group of the ‘chosen’.

“He becomes an easy pretext for conquest, for genocide, for the destruction of the natural order, as we can observe throughout the course of history”. [12]

Judaic influence seems particularly significant in this respect, not least via Christianity – even though, as Daniélou remarks, the latter faith seems to have initially been “a message of liberation and revolt against a Judaism which had become monotheistic, dry, ritualistic, puritan, Pharisee and inhuman”. [13]

Sahlins cites the Dutch orientalist Henri Frankfort’s reference to the “austere transcendentalism” of the ancient Hebrew God and his statement that “the absolute transcendence of God is the foundation of Hebrew religious thought”. [14]

Lash, for his part, refers to a 2001 collection of essays entitled Deep Ecology and World Religions published by the State University of New York Press.

He remarks: “Most of the contributors manage to squeeze ecological values from the existing traditions, but Eric Katz, writing on ‘Judaism and Deep Ecology’, confesses ‘profound misgivings that traditional Judaism can be understood as an ally of deep ecology’”. [15]

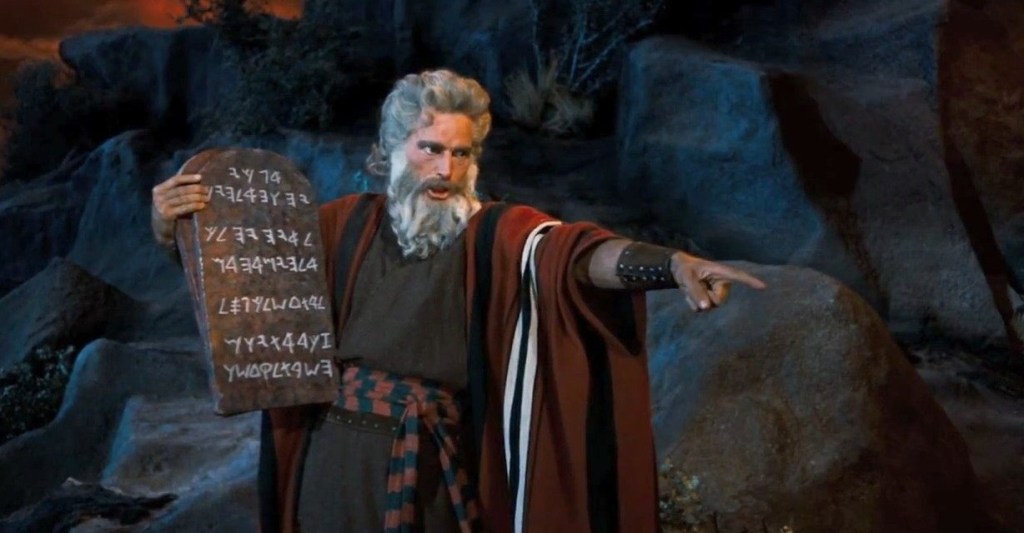

Lash argues: “The biblical directive script is about psychic distancing from nature and alienation from generic humanness.

“This is contrary to the universal form of indigenous narrative that relates how ‘the people’ emerge from nature, but remain grounded there, reflected in their habitat where they learn to live by observing organic laws and interacting with other species.

“The ancient Jews did not discover conscience, the power to choose what is right, they merely introduced a set of rules purporting to dictate what is right…

“The rules for living for the ancient Hebrews came from outside the natural world in the form of a model morality dictated by a distant superterrestrial deity”. [16]

“Rooted in nature, humanity does not need preset behavioral rules to follow, but uprooted from nature we are compelled to replicate what we’re missing”. [17]

This strikes me as a crucial point. Because we are part of a greater living organism, we naturally contain within us the patterns of its thinking, its values, its telos.

We have an inner moral compass in our hearts that we can choose to access and to heed.

Not only do we not need external rules to follow, but these rules – manipulated by those who have declared themselves their upholders so as to advance their own control agenda – prevent us from following our own inner moral compass, both individually and collectively.

The inversion of right and wrong by authoritarian organised religions and associated states defines these dogmatic and controlling rules as representing nothing less than divine will and thereby relegates natural law to the status of heresy.

It is this tension between what we know to be right and true and what self-appointed “authorities” tell us we must think and do that is the greatest cause of human unhappiness.

We find ourselves living in societies governed by rules which conflict with our innermost sense of meaning, of love for each other, for life and the cosmos.

We are forced to submit to a code of conduct and thought that is not our own, not that of nature. We are thus not free to think and act authentically; we are not free to be who we are meant to be.

[1] Morris Berman, The Reenchantment of the World (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1981), p. 69.

[2] Marshall Sahlins, with the assistance of Frederick B. Henry Jr, The New Science of the Enchanted Universe: An Anthropology of Most of Humanity (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2022), p. 2.

[3] Berman, p. 70.

[4] John Lamb Lash, Not In His Image: Gnostic Vision, Sacred Ecology, and the Future of Belief (White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green, 2006), pdf version, p. 221.

[5] Lash, p. 19.

[6] Berman, p. 71.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Berman, pp. 110.

[9] Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos: La Religion de la Nature et de l’Eros de la préhistoire à l’avenir (Paris: Fayard, 1979), p. 285. Translations are my own.

[10] Daniélou, p. 19.

[11] Daniélou, p. 18.

[12] Daniélou, p. 285.

[13] Daniélou, p. 287.

[14] Henri Frankfort et al, eds, The Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man: An Essay on Speculative Thought in the Ancient Near East (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1946/1977), p. 343, cit. Sahlins, p. 4.

[15] Roger S. Gottlieb and Barnell, David Landis, eds, Deep Ecology and World Religions (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2001), p. 154, cit. Lash, p. 127.

[16] Lash, p. 228.

[17] Lash, p. 229.

God is all around us, within us, part of us and apart from us. The Divine is ineffable, incomprehensible and non-malleable by the diktats of man’s laws. As an abstract, the Divine is nonsense, thus organised religion gains control, mandates behaviours and is, therefore, godless. Good article, made me think hard. Also, great references, some great minds have been led away from God by their own hubris, I suppose.

LikeLike