by Paul Cudenec (who reads the article here)

Grim events at the end of the Second World War have cast a certain shadow over the nation of Poland.

It was on its soil that stood Nazi concentration camps such as Auschwitz and Treblinka and Poles have sometimes been judged culpable in some ancillary way for the actions of the occupying Nazi regime.

But important light is shed on this issue by Polish historian Ewa Kurek in her book Polish-Jewish Relations 1939-1945. [1]

Drawing on predominantly Jewish sources, her research and analysis completely demolish conventional certainties about how guilt for the mass Jewish deaths can be apportioned.

Despite the dates cited in her title, she in fact goes right back into history to provide the context for the situation during the Second World War.

Jews had been living in Poland for about a thousand years, she explains, with their status initially solidified by King Casimir the Great (1333-1370), who passed legal decrees “which pertained to privileges granted to Jews enabling them to establish Jewish settlements on land belonging to Poland”. [2]

Rumours apparently abounded that the Jews gained the favour of the king (pictured) “thanks to the royal banker, Jew Lewko”. [3]

The most important feature of the picture Kurek paints is how separate the Jewish population always remained from the Christian Poles – only a small proportion were assimilated into society in the way we have seen in Western Europe, the USA, Australia and so on.

The Jewish and Polish worlds “existed alongside each other but never actually came into contact with one another. Each one revolved around its own self-sustaining life, barely even catching a glimpse of or tolerating the other, or even feeling any particular need to unite”. [4]

Describing the period between 1580 and 1764, she says: “It is clear that Jews fulfilled a specific role within the economic structures of the civil state.

“They resided in Polish cities, towns and villages, but in Poland they had their own Jewish Parliament, Jewish court system, Jewish religion, and their rhythm of life was dictated by their religion”. [5]

“It must be admitted that this notion of ‘being left to one’s own devices’ was very appealing to Jews, if for no reason other than it did create a sort of ersatz little Jewish state they could call their own”. [6]

Kurek explains that the stable existence on Polish soil of the kahal, the Jewish community, began to break down in the second half of the 18th century.

The abolition of higher structures of Jewish self-government was provoked by “the economic claims of the aristocracy (collecting debts ‘from the synagogues’) on the one hand, and on the other an attempt to curtail the kahal’s ‘plutocratic extortion tactics being imposed on the plebs'”. [7]

While claims of anti-semitism among Poles are often heard, Kurek makes it clear that a certain distrust and even hostility existed on both sides.

She quotes Wladyslaw Bartoszewksi’s account of life in a Jewish community, or ghetto.

“Inside this neighborhood, there was not a single Jew, a homeowner, who would have even considered renting an apartment to a Christian, be that a Pole, a German or a Czech.

“This was an impossibility for a very basic reason: it was a sin for a devout Jew to have an outsider living amongst their own, within their community”. [8]

In his account of the ghetto, Krzysztof Burnetko writes: “Regarding themselves as monotheists, the Jews reckoned that they should not come into contact with any other religion, and particularly with its sacrum.

“For example, in the XIII century orthodox Jews suggested that when Christians walked the streets during the Corpus Christi procession, a religious Jew could not leave his house.

“A similarly motivated advice said that pious Jews should not live in a house whose windows overlooked a church”. [9]

Most Jews in Poland did not even speak Polish, just the Yiddish of their own tightly-knit communities. [10]

Remarks Kurek: “Marian Milsztajn, who was born in 1919 in Lublin, captured the character of the linguistic relations which prevailed in Jewish neighborhoods in Polish cities in the twenty-year period between the wars: ‘The place where we lived… I never heard a single word uttered in Polish.

“‘I didn’t know that such a language existed. As for its existence, I knew that it was the language of the goys. Poland? No idea. I first encountered the Polish language when I was seven years old'”. [11]

Jewish historian Professor Chone Shmeruk explains that Jews often had a strong prejudice against the Latin alphabet in which our European languages are written.

“Regardless of the language in which it was used, this alphabet was associated with Christianity, as is clear from the term ‘galkhes’ (from galekh, Christian priest), the Ashkenazi designation for the Latin alphabet”. [12]

Kurek adds that our alphabet “similarly to other matters associated with Christianity, carried with it the stigma of something contaminated and unclean in its form, and therefore not worthy of the attention of a devout Jew”. [13]

She takes a close look at the origins of a Christian Polish parade featuring Judas as a stereotypical Jewish figure.

And she suggests that it may have emerged as a Polish response to the Jewish celebration of Purim, which marks the news that, in the words of Jewish writer Hilary Nussbaum, “the king has allowed the Jews to assemble and defend themselves against murder or destroy any army of any people which represents a threat against them, not sparing children or women, and to then plunder their booty”. [14]

In this religious story, the arch-enemy of the Jews is Haman. Kurek relates: “In Jewish communities throughout Europe, a custom that had been passed down from Babylonian Jews was that of hanging and burning Haman in effigy…

“Polish Jews dressed the Purim Haman in a cassock. By doing so, the biblical villain and enemy of the Jews came to resemble a Catholic priest in Poland”. [15]

As Rabbi Meir Yaakov Soloveichik has pointed out, hatred is an acceptable part of Jewish religion [16] and Haman represented the evil non-Jewish “Amalek” which had to be destroyed.

In Poland, Jews would even pay some local Christian to play the role of Haman at Purim: “They paraded and pushed him around while beating him with reeds – just like (they did) Jesus”. [17]

This anti-Polish, anti-Christian, anti-gentile prejudice among Jews is every bit as toxic as actual (rather than invented and instrumentalised) anti-semitism – especially today when that particular people has gained so much power in the world.

But the root of the problems between Jews and the local population in Poland seems to have resided mainly in the separation, both physical and psychological, of the two communities.

They simply did not view reality from the same perspective.

Kurek explains, for example, that when Poland lost its statehood at the end of the 18th century, “Polish Jews imagined that the partitions of Poland had very little bearing on the seemingly smooth flow of Jewish life that had gone on for centuries.

“For how could the fact that, as of tomorrow, the Jewish Speaker representing Jewish interests, instead of residing at the Polish royal court, shall reside at the Russian Tsar’s or the Austrian Emperor’s court have any impact on anything?” [18]

This outlook meant that very few Jews, with some honourable exceptions, took part in the long series of battles for Polish independence from foreign control [19] and Polish attitudes towards their Jewish population were inevitably adversely affected by this.

Kurek writes: “During the time of the partitions, Poles needed human solidarity in a way that they had never needed it before, or since.

“They went in search of it to all corners of the world. Above all, they had counted on the solidarity of their fellow-inhabitants, the Polish Jews.

“Berek Joselewicz (pictured), and a handful of likeminded Jews, ignited a hope that other Jews would follow in their footsteps, for they had all grown up on the same land, and therefore must share the same feelings and thoughts”. [20]

That hope of Jewish solidarity with the Polish nation was dashed and the situation became worse in 1812.

Poles had been counting on Napoleon liberating them through his invasion of Russia, but Jews in the country again saw things differently and openly celebrated Napoleon’s eventual defeat.

Jewish legend has it that the famous sage Kozienice Maggid “despised Napoleon with every fiber of his being” because he saw him as an enemy of his religion.

He is said to have declared: “He, Napoleon, drafted Jews into the army and forced them to mutilate their Saturdays and blight other sacred commandments! Let all those who trespass into temptation and sin perish!”. [21]

All of this contributed to a “rapidly expanding and ever deepening chasm between the Poles and Jews”, [22] notes Kurek.

A special Committee to the Matters of the Peasantry and Jews was called and the presiding head arbiter Prince Adam Czartoryski wrote in 1816: “Jews are not indigenous inhabitants of our land. They are nonresidents, foreigners, outsiders”. [23]

A century later the lack of Jewish enthusiasm for Poland was again a bone of contention.

Jewish historian Meir Balaban said of the Polish Jews of Poznan in 1912: “They go around clearly declaring themselves as Germans and they openly express their German patriotism… spin their declaration of love for the Germans”. [24]

Kurek writes: “A mere fragmentary glance at Jewish traditions and religion will suffice in stating that Polish Jews, although they had resided on Polish lands for nearly one thousand years, never identified with Poland as a homeland in the contemporary meaning of the word, that is with the country for whose freedom one sacrifices one’s life…

“First of all, they had a very keen awareness of being members of a nation that had been chosen by God. Secondly, they possessed their own history, and Israel never ceased to be their true sole homeland, for a return to which they prayed at least once a year”. [25]

The Polish reaction to this was to regard Jews in general as having failed the citizenship test and they were not held in high esteem by the newly re-formed Polish state after WWI.

“In characterizing the fight for regaining freedom of their once mutual state as not being a Jewish matter, Polish Jews behaved not like citizens of the Polish State, but rather like foreigners”. [26]

This break-down in trust did not prevent some Jews from seeking a special status in the new Poland.

Kurek writes: “The Zionist Conference that had been in session in Warsaw on October 21 and 22 in 1918, in its resolution pertaining to ‘The matters of politics of the country’ came forth with the demand for granting Jews a constitutional guarantee of a national autonomy within the reconstructed Polish State”. [27]

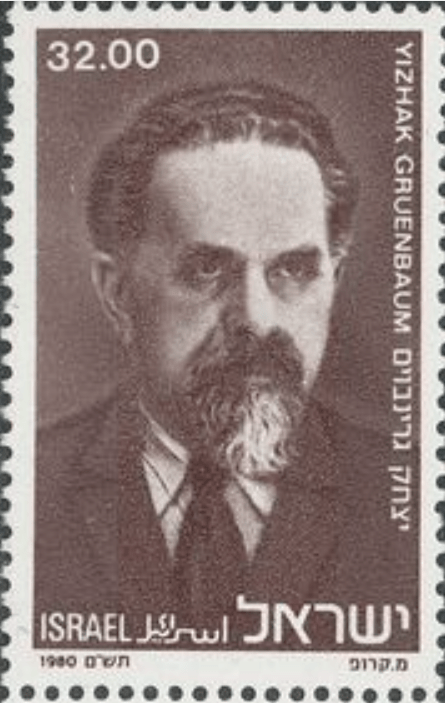

The following year, when the Polish Parliamentary forum was discussing the future Polish constitution for the very first time, Izaak Grünbaum (pictured), who was to become the first Minister of the Interior of Israel, insisted: “We are demanding one thing, that Polish Jewry be granted the ability to organize itself for the sake of meeting our own specific needs that no one else could possibly meet.

“We are not saying that no one else would want to meet these needs, only that no one other than Jews are capable of achieving this…

“We are demanding that we be able to create an organization, based on constitutional principles, that would be obligated to meet the specified needs of Polish Jewry”. [28]

Samuel Hirszhorn said Jews should have their “own self-government to oversee the areas of culture, schooling in one’s native tongue, social services and charity, in other words a national-cultural autonomy”. [29]

It was thus not just a question of asking for equal rights as human beings, which they received, but also for a privileged status as Jews.

Polish opinions of Jews were not improved by the stance of that portion of the Jewish community who supported communism.

These individuals favoured the overthrowal of the “bourgeois” new Polish state, the dismantling of parliament and the “dictatorship of the Proletariat” under close alliance with Soviet Russia.

The Jewish Communist leader Maksymilian Horwitz-Walecki (pictured) condemned former socialist colleagues who took part in the independent Polish state as “clowns, servants, imposters, sell-outs, parasites, kowtowing to festering and hideous bourgeois politics”.

He called for the reconstructed Polish state to be “Destroyed! Defied! Ruined! Overthrown! Annihilated! Reduced to ash! Blown up!”. [30]

Kurek explains that the vast majority of Jews in Poland were not communists, but the stereotype of the “Jew-Communist” stuck in Polish minds as part of a generally unfavourable image.

“The idea that was gaining popularity among Poles was that of designating Jews as burdensome tenants, foreigners in the Polish State who, through emigration to Palestine, for instance, must be (…) removed from public life and deprived of their strong economic standing”. [31]

She says this attitude “had always been perceived by Polish Jews to be anti-Semitism, which we, apparently, suckle with our mother’s milk.

“Perhaps Polish Jews were right. There is no point in trying to conceal the fact that Poles living between the years of 1918 and 1939 had enough with the burdensome Jewish tenants.

“Their desire was that Jews leave Poland alone, and find some other Polin [resting place] in which to lead their lives in prosperity and success. In that sense, they certainly were anti-Semites”. [32]

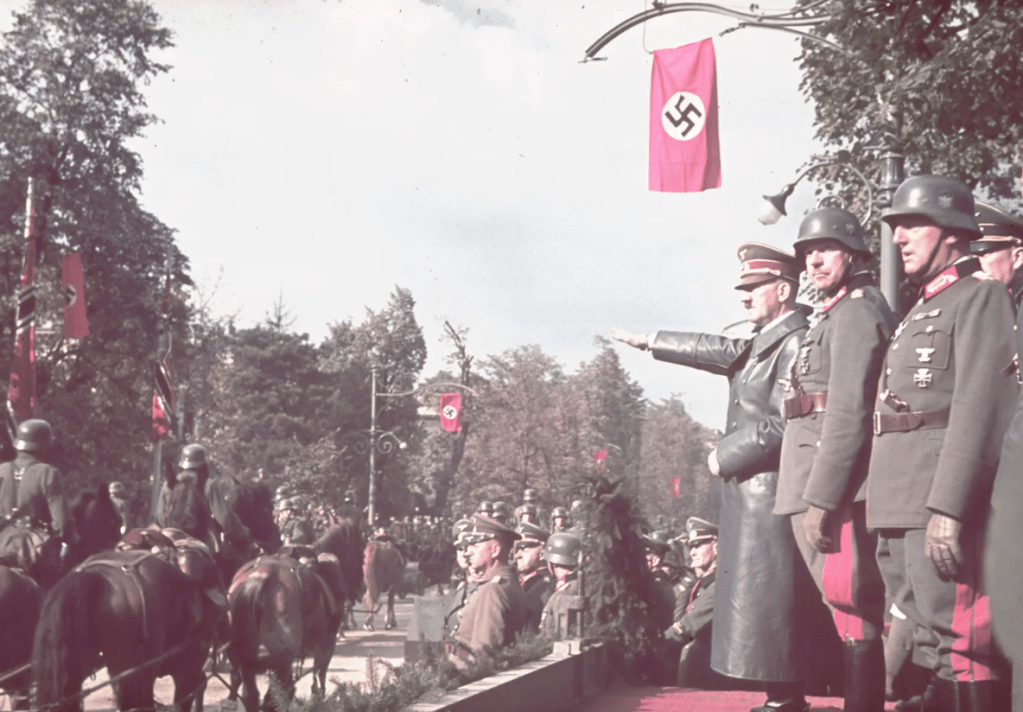

The start of the Second World War in 1939, which saw Poland occupied by the armies of Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s USSR, opened up old wounds in this “multi-national” country.

Ukrainians and Bielorusssians in Poland saw a chance to obtain their own independence and did not join Poles in building their “Underground State” to resist occupation – indeed many collaborated with the Nazis.

And most of the 3.5 million Jews (around 10% of the population) remained focused on “Jewish matters” rather than “Polish matters” of national independence.

Kurek writes: “Communicating using one language, practicing one religion, and being shaped by one culture, the Jewish nation, of which the Polish Jews constituted a significant portion, stretched from Vladivostok to Paris, according to some; according to others, from Odessa to Warsaw. Its specificity was characterized by a lack of allegiance to any specific land or statehood”. [33]

While a small group of Jews formed the Swit (‘Dawn’) resistance movement that later fought in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in 1943, the majority took no such stance.

Conflicts between different non-Jewish states were not something they felt the need to get involved with.

Indeed, it was the Christian Poles who were the initial targets of the Nazi occupiers. Kurek writes: “Today, very few Jewish historians of WWII are willing to remember that the ones who were first in line to bear the brunt of German repression were not Jews, but Poles”. [34]

In his wartime diaries, Jewish historian Emanuel Ringelblum describes reports that some Christians started wearing Jewish armbands so as not be arrested by the German occupiers. [35]

He adds that when the Nazis were rounding up Poles in 1940 “they were checking the identification documents of Jews to make sure they weren’t Christians”. [36] The first prisoners at Auschwitz were in fact Poles, rather than Jews, stresses Kurek. [37]

This was all unfolding in an atmosphere of mutual suspicion between Poles and Jews. Ringelblum writes (March 1940): “One of the saddest symptoms is the ever-increasing hatred towards Christians. It is believed that they are the ones to blame for all the economic restrictions…

“Today I heard that, within Polish intelligentsia circles, there is the belief that Jews have reached an agreement with the other ones [the Nazis] and that that is the reason why all the mass arrests of Christians are taking place”. [38]

The truth is that Polish Jews did cooperate with the Nazi administration – in the same way as Zionist groups did in Germany itself. [39]

Kurek states: “I know of no city or town in Poland occupied by Hitler in which, in 1939, the Jewish community refused to cooperate with the Germans in the broadest sense, and at the same time failed to recognize them as the new governing power”. [40]

Historian Lucjan Dobroszycki describes the case of Chaim Rumkowski (pictured), who became known as “King Chaim” after the Nazis entrusted him with governing the Jewish population of Lodz on their behalf.

“The system of ruling over the Lodz Ghetto was shaped based on imitating Hitler’s Germany”. [41]

“Rumkowski, along with his nomination to the position of Head of Jewish Elders, was also granted a wide range of authorizations within the internal administration of the municipality.

“All of its agendas were subordinated to him. Every Jew was obliged to absolute obedience with regard to the leader.

“It was also simultaneously proclaimed that any opposition against or insubordination to him will be punished by the German authorities.

“The German authorities also gave Rumkowski permission to move about the city at any and all times, and granted him authorized access to German institutions”. [42]

And Ringelblum notes in his diary with regard to Rumkowski’s (pictured on right) own account of his Lodz fiefdom: “There is a Jewish State over there with 400 policemen and 3 prisons. He has a ministry of foreign affairs and all the other ministries as well”. [43]

Adam Czerniakow, mayor of the Warsaw Ghetto, kept a diary in which he recorded the day-to-day co-operation which he eventually regretted and on account of which he apparently committed suicide.

He created, and became president of, a 24-member Judenrat, Jewish Commune.

Explains Kurek: “The Judenrats were instituted by the German occupiers from among individuals displaying a willingness to engage in a multi-faceted cooperation with them, and the scope of their authority, as granted by the Germans, digressed substantially from the traditional capacity of Jewish municipalities”. [44]

Their role included “employing and directing Jews to forced labor for the benefit of the Germans”, she notes. [45]

“The Warsaw Jewish Autonomy and all other Jewish autonomies in Poland, became part of the composition of the III Reich and the former Senator of the Polish State, Adam Czerniakow, along with other mayors of Jewish autonomies, became the state officials representing the German authorities”. [46]

“At the end of 1941, the authorities of the Autonomy of Warsaw Jews were an enormous bureaucratic apparatus, which consisted of more than two thousand employees, which included subordinate institutions. The situation was similar in Lodz, Krakow, in Silesia and other centers of Jewish life”. [47]

In his diary, Czerniakow (pictured) reveals that his very close collaboration with the Nazis included discussing with them what exact wording should feature on his official letterhead! [48]

More significantly, he also records in December 1939 that his authority provided Hitler’s forces “with the addresses of wealthy Jews with the goal of requisitioning furniture, lamps, bedding, etc”. [49]

Jewish authorities even identified for the Germans those Jews who had left the fold and converted to Christianity – from a racially-based Nazi perspective they remained Jews and had to be moved to the ghetto. [50]

Kurek explains that there has been some misunderstanding about the Warsaw Ghetto. It already existed before the German occupation, the only change being that assimilated Polish Jews were forced to go and live there.

And the notorious walling-in of the ghetto in 1940 was ordered by the Nazis but carried out and paid for by the Jewish community.

It was seen by them as a defence against a hostile Polish world, with Czerniakow describing it as “the fortification of the Ghetto area”. [51]

Kurek observes: “In virtually every Jewish source we are able to find praise for being isolated from the Christians, i.e. the Poles”. [52]

Ringelblum records a festive atmosphere in the Nazi-approved walled-off Jewish enclave as late as 1941: “The Ghetto is dancing. The number of nightclubs is multiplying endlessly…

“Jewish policemen fill the most elegant clubs [in the company of] beautiful women. They dictate the tone of all the parties. Women are impressed by their elegant, shimmering, tall officer’s boots”. [53]

He provides this insight into the collaborators: “As it turns out, based on the information from the provinces, in every city there are those Jews who supply the German authorities with everything they need.

“Some provide foodstuffs, others provide clothing… Recently, an interesting type of people has surfaced. Young Jewish activists under thirty, thirty-five, completely unknown before the war…

“They are capable of establishing a relationship with them [the Germans]. They do make a pretty penny doing this”. [54]

We are moving here into the most controversial part of the account given by Kurek (pictured). Her history is revisionist not in that it denies that a mass extermination of Jews took place, but in that it shows that Jews were deeply complicit in this vile crime.

She remarks: “In documentation relating to the Holocaust, the matter of collaboration between Polish Jews and the Germans is rarely touched upon…

“Meanwhile, everything points to the fact that this very issue holds the key to understanding the Holocaust in general, and in turn to understanding the extermination of Polish Jews specifically.

“In other words, one must try to answer the question of whether the Germans would have managed to murder so many millions of Jews had it not been for the fact that, from amongst the Jews themselves, they found eager collaborators and perpetrators of criminal acts”. [55]

“What is revealed ever more definitively is the role of Jews not only as victims, but also as executioners of their own people”. [56]

There was Jewish involvement in nearly every step in the extermination process, from gathering all Jews into the ghettos, and later rounding them up for the Nazis, to fooling them into thinking they were merely being taken to work in the East of Poland. [56]

Kurek concludes that the Germans, fighting a war on two fronts, could not have spared the manpower to themselves do the work carried out by the Jewish authorities and that it was therefore Jewish collaboration which allowed the mass murdering to take place.

“Without the help of Polish Jews, it would have been extremely difficult for the Germans to realise their plan of annihilating Polish Jews”. [57]

Ringelblum describes the indignation expressed by Szachno Efroim Sagan at the way the Nazi-approved Jewish police (pictured) in Warsaw directed the programme of “deportation” – to the concentration camps – in 1942.

“He felt that the Jewish community, despite German threats, should have refused to participate in the campaign. It would have been better if the Germans did it themselves.

“Sagan went to the Judenrat to file his complaint against the disgraceful manner in which they were behaving in taking on the role of executioner and assistants to the murderous SS”. [58]

“He couldn’t stand by and watch as the Jewish Ordnungsmänner [police] captured Jewish children and shoved them into the back of the trucks bound for Umschlagplatz.

“He couldn’t bear the sight of women being dragged by their hair by their Jewish captors from the Ordnungsdienst“. [59]

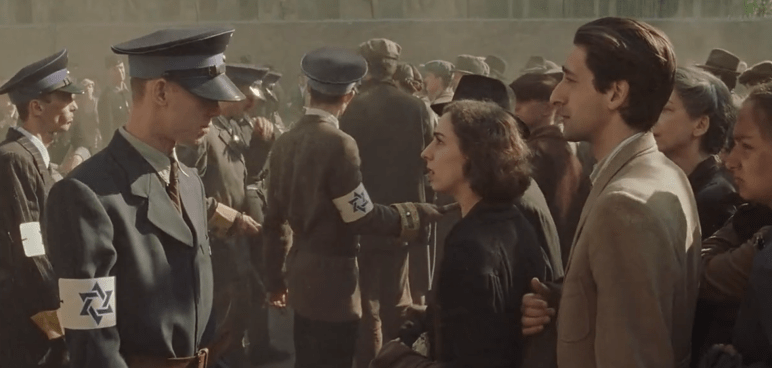

Wladyslaw Szpilman (pictured), whose autobiographical book The Pianist was later turned into a film by Roman Polanski, paints a vivid picture of the Jewish police in Warsaw.

He writes: “They have been infected with the winds of the Gestapo. It seems the only way to describe it. The moment they donned their uniforms and took the clubs in their hands, they turned into animals…

“When it came time to execute the round-up in May, they surrounded the street with the sharp precision of seasoned, pure-SS men.

“They were running around in their stylish little uniforms, barking loudly and fiercely as expertly as the Germans, and they beat people with their rubber clubs”. [60]

“They were no less dangerous or merciless than the Germans, perhaps even meaner and more base than them.

“When they found people who had hid rather than come down to the courtyard, they were easily bribed.

“But they accepted only money. Neither tears, nor begging, nor the heartbreaking screams of children were enough to move them”. [61]

A re-enactment of shocking scenes of Jews being rounded up by the Nazi-serving Jewish police can be viewed in Polanski’s 2002 film, [62] as you can see from the screenshots below, plus that at the top of the article.

The poet Icchak Kacenelson, who died at Auschwitz, expressed it thus:

“Traitors who ran up the empty streets in their shiny shoes.

“As though with the Swastika emblazoned on their hats – they charged angrily wearing the Star of David”. [63]

Ringelblum describes the Jewish police at Umschlagplatz under the command of the Jewish officer Mieczyslaw Szmerling (pictured below, front left).

“The criminal giant Szmerling, with a horsewhip in his hand. He has entered into the good graces of the Germans. The loyal executor of their commands.

“The Jewish police had a bad reputation even before the deportations began. Unlike the Polish police which did not participate in the work camp round-ups, the Jewish police engaged in this repugnant act.

“They were the epitome of corruption and demoralization… Not one word of protest was uttered against their despicable function which entailed leading their own brothers to slaughter.

“The police were spiritually dedicated to this filthy job and, therefore, performed it willingly and eagerly”. [64]

He adds that the police were not the only Jewish collaborators involved in the “deportation” to the camps.

“There were groups and organizations outside the police which voluntarily showed their support for and participated in the deportation campaign.

“At the top of this list was the Gancwajch Ambulance Service, a faux institution in amaranth hat, which not once, not ever, provided any medical attention to a single Jew…

“This criminal gang of troublemakers volunteered to do the ungodly job of sending Jews to the other world.

“It was this gang that was the epitome of brutality and inhumane acts. Their red hats became covered with the blood splatter of the unfortunate Jewish masses.

“Aside from the Gancwajch Ambulance Service, the deportation campaign was helped along by Jewish Community office/administrative assistants/clerks, as well as by the KOS Ambulance Service”. [65]

A quick glance at Wikipedia reveals that the Gancwajch Ambulance Service was set up by Abraham Gancwajch (pictured), described as “a Jewish kingpin of the ghetto underworld” – a gangster/racketeer and also a Zionist. [66]

The entry notes that Czerniaków mentions Gancwajch in his diary as “a despicable, ugly creature” and that Gancwajch “is also known to have tried to sabotage attempts at the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising”.

In stark contrast to these vile Jewish collaborators, the Polish Underground State punished Poles who worked with the Germans and also set out to inform the world of what was happening to the Jews.

To this latter end, a special courier of the Polish Government in Exile, Jan Kozielewski (aka Jan Karski), was sent to the UK and the USA to sound the alarm and seek help in preventing the extermination.

He recalls his exhaustive visit to the USA, in which he even met President Franklin Roosevelt: “I also met with Supreme Court Judge Felix Frankfurter (pictured), who after listening to me said, ‘Do you know that I am a Jew?’. I nodded. Frankfurter continued ‘I am unable to believe you’.

“In Great Britain and the United States, I informed the top people of these world powers of what I had seen.

“I had spoken with Jewish leaders on both continents. I talked about what I had seen with renowned authors: Herbert G. Wells and Arthur Koestler, as well as with members of the PEN Club in England and in America.

“They possessed talent and renown. They possessed the ability to describe this better than I ever did. Did they do this?”. [67]

The reason for the inaction is obvious once one knows, as my regular readers do, that the Nazi regime was nothing but a Zionist golem.

The mass extermination of Jews had to go ahead, because it was all part of the Big Plan.

This presumably also explains the active and eager involvement of Zionist organised crime in rounding up Jews in Poland.

But the question still remains as to how, on a human level, it was possible for Jews in Poland to participate in the slaughter of their co-religionists.

There was certainly a class element involved. Kurek says that, according to Ringelblum, the majority of the Jewish police were from the intelligentsia and were lawyers before the war. [68] Szpilman also remarks that the Jewish police force “was composed mostly of well-to-do young people”. [69]

The victims, on the other hand, were considered by wealthy Jews to be “the lowlifes” – as Ringelblum tells us. [70] They were seen as less useful and productive members of what Kurek terms “a caste society from the dawn of history”. [71]

She also refers to the traditional Jewish outlook that presents “the option of sacrificing the lives of a few Jews with the purpose of saving the lives of the remaining Jewish community”. [72]

Or, perhaps, with the purpose of enabling the creation of the state of Israel and the ensuing glorious victory of the Jewish nation over all its many enemies?

She writes: “It was necessary to sacrifice the lives of those less productive and save the working part of the people.

“The decision about who was supposed to play the role of the condemned and who the role of the survivors in this horrible theatre of Jewish sacrifice and survival was made, in accordance with Jewish tradition, by the elite – the clerks within the Jewish community”. [73]

I am reminded of the remarks by Professor Yakov Rabkin (pictured) about the way in which some Jews, particularly from Eastern Europe, consider that their own people can justifiably be allowed to die in the name of the greater Cause. [74]

He refers to the 1938 statement by David Ben-Gurion (1886-1973), the future founder of the state of Israel, that: “If I knew that all Jewish children could be saved by having them relocated to England, but only half by transferring them to Palestine, I would choose the second option, because what is at stake would not only have been the fate of those children but also the historical destiny of the Jewish people”. [75]

A similar position was taken by the aforementioned Grünbaum during a 1943 discussion about the suggested allocation of some “Zionist money” for rescuing Jews from extermination.

He insisted: “I think it is necessary to state here – Zionism is above everything… I will not demand that the Jewish Agency allocate a sum of 300,000 or 100,000 pounds sterling to help European Jewry. And I think that whoever demands such things is performing an anti-Zionist act”. [76]

I would say that this statement, whose meaning is all too clear, completely flips the moral lesson we are supposed to have learned from the Holocaust – particularly when combined with all that we know about the real origins of the Nazi regime and the Jewish networks which collaborated with it.

Instead of boosting Zionism and providing it with unique historic opportunity to assert its power, the mass murder of Jews 80 years ago, when properly understood, should sound the death knell for Zionism.

We see exposed not just the loathsome hypocrisy of Zionists in using the Holocaust, which they enabled, as the moral high ground from which they like to look down on the rest of us, but also the near-unbelievable inhumanity that always seems to characterise the actions of ZIM, the zio-satanic imperialist mafia.

Rabkin remarks of that chillingly callous attitude: “This prioritization of the collective Cause versus individual lives likens Zionism to a modern-day Moloch, seemingly insatiable and demanding more and more human sacrifices to this day”. [77]

This very dark area of Jewish tradition is also raised by Tomasz Tulejski and Arnold Zawadski, two Polish academics whose work I explored in an essay on Thomas Hobbes and Leviathan’s Law. [78]

What I did not include in that piece is this rather disturbing analysis: “Although the idea of Yahweh’s kingship over Israel (Ps 114:2) and the entire universe (Ps 47:9; 97:1; 99:1; 103:19; 146:10) is very present in the Hebrew Bible, already in very old texts, the title ‘king’ to describe God Yahweh appears extremely rarely, and the first to dare use it so directly was Isaiah (Is 6:5).

“Such a sparing use of the term ‘king’ (ְmelek) to describe Yahweh by biblical authors of the monarchical period was probably caused by anti-Canaanite polemics, which did not allow for the possibility of Yahweh being similar to El, the highest god of the Canaanite pantheon, called malku – ‘king’.

“It is also possible that the sound of the Hebrew word melek itself was associated with Moloch, the Phoenician deity to whom children were sacrificed – a custom practiced by the Israelites during the Israelite monarchy (2 King 23:10; cf. also 2 Kings 16:3)”. [79]

[1] Ewa Kurek, Polish-Jewish Relations 1939-1945: Beyond the Limits of Solidarity (Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse, 2012). All subsequent page references are to that work, unless otherwise indicated.

[2] p. 16.

[3] p. 162.

[4] p. 41.

[5] p. 62.

[6] p. 63.

[7] p. 64.

[8] W Bartoszewski, Warto byc przyzwoitym (‘It is worthwhile being decent’), (Paris: Editions Spotkania, 1986), p. 25, cit. p. 43.

[9] K. Burnetko, ‘Getto: od azylu do Zaglady’ (‘The Ghetto: from asylum to Extermination’), in Polityka No 1/2008, s. 47, cit. pp. 44-46.

[10] p. 42.

[11] Sciezki pamieci (‘The path of recollecion’), ed. by Jerzy Bojarski, Lublin, 2002, pp. 69-70, cit. p. 142.

[12] Ch. Schmeruk, The Esterke Story in Yiddish and Polish Literature, Jerusalem, 1985, p. 48, cit. p. 149.

[13] p. 150.

[14] H. Nussbaum, Przewodnik Judaistyczny obejmujacy kurs literatury i religii (‘A Judaic guide including the course of literature and religion’), Warsaw, 1893, pp. 124-130, cit. p. 134.

[15] p. 137.

[16] https://winteroak.org.uk/2026/01/05/hate-supremacism-and-the-satanic-world-order/

[17] A Cala, Wizerunek Zyda w polskiej kulturze ludowej (‘The image of a Jew in Polish popular history’), Warsaw, 1992, pp. 85-89, cit. p. 153.

[18] pp. 66-67.

[19] p. 70.

[20] p. 72.

[21] Meir Balaban, Dzieje Zydow w Galicyi (‘A History of the Jews of Galicia’), Krakow, 1914, pp. 86-88, cit. p. 78.

[22] p. 76.

[23] A. Eisenbach, Emancypacja zydowska na ziemiach polskich 1785-1870 (‘Emancipation of Jews on Polish Lands 1785-1870’), Warsaw, 1988, p. 176, cit. p. 76.

[24] M. Balaban, Dzieje Zydow w Krakowie I na Kazimierzu 1304-1868 (‘A History of the Jews in Krakow and in the Kazimierz District 1304-1868’), Krakow, 1912, pp. 162-63, cit. pp. 83.

[25] p. 87.

[26] p. 93.

[27] p. 94. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yitzhak_Gruenbaum

[28] Stenographic reports from the Legislative Polish Parliament, pos 37, May 13, 1919, I 5-6, cit. p. 95.

[29] Stenographic reports as above, I 66, cit. p. 95.

[30] J. Olczak-Ronikier, Wogrodzie pamieci (‘In the garden of memory’), Krakow, 2002, p. 156, cit. p. 102.

[31] p. 108.

[32] Ibid.

[33] p. 184.

[34] p. 298.

[35] E. Ringelblum, Kronika getta warszawskiego wrzesien 1939 – styczen 1943 (‘Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto September 1939 – January 1943’), Warsaw, 1983, p. 98, cit. p. 298.

[36] Ringelblum, p. 98, cit. p. 299.

[37] p. 299.

[38] Ringelblum, pp. 118-19, cit. p. 301.

[39] Paul Cudenec, ‘The Nazi regime was a Zionist golem’, https://winteroak.org.uk/2026/01/08/the-acorn-108/#2

[40] p. 196.

[41] L. Dobroszycki, preface to Kronika getta lodzkiego (‘The Lodz Ghetto Diary’), Lodz, 1965, p. xxi, cit. p. 205.

[42] Dobroszycki, p. xviii, cit. p. 199.

[43] Ringelblum, p. 154, cit. p. 201.

[44] p. 199.

[45] Ibid.

[46] p. 202.

[47] p. 203.

[48] A. Czerniakow, Dziennik getta warszawskiego 6.IX.1939 – 23.VII.1942 (‘The Warsaw Ghetto Diary 6/9/1939 – 23/7/1942’), May 31 1941, cit. p. 201.

[49] Czerniakow, December 12, 1939, cit. 219.

[50] p. 352.

[51] Czerniakow, September 30, 1940, cit. p. 208.

[52] p. 215.

[53] Ringelblum, p. 240 & p. 254, cit. pp. 214-15.

[54] Ringelblum, pp. 78-79 & p. 103, cit. p. 220.

[55] p. 227.

[56] p. 228.

[56] pp. 238-39.

[57] p. 262.

[58] Ringelblum, p. 71, cit. pp. 229-230.

[59] Ringelblum, summer of 1942. No page reference provided, cit. p. 230.

[60] W. Szpilman, Pianista (‘The Pianist’), Krakow, 2003, p. 85, cit. p. 235.

[61] Szpilman, p. 86, cit. p. 240.

[62] https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x9lmls2

[63] I. Kacenelson, Piesn o zamordowanym narodzie zydowskim (‘The Song of the Murdered Jewish Nation’), Warsaw, 1982, p. 23, cit. p. 248.

[64] Ringelblum, p. 404 & p. 407, cit. p. 245.

[65] Ringelblum, p. 410, cit. p. 246.

[66] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham_Gancwajch

[67] J. Karski, Tajne panstwo (‘The Underground State’), Warsaw, 1999, pp. 288-290, cit. p. 333.

[68] p. 234.

[69] Szpilman, p. 85, cit. p. 235.

[70] Ringelblum, p. 268, cit. p. 281.

[71] p. 282.

[72] p. 278.

[73] p. 279.

[74] Yakov Rabkin, Israel in Palestine: Jewish Rejection of Zionism (Atlanta: Aspect Editions, 2025). See Paul Cudenec, ‘Zionism, Nazism and Moloch’, https://winteroak.org.uk/2025/12/16/zionism-nazism-and-moloch/

[75] Dina Porat, ‘Une question d’historiographie: L’attitude de Ben-Gurion à l’égard des juifs d’Europe à l’époque du génocide’ in Florence Heymann and Michel Abitbol, eds, L’historiographie israélienne aujourd’hui (Paris: CNRS éditions, 1998), p. 120, cit. Rabkin, p. 89.

[76] https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Yitzchak_Gruenbaum

[77] Rabkin, p. 91.

[78] Paul Cudenec, ‘Leviathan’s Law and the occupation of our lands’, https://winteroak.org.uk/2025/11/04/leviathans-law-and-the-occupation-of-our-lands/

[79] Tomasz Tulejski, Arnold Zawadzki, ‘Golem i Lewiatan. Judaistyczne źródła teologii politycznej Thomasa Hobbesa’, 2019, Politeja, № 2(59), p. 207-232, Ksiegarnia Akademicka Sp. z.o.o., p. 223.

https://journals.akademicka.pl/politeja/article/view/1147/990