A book review by Paul Cudenec, who reads it here

“I regard modern society as shabby, tawdry, and incredibly stupid; destructive and self-destructive beyond belief”. [1]

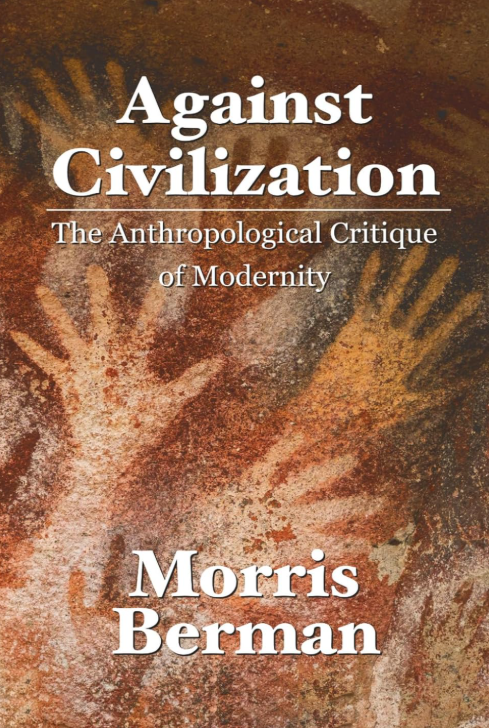

So writes Morris Berman in a new book entitled Against Civilization: The Anthropological Critique of Modernity, which he describes as “the story of ten great thinkers who saw through time”. [2]

A thread running throughout these profiles of anthropologists is the urgent need for a big change in the way we live and think.

The term “change” – along with variants like “social change” and “systemic change” – has been polluted somewhat by its co-option by globalists.

The very name of The Tony Blair Institute For Social Change sends an icy Davos chill down my spine!

And there were moments in this book when I wondered if we were looking at proponents of that unwelcome kind of change that seeks to remodel humanity to suit the exploitative agenda of our overlords.

One of these came when Berman uses the phrases “social change” and “social engineering” [3] to describe the work of Ruth Benedict (1887-1948), pictured.

A further alarm bell sounded in my head when I learned that, during the Second World War, the American government “commissioned her to investigate the national character of the Japanese, so that the US could better prosecute the War and the subsequent Occupation”. [4]

But, funnily enough, the book that came out of that research (The Chrysanthemum and the Sword) proved very popular in Japan and ended up, in many people’s eyes, making Japanese culture of the time look superior to the American Way.

Its emphasis was on order and respect for tradition and on the primacy of spirit over matter, with the Japanese seeing the war as a “conflict between their faith in the Japanese spirit vs. the American faith in matériel and technology”. [5]

Remarks Berman with regard to Benedict: “I confess that I am a bit confused about what she ultimately believed in, and I’m not sure if the confusion is within me or within Ruth”. [6]

A similar ambiguity surrounds Margaret Mead (1901-1978), who “had a deep intellectual and romantic relationship with Ruth Benedict”. [7]

While addressing the root causes of war and environmental destruction is entirely laudable, the inclusion of “population control” in her vision of “building a new world”, [8] is a bit of a red flag.

Moreover, Mead (pictured) “received twenty-eight honorary degrees, and collected a large number of awards and appointments, including the presidency of the American Association for the Advancement of Science” and “in 1998, her face appeared on the 32-cent stamp”. [9]

When someone is also a frequent guest on popular TV shows, is acclaimed by Time magazine as “Mother to the World” [10] and her books receive “rave reviews” from “a star-studded cast”, [11] one has to wonder what kind of “change” agenda she was, wittingly or not, serving.

The real change we need is to exit from the corrupt system that only dishes out such acclaim to individuals who bolster, or at the very least pose no threat to, its domination.

In an age of desecration and destruction, those of us who would prefer cohesion and continuity – and who might thus in other circumstances be regarded as socially conservative – find ourselves radical opponents of a system that represents all that offends us most.

As Berman remarks of his own country: “One could easily argue that the brutality of contemporary America, and certainly its current administration, has never been uglier, or more intense. America is essentially about predation, exploitation, and unchecked narcissism”. [12]

“And all the while, slaughter and starvation continue in Palestine, while the rest of the world just looks on and does nothing. Add to which the slaughters in Ukraine and elsewhere. Welcome to the modern ‘civilized’ world.

“Who, really, are the savages? Western neoliberals, with their world of war and genocide and hustling and competition and plutocracy and endless desire to show off (and the wokes, with their tiresome virtue-signaling), or the indigenas, with their inherent modesty, and their kinship worldview?” [13]

With any dream of discovering a wholesome non-industrial world usually dismissed as “romantic”, Berman refers approvingly to the sociologist C. Wright Mills’ designation of defence of the contemporary hell as “crackpot realism” – “What Mills was saying is that we’ve got the world upside down; our priorities are completely inverted”. [14]

Berman describes the notion of a “runaway” society as set out by Gregory Bateson (1904-1980) – who, incidentally, was inspired by fellow Englishman William Blake, the organic radical opponent of industrial modernity whose art heads this article. [15]

This runaway society is the opposite of a homeostatic society, which manages to self-correct and maintain itself at an optimal point.

On an individual level, this latter approach would involve, for example, taking a vitamin or mineral supplement at the correct dosage rather than stuffing as much as possible down your throat in the hope that the sheer quantity will make you super-healthy.

Berman says that since the Industrial Revolution our society has been dominated by “the goal of unlimited expansion, maximizing profit in a capitalist society. Here we do say ‘The more the better’. The result? Capitalism has, for a long time now, been in runaway, and it is clearly destroying our lives, our environment, and – itself”. [16]

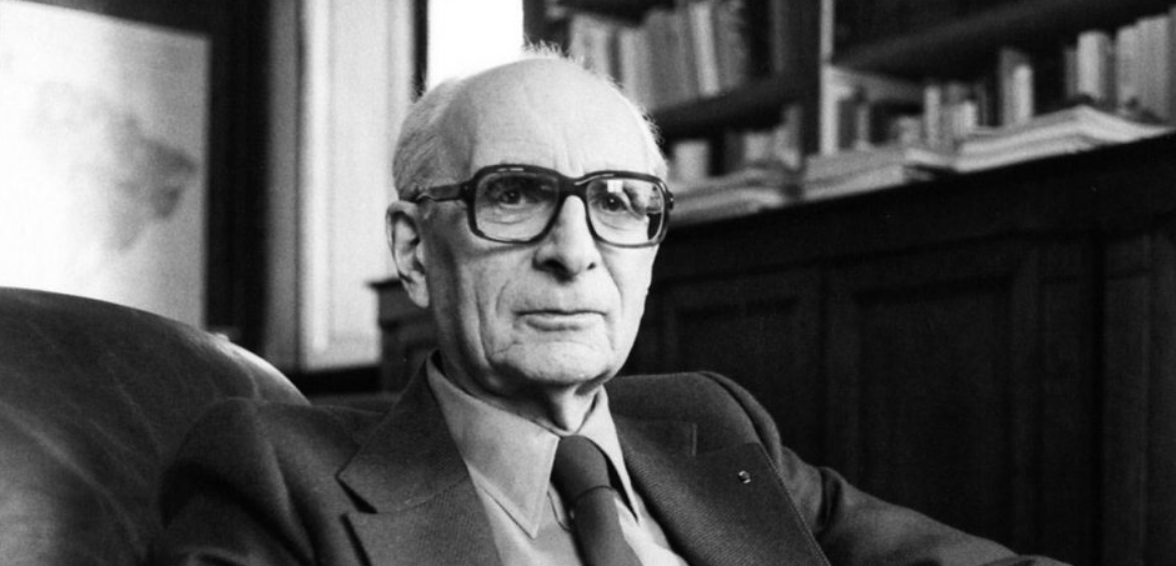

In his profile of Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009), pictured, he explains how the French intellectual denounced “mass civilization” and “monoculture” and expressed disgust with the West and what he called “its own filth, thrown in the face of mankind”. [17]

But the depths to which this modern world has sunk are, of course, not generally considered a suitable topic for the industrial system’s own media or academic mouthpieces.

Writes Berman: “We need to consider the endless propaganda that surrounds us on a daily basis, broadcasting the notion that our lives are so much better than they were in previous times.

“We are literally soaking in this ideology of progress (or more accurately, ‘progress’) which is so pervasive that we don’t realize that it’s an ideology…

“Most of the citizens of modern industrial society experience their lives as oppressive, a rat race, the ‘daily grind’. They live for weekends (TGIF), holidays, retirement, and call this ‘life'”. [18]

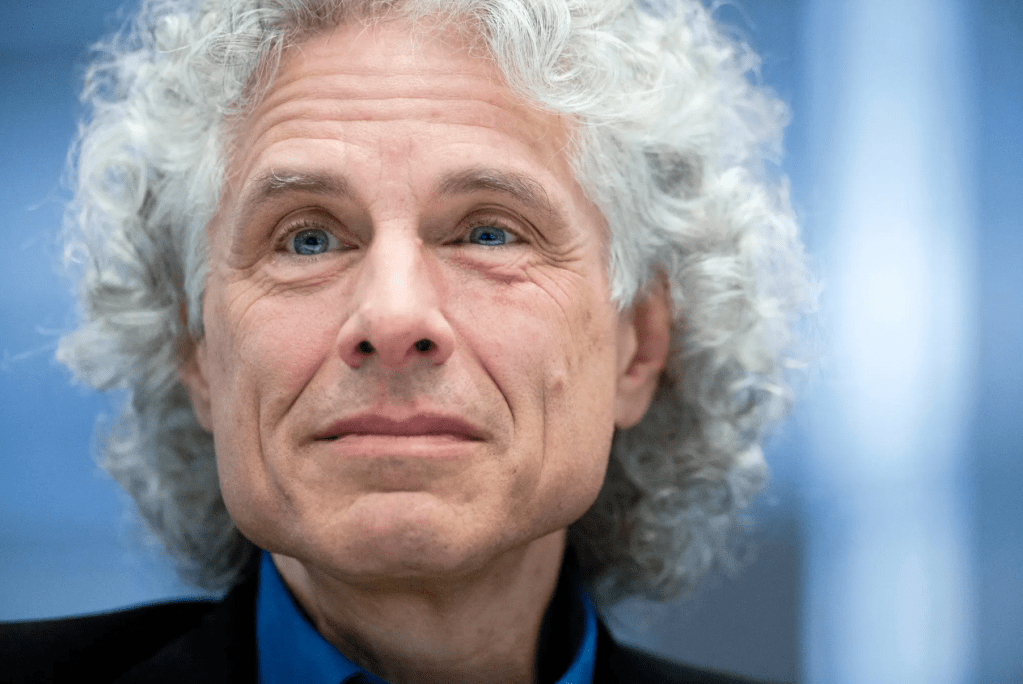

He points to Steven Pinker as one particularly insidious propagandist for the modern ideology, with works such as The Better Angels of Our Nature and Enlightenment Now.

Berman remarks: “The latter book was pretty much reduced to ashes by the British philosopher John Gray, who pointed out that ‘the message of Pinker’s book is that the Enlightenment produced all the progress of the modern era and none of its crimes’. [19]

“Pinker (pictured) comes off as a fool, a high-IQ moron… Not surprisingly, he has a large following, including Bill Gates, another non-historian, who has praised Pinker’s work to the skies”. [20]

Underlying all the propaganda is the assumption that modern industrial society, sometimes called “the West”, is the pinnacle of human achievement, as opposed to those lowly parts of the world that are said to be “underdeveloped”.

Berman refers to Muslim intellectual Shahid Bolsen’s view that this “is a term that the West likes to apply to those countries that lag behind the West in terms of economic and technological expansion and industrial growth, which are seen as the purpose of life.

“But these, Bolsen argues, are not the only possible yardsticks, or criteria, of development. The West, he tells us, is underdeveloped in terms of morality, spirituality, ethics, equality, sustainability, community, and so on. It seems hard to argue with this”. [21]

Large parts of the book are devoted to discussion of what Berman describes as “the concepts of cultural relativism and ‘reverse superiority'”. [22]

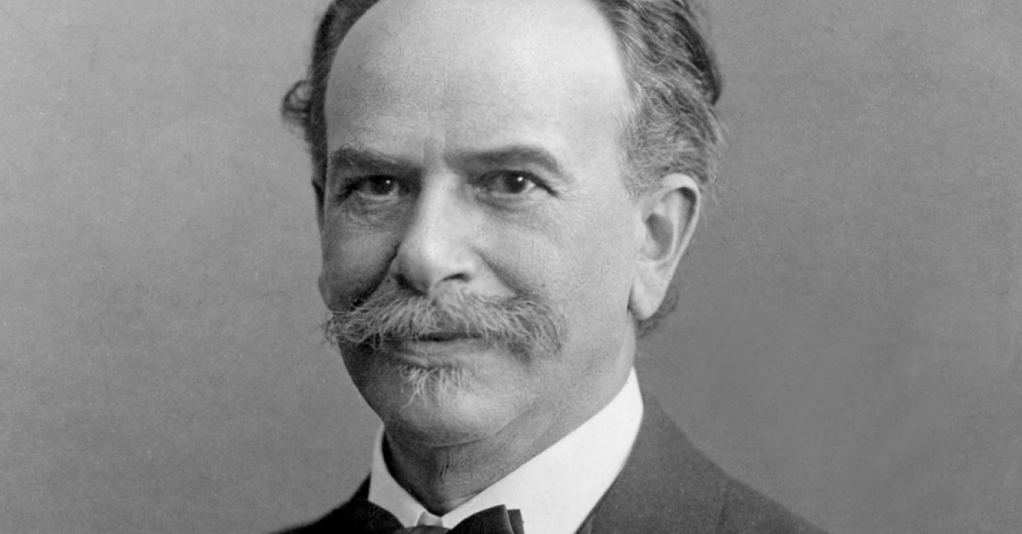

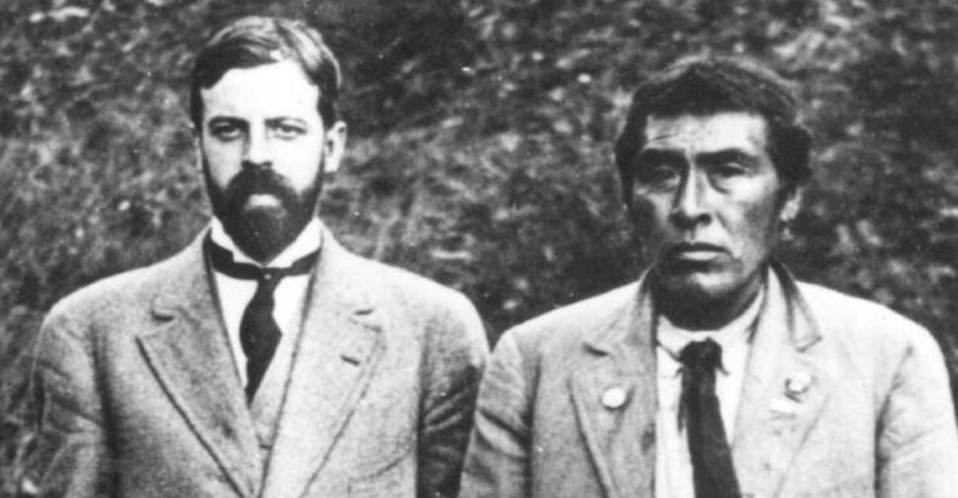

He looks, for instance, at the work of Franz Boas (1858-1942), the “father of American anthropology”. [23]

“All of the world’s peoples, said Boas (pictured), had created unique cultures, ones that were complex and beautiful, hardly stages on the way to becoming ‘civilized’.

“As a result, he concluded, there are no superior cultures… in fact, primitive art and languages were in many cases more complex and sophisticated that their Western counterparts”. [24]

Berman explains that the same position was taken by Lévi-Strauss, who argued “that there was no such thing as a superior society”. [25]

An important book in this respect was Stone Age Economics by Marshall Sahlins (1930-2021), which describes an “original affluent society” of hunter gatherers.

Berman notes that conventional wisdom considers such people to live “pretty desperate lives, constantly scrambling to survive, in what is labeled a ‘subsistence economy'”. [26]

But, he says, this term better describes modern living, desperately working to try to meet manufactured needs – “the life of a hamster on a wheel”. [27]

Sahlins insists that this is not the only possible approach: “There is also a Zen road to affluence [which recognizes that] human material wants are finite and few…

“Adopting the Zen strategy, a people can enjoy an unparalleled material plenty – with a low standard of living”. [28]

“A good case can be made that hunters and gatherers work less than we do; and, rather than a continuous travail, the food quest is intermittent, leisure abundant and there is a greater amount of sleep in the daytime per capita per year than in any other condition of society”. [29]

In addition, as Berman points out, hunter gatherer societies “lasted for millennia”, whereas industrial society seems to be “on its last legs, culturally, economically, politically, and especially, ecologically” after just a few centuries. [30]

Part of the reason for their endurance (actual sustainability!) may well be because of the way they saw off the danger of coercive power.

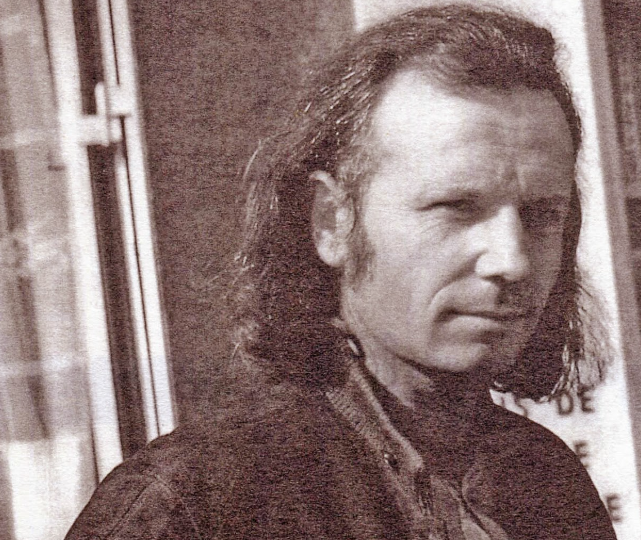

Writing about his studies of Amerindian peoples, Pierre Clastres (1934-1977) writes that it is “as though these societies formed their political sphere in terms of an intuition.

“They had a very early premonition that power’s transcendence conceals a moral risk for the group… Indian societies were able to create a means for neutralizing the virulence of political authority”. [31]

Berman explains that Clastres found, with various tribes, that “there was very little concentration of authority among these peoples. Power was not considered coercive, and the leaders, or chieftains, were in fact powerless.

“They had prestige, to be sure, but the system was monitored (if that’s the right word) so as to prevent the leader from transforming his prestige into coercive power.

“To be specific, these societies possessed cultural mechanisms (also known as levelling mechanisms) designed to prevent the emergence of coercive power figures…

“Clastres (pictured) was very critical of the conventional evolutionary view, which saw the State, or hierarchical societies in general, as being more developed than primitive ones; as being superior, in a word”. [32]

Clastres’ 1974 book Society Against the State obviously presented a significant challenge to the assumptions on which contemporary authority depends and he has frequently been attacked for his views.

Says Berman: “He has been accused of being an anarchist, at least, which may not be entirely off the mark.

“And of course, that might be a good thing. Let’s just state it plainly: Pierre Clastres was not merely a remarkable anthropologist; he is also one of the most courageous people in modern memory”. [33]

Clastres’ story is a tragic one. Augusto Gayubas describes how his “research work was abruptly interrupted in 1977 when a car accident ended his life, but his disruptive thinking and active personality keep him present as a ghost among those who make their best efforts to silence the political consequences of his work”. [34]

One man involved in these efforts to dispatch Clastres down the memory hole was the late American anthropologist Clifford Geertz (pictured).

Berman says he did not do so with argument but with “a dismissive string of sarcasms”. [35] “Clastres frightened Geertz, so in lieu of mounting a serious scholarly critique, he attempted to discredit him, erase him from professional consideration. Happily, he failed”. [36]

The root of the non-modern way of being, and its resistance to coercive power, lies in a sense of what I call withness. [37]

A “primitive” person, says Jean Cazeneuve, “does not see himself as a creature distinct from all beings and things which surround him”.

There is a “kinship of essence between all things, animate or inanimate. The spiritual is not distinct from the material”. [38]

This ancient way of being human calls out to the prisoners of modernity like the view of distant lush green hills through the bars of their cells.

Berman looks at the work of Alfred Kroeber (1876-1960), father of the writer Ursula K. Le Guin (hence the “K”). [39]

He says that he “is essentially known today for one particular thing: his close friendship with, and protection of, the last living member of the Yahi tribe, a man named ‘Ishi’ (which means ‘man’ in the Yana language; no-one ever found out his real name), who was discovered outside Oroville, California, in 1911, and who died of tuberculosis in 1916”. [40]

“As soon as the existence of Ishi (pictured with Kroeber) was made public, Americans went nuts over him. He became a hero to Californians, a man of myth and mystery.

“Photos of him were purchased as treasured mementos. Women sent him food and clothing; people wanted to learn everything about him”. [41]

“What was going on here? What was the psychology of all this, that Ishi could generate such excitement? We can never know for sure, but my own guess is something like this: in Jungian terms, Ishi was a ‘shadow’ figure for civilization. He was everything Americans were not, but perhaps secretly wanted to be”. [42]

“Kroeber said he was the most patient man he ever knew; that he radiated a deep sense of contentment. Very few Americans, or Westerners in general, fit that description: in fact, pretty much the opposite is true”. [43]

Douglas Sackman remarks: “Ishi was and continues to be so fascinating in large part because his story seemed to represent an alternative to the modern world”. [44]

So how might we ever manage to “recapture wholeness from an increasingly fragmented and alienating modernity”, [45] as Richard Lee has put it?

I would say that an essential step is to become deeply aware of our belonging to that wholeness, of our withness, and to allow that to guide our thinking and our actions.

Berman voices some pessimism about the possibility of ever changing human character, and thus society as a whole.

I think that would be valid if the society in which we lived was actually a reflection of general human character.

But, in fact, as I touched upon at the start of this piece, it amounts to a denial of everything that feels good and proper to most of us.

Its mindset is one that has been imposed upon us by overlords who have seized coercive power to exploit and enslave us.

The reality of our nature, denied and hidden from us, would tell us to live quite differently if only we would listen to it, rather than to the relentless propaganda of power.

That is why the American public were so enthralled by Ishi and that is why the work of Clastres and Sahlins has inspired so many.

Because our real nature and needs as human beings are diametrically opposed to the life that we are offered today, we can feel completely out of place, alienated.

This is “the struggle between the individual and their culture, in particular when you don’t fit in, when you recognise that you are an outsider, even a misfit, when you are at odds with your culture’s values”. [46]

Modern society is like a grid which has been placed over humankind with the command that we should stay in our little boxes, just as we were supposed to stand on the social-distancing circles during the Covid scam.

This, they tell us, is how a society can be orderly and structured.

But the truth is that we don’t need their artificial and imposed “order”, because we already have natural order in our hearts, through our withness.

This natural order, the structure underlying everything, is what Gregory Bateson’s father William called “the patterns and recurrence of patterns in animals and plants”. [47]

“We commonly think of animals and plants as matter, but they are really systems, through which matter is continually passing.

“The orderly relations of their parts are as much under geometrical control as the concentric waves spreading from a splash in a pool”. [48]

Son Gregory carried on in the same vein: “I picked up a vague mystical feeling that we must look for the same sort of processes in all fields of natural phenomena – that we might expect to find the same sort of laws at work in the structure of a crystal as in the structure of society, or that the segmentation of an earthworm might really be comparable to the process by which basalt pillars are formed”. [49]

Berman identifies a similar concept in Lévi-Strauss’s structuralism, “a mode of analysis that focuses on the relationships among elements in a conceptual system.

“Structuralism has a Platonic flavour to it, as in the Parable of the Cave in The Republic: it seeks the ‘true reality’, the light behind the shadows, the patterns that underlie the surface appearances”. [50]

It is a holistic approach, shifting emphasis away from single objects or cultural practices “to the study of the relationships among those objects”. [51]

The underlying structure of the living cosmos can manifest in human thoughts in the form of myth, which Lévi-Strauss regarded as operating in people’s minds without their being aware of it. [52]

If we want to reclaim our withness and become again fully operative parts of the organic Whole, we have to cast off the mental chains that are preventing us from doing so.

The psychologist Merlin Donald considered that the human race passed through a Mimetic stage of imitation and representation, such as dance and music, and then a Mythic stage which was all about speech and storytelling.

We are now in the Theoretic stage focused on critical thinking, writing and analysis, although elements of the previous stages are still present. [53]

Explains Berman: “If analytic thinking can do things that the other two modes can’t, he [Donald] says, it is nevertheless the case that these latter modes are ‘extremely subtle and powerful ways of thinking. They cannot be matched by analytic thought for intuitive speech, complexity, and shrewdness'”. [54]

He tells how Lucien Lévy-Bruhl (1857-1939) argued that “human beings have a mystical, creative side that transcends the logic of rational thought”. [55]

Biographer Jean Cazeneuve says that, for Lévy-Bruhl, “mystical thought responds to a need in human nature, for rational knowledge cannot be fully satisfying.

“It separates the subject from its object too much. For example, the notion of God which it can construct does not replace the feeling of participation in the divine”. [56]

I think that accessing, and acting upon, this deeper level of consciousness is the only way that we can break free from modern servitude and debasement.

When we deny the intuition and inspiration we receive from the Whole to which we belong, we are turning our backs on our true potential.

We have to stop being bound by the “scientific” thinking that robs us of the life experience which we were born to enjoy.

We have to soar higher in poetry and metaphor, [57] we have to plunge deeper into the power of “dreams, omens, divinations, hallucinations, and the supernatural” [58] that our ancestors once knew and used.

Like Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960), pictured, we have to open our hearts to “prophetic visions” [59] and “sympathetic magic”. [60]

And even if we do not manage to change this world which is so badly in need of the right kind of change, at least we will have lived, at least we will have been real men and real women.

As Virginia Nicholson writes: “There are people in the world who will not make compromises with life. Their faces are turned like sunflowers towards the source of light, and even when battered and broken they refuse to give in to old age, sorrow, loss, defeat”. [61]

[1] Morris Berman: Against Civilization: The Anthropological Critique of Modernity (2025), p. 104. All subsequent page references are to this work.

[2] p. 103.

[3] p. 32.

[4] p. 28.

[5] p. 28.

[6] p. 32.

[7] p. 36

[8] pp. 35-36.

[9] p. 36.

[10] Ibid.

[11] p. 37.

[12] p. 21.

[13] p. 104.

[14] p. 105.

[15] p. 61. See https://orgrad.wordpress.com/a-z-of-thinkers/william-blake/

[16] pp. 59-60.

[17] p. 78.

[18] p. 91.

[19] John Gray, ‘Unenlightened thinking: Steven Pinker’s embarrassing new book is a feeble sermon for rattled liberals’, New Statesman, 22 February 2018, cit. p. 92.

[20] p. 92.

[21] pp. xv- xvi.

[22] p. xvi.

[23] p. 5.

[24] p. 7.

[25] p. 76.

[26] p. 87.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Marshall Sahlins, Stone Age Economics, cit. p. 87.

[29] p. 88.

[30] p. 92.

[31] Pierre Clastres, ‘Exchange and Power’, cit. p. 95.

[32] pp. 96-97.

[33] p. 101.

[34] Augusto Gayubas, ‘Pierre Clastres and societies against the State’, Germinal. Journal of Libertarian Studies, no 9 (January-June 2012), reprinted at acracia.org, cit. p. 101.

[35] p. 100.

[36] p. 101.

[37] Paul Cudenec, The Withway: calling us home (2022), https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/the-withway-paul-cudenec.pdf

[38] p. 3.

[39] pp. 11-12.

[40] p. 12.

[41] p. 14.

[42] Ibid.

[43] p. 15.

[44] p. 19.

[45] p. 93.

[46] p. 25.

[47] p. 54.

[48] Ibid.

[49] pp. 53-54.

[50] pp. 76-77.

[51] p. 77.

[52] p. 78.

[53] p. xvii.

[54] Ibid.

[55] p. 3.

[56] Jean Cazeneuve, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, cit. p. 1.

[57] pp. 52-53.

[58] p. 3.

[59] p. 66.

[60] p. 68.

[61] Virginia Nicholson, Among the Bohemians, cit. p. 73.

Who were allowed to publish, and preach, and teach, unless they were approved? Big Mouths get heard, right? Our problem today is brain washing, long periods of mind control.

LikeLike

Bateson & Mead were married.

LikeLike

Yes, for about 15 years if I recall correctly. Berman does mention it, in fact, but this detail didn’t make its way into my review…

LikeLike