by W.D. James

Each of us, whether we fully realize it or not, are probably in a battle with Nihilism.

Nihilism is the philosophical stance that holds that life is inherently meaningless and that objective values don’t exist.

There have been people who consciously held this belief (the rationale for why they continued to get out of bed in the morning eludes me). However, I don’t think most people who end up being nihilistic mean to. They’re sort of accidental nihilists. It’s like with dog poop: very few people intentionally step into it, but if you’re not paying good attention, it happens. Sometimes entire ages and civilizations end up in that position.

In these instances, it’s more likely that the people involved saw something they thought was evil (by definition, can’t have been a nihilist at that point) and decided to tear down what they thought was supporting that evil.

In the modern world (the age of so called ‘revolutions’), the evil that many people saw was tyranny, or domination, or anything else they saw as inhibiting or diminishing the positive good of freedom (definitely not a nihilist: can identify evils and goods). However, collectively, we’ve been a bit better at tearing down what we thought was bad than building up what we thought was good.

Further, we’ve been better logicians than ethicists. We moderns can be darn consistent when it comes down to it. What we don’t always see are the ethical and lived consequences that come from applying an idea or program consistently. For instance, one of the ‘fathers of anarchism,’ Mikhail Bakunin, once reasoned like this: “If God exists, man is a slave; now, man can and must be free; then, God does not exist. I defy anyone whomsoever to avoid this circle.” He was trying to be thorough when he proclaimed “No Gods, No Masters” because the masters did in fact often appeal to God (or the Church, or Nature, or some metaphysical principle) when justifying their authority. Instead of arguing that they were misapplying that principle to serve their own interest, he decided it would be good to have the job done once and for all and throw out transcendent principles as well. What he seems to have missed is that if you throw out all the transcendent things power might appeal to in order to justify its authority, you probably also undercut your ability to defend the goodness of freedom or the badness of tyranny. Bad? Says who; you Mikhail?

The ‘Death of God’ (that includes God, but also any absolute transcendent principle: the Good, the True, the Beautiful, Nature, etc.) was called for by Bakunin (and many iconoclasts in the service of liberty) and lamented by Nietzsche. He, at least, realized where that leaves us.

I like to refer to the sort of freedom sought by Bakunin as ‘free freedom’ to emphasize its metaphysical depth. I’m not sure Bakunin actually saw this accurately, but he did have a point. Let’s say we could discern some objective moral standard, whatever it might be, for these purposes it doesn’t really matter what it is. If I recognize that something is good or that some other thing is bad (really good or bad, not just good or bad because I said so or because I happened to like the one or dislike the other) I am not free free. I have recognized the moral authority of something independent of and above my will. In a case like that, it’s awfully hard to go ‘I know X is bad, but I really think I should do X all I can’ and be at all consistent.

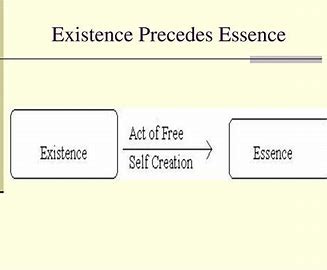

Jean-Paul Sartre was a philosopher who did get this and, at least in his earlier days, sided with free freedom. In a nice little metaphysical phrase, he aptly summed up this philosophical position: “existence precedes essence,” he said.

What does that mean? Traditionally, the essence of a thing was understood to be what made that thing the sort of thing it was. The essence transcended the particular thing. For instance, what makes me, you, and the guy over there ‘humans’ is that we all share in a thing than transcends each of us: humanness or human nature. Also, traditionally, philosophers figured that essences preceded the existence of particular things: human nature existed before me, you, and that guy. Hence, when we come into the world, there is a transcendent guide we have access to (which can help us understand what a good human and a bad human are).

Sartre is saying ‘No’ to that. With “existence precedes essence” he is saying that me, you and that guy come into the world (“thrown” he says) and there is no transcendent anything to guide us. Each and every one of us, all on our lonesome, get to (have to, he says) decide what ‘human’ will mean and we affirm our own unique take on that through our decisions. We will become the sort of human we want to be and that, for us, will define what human is. This has all sorts of technical problems which Sartre did, later, try to address.

The biggest problem is that whatever I decide I’d like humans, or at least this human, to be is really arbitrary, ethically speaking. I decide to join the French resistance and fight Nazis. I decide to become a Nazi. Well, I was free to do either and neither I nor you have a transcendent moral basis to decide which is better.

All truths are relative! (Except, of course, the truth that all truths are relative, that one is really truly true).

We can see something like this operating at a popular level in modern relativism. Sartre knowingly, and most of us more or less unknowingly (without having thought through the consequences anyway) have opted for free freedom. A discerning person will also see here the roots of transhumanism and transsexualism (I, not nature or even my own body, decide!). The main problem is we cannot, at that point, even defend the value of freedom (or any other real values).

And the cost of that is nihilism. When we demand freedom from metaphysical constraint, we lose objective meaning and value as part of the bargain.

Opposed to this nihilism-inducing free freedom I would like to oppose what I’ll term ‘meaningful freedom.’

A proponent of meaningful freedom will first and foremost seek out a basis for avoiding nihilism. You can’t just conjure that up and in our post-modern world it will likely take some real thinking.

Let’s say we manage to come up with a source of objective value we can believe in. We could call it God, Brahmin, the Tao, the Logos, Nature, the Good, or whatever. Now, I can know what freedom is for. If X is good, I very consistently would like and value being free to do X and anyone who tried to bind my freedom from doing X would be bad in a way that I can morally explain. That is, freedom does much better in a world that makes moral sense (both the exercise of freedom and the political pursuit of it).

I know it’s hard to get the image of Noam Chomsky as a cringing old man sitting in front of his computer camera during COVID calling for unvaxxed people to be put in concentration camps (that is a slight exaggeration) out of one’s mind, but there was a more principled Chomsky once upon a time. In his famous debate with Michel Foucault, the battle between free freedom and meaningful freedom was exactly what they were debating (but not in those terms, those are mine).

Here is a brief excerpt:

Both thinkers were known as centering their thought on freedom. Chomsky knows the threat of nihilism and wants to insist we need some notion of Human Nature which will undergird the idea that freedom is a positive value for creatures like us if we’re going to meaningfully defend it.

Foucault, willing to pay the price of nihilism, wants free freedom. He says whatever conception of Human Nature we come up with will be an effect of power and domination, so it is best to just remain open on that issue.

I guess if I believed in free freedom I would certainly use that freedom to never get out of bed.

So, what if we see the nihilistic problem with free freedom, but haven’t yet found a source of objective value to undergird a commitment to meaning? I suspect that is almost the default position of most of us in our current time.

Given the above analysis, I think we can see why meaningful freedom would be objectively preferable to free freedom. Hence, we would be in a position of making a choice (the sort of choice Sartre said we had to make). He said we had to opt for affirming free freedom (or else we would be guilty of “bad faith,” the great evil of Sartrean existentialism…but not really evil if I choose it?).

I see no compelling reason for that. I claim the liberty to avoid that conclusion. If, however, I do not yet possess convincing knowledge of Human Nature (or whatever transcendent normative standard I would use to guide the good use of my freedom) I cannot just will it were so.

What I can opt to do though is to seek for such a basis. I can refuse nihilism and go on a (philosophical) quest.

I call this decision the ‘option for meaningful freedom.’

And you know what? That quest itself provides some meaning for my decisions and life.

By exercising that option, I win in the battle with nihilism whether my quest is ever fulfilled or not.

This essay was first published as a part of Nevermore Media’s Against the Rising Tide of Nihilism series.

In emails between Chomsky and Epstein regarding Epstein’s public relations/image problems, Chomsky suggests that Epstein should (paraphrase) “Wait it out, let it blow over, and go on with what matters.”

It is incumbent upon Chomsky to provide a legitimate explanation of precisely the facts and details concerning the definition of “what matters” in the context of Chomsky’s personal relationship with the late, infamous sexual predator Jeffrey Epstein.

“Go on with WHAT matters, Noam Chomsky?” Technocracy? … Transhumanism? … Central bank digital currency slavery? Universal basic income? Nano-brain/neurowarfare, synthetic biology, directed energy weapons (See: Venezuela) etc. as described by DARPA-soaked neuroscientist Dr. James Giordano in Giordano’s absolutely horrifying public lectures?

LikeLike

Yes, we are due an explanation from Chomsky before he departs this mortal coil. Don’t suppose we will get one. Unless he cares to comment here? [sarcasm]

LikeLike

I respected Chomsky for his writings on anarchism, however after learning about his questionable friendship with Epstein he now appears rather hypocritical as Epstein represented the system that anarchist vehemently oppose as opposed to providing advice and moral support.

LikeLike

Yes. Chomsky’s overall reputation is very much in doubt – but that does not mean he wasn’t right on one or two points!

LikeLiked by 1 person