by Paul Cudenec (who reads the article here)

After weeks of reading and writing about psychopaths in power, child murderers and industrial imperialists, I was badly in need of a change of cultural atmosphere.

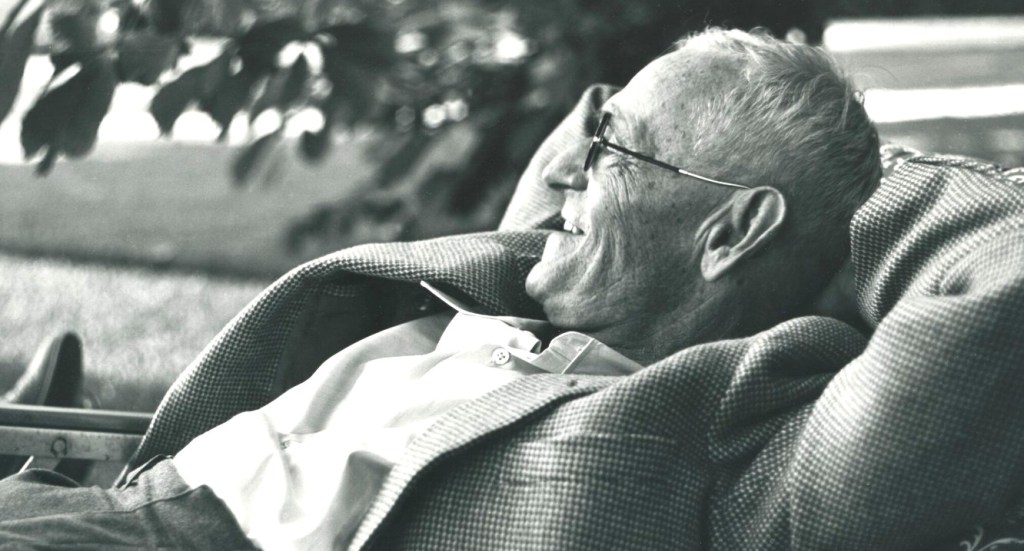

So I was delighted, while visiting the local puces (flea market) to come across a book, that I hadn’t read, by Hermann Hesse (1877-1962), a personal favourite whom I awarded an early place in the Organic Radicals hall of fame. [1]

As it turns out, Enfance d’un magicien (‘Childhood of a magician’) is not what you might call a proper Hesse book, being a collection of short texts culled and translated from various German-language compilations (Traumfährte, Schön ist die Jugend, Prosa aus dem Nachlass and Diesseits – Kleine Welt – Fabulierbuch).

And these scraps of his literary output hardly compare to his major works such as Steppenwolf, Siddhartha, Demian and his masterpiece The Glass Bead Game.

But it was still a pleasure to hear Hesse’s voice in my head again, after an absence of several years, and, as usual, he gave me plenty of food for thought.

He writes, for instance, about the horrors of dealing with bureaucrats, those enforcers of our supposedly obligatory obedience to Leviathan’s Law, [2] now being replaced in their roles by an intelligence even more artificial than their own.

“Anyone who wants to move house, or get married, or obtain a passport or civil status document, arrives at the centre of this hell, spending painful hours in this airless bureaucratic kingdom, interrogated by sad individuals who are simultaneously irritated and in a hurry, who are there to put you in your place, to counter with their scepticism your most simple and honest declarations, treating you as if you were a schoolchild or a criminal”. [3]

He describes the difficulty in submitting to the rules of the society in which he found himself living.

“I, who am as gentle as a lamb and as docile as a soap bubble, showed myself, especially during my youth, to be constantly resistant to any kind of command. As soon as I heard the words ‘you must’, everything inside me bristled and I became stubborn”. [4]

No doubt many readers feel the same way and I would say that a healthy human being knows in his or her heart that self-fulfilment in life depends on being oneself, following only the orders that come from one’s own heart.

While sometimes this instinctive “no!” can come across as exaggerated or unreasonable, I would say that it is a necessary self-protection of our own integrity and potential.

We become our true selves as much as by intuitively rejecting what is not right for us as by having some definite path in mind.

Hesse tells how, as a lad, he wanted nothing more than to be a poet.

This made me smile as, when I was at school, we had to fill in some kind of multiple-choice form which was then analysed, using what at that time (circa 1979) was no doubt very innovative computer technology, to find out what “career” we should be targeting.

I still remember the disconcerted look on the teacher’s face when he read out the first choice that the computer had made for me.

“Poet? That’s not a career! What’s the second one…? Writer? No, that won’t do either! And after that? Journalist. Ah, now that’s possible, at least…”

Hesse’s desire to become a poet was similarly ill-viewed by those tasked to “educate” him.

“It was exactly the same for the poet as it was for the hero and, in general, for all beings and enterprises beyond the ordinary and which spoke of strength, beauty and nobility.

“So long as it was a matter of the past, this was found to be magnificent – there was not a single school textbook which was not full of praise for these exceptional individuals and their endeavours.

“But if it was a question of the present, and of reality, then they were hated and it is possible that the schoolmasters were specifically trained and employed to prevent, as far as possible, a generous and free kind of man from appearing in society and the greatest and most magnificent acts from taking place”. [5]

Despite such disparagement, Hesse relatively quickly found a place in German society as a writer and poet, until disaster struck with the advent of the First World War.

The hysterical reaction to his mild criticism of his country’s participation will be familiar to all those who, for example, called out the Covid scam – part of the same series of shock-and-awe “reset” events, in fact, as I have previously written. [6]

Hesse was essentially “cancelled” – he was labelled a “traitor”, people he considered close failed to speak up for him and old friends cut off all contact, declaring him a “degenerate”. [7]

He was besieged with hate mail and bookshops refused to stock his work.

“I saw myself again in conflict with a world which had let me live in peace up until this point…

“Once more, I discovered a frightening abyss between reality and that which seemed to me to be desirable, reasonable and good”. [8]

I have written before about this gulf between the world that we were meant to be born into – one guided by the values in our hearts that are shared by our kith and kin – and the reality of the modern world under dictatorial imperial occupation, based on grotesque anti-values completely alien to us.

Hesse once declared: “I don’t believe in our politics, our way of thinking, believing, amusing ourselves; I don’t share a single one of the ideals of our age” [9] and in this collection of writing he confirms: “At no point was I a ‘modern man'”. [10]

Much of his life’s activities, including his writing, thus involved an attempted escape from grey sterility into an elsewhere that was surely not entirely inaccessible.

He writes: “I think that reality is something which we should be least concerned about, for it is already boring enough with its continual presence, while much more beautiful and necessary things demand our care and attention”. [11]

Hesse’s work pulsates with the yearning for an enchanted transportation into another world, another plane – and away from all the contemporary sterility.

“We have no other means of changing this ever-disappointing, pathetic and sinister reality than by denying its existence and showing that we are stronger than it”. [12]

An essential source for this strength can be found in days and years gone by, he writes.

“In the cultural realm, an existence based only on the present and the novelties of the day is an unbearable nonsense, for the life of the spirit has a fundamental need to refer constantly to the past, to history, to ancient and primitive realities”. [13]

He sees, quite accurately in my view, the cultural decline of our societies as having been ongoing for many centuries now.

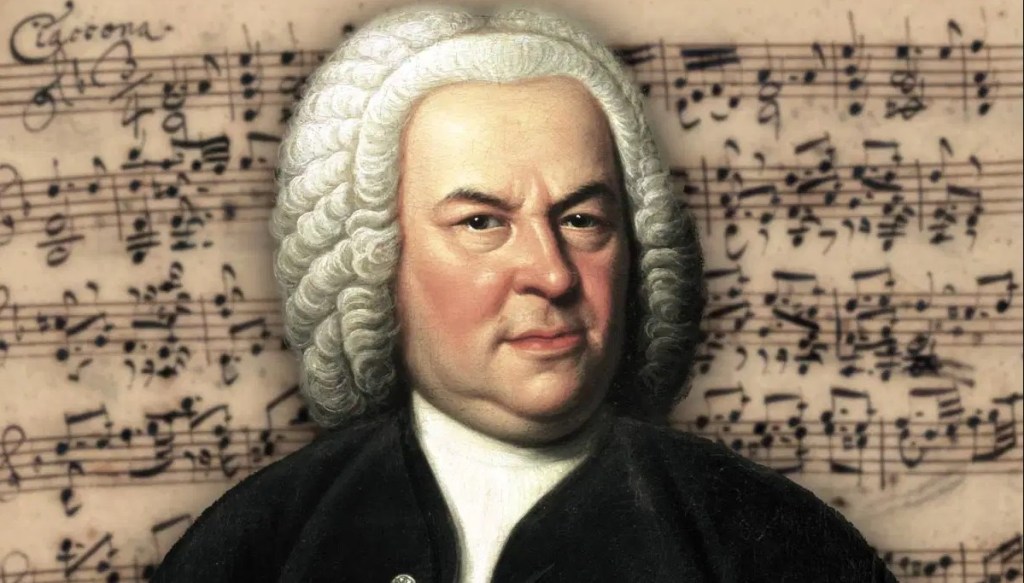

In a story set in the early 18th century, Hesse has his central character, Knecht, describe the music of his time.

“I have to admit that in our epoch it has seen some surprising and suggestive innovations and that, nevertheless, it has, on the whole, lost the purity, rigour and nobility of the old masters, while achieving a new power of seduction not without frivolity and immoderation”. [14]

“There currently reigns across the world a very different spirit and I think that previously, sixty or more years ago, music was better and more scrupulously cultivated than it is at present, for it has become rare to hear in the streets, or in the fields, songs with several melodic lines and in many regions songs with two parts are already the exception”. [15]

But, despite the relentless advance of the dark and drab clouds of modernity we see, from time to time across the centuries, reminders of the eternal existence of truth and beauty breaking through the gloom and shining renewed hope into our souls.

Hesse imagines that same character coming across the work of Johann Sebastian Bach for the first time.

“Very late, when he is no longer young, an echo of Bach’s music reaches his ears; an organist plays some preludes for him. From then on, he ‘knows’ what he has been searching for throughout his life.

“His colleague has also heard the St John Passion, tells him about it, and plays a few passages; Knecht gets hold of some extracts from this work.

“He notes this: despite all its doctrinal disputes, Christianity has managed to express itself once more in a new and admirable way, it has become light and harmony”. [16]

I am convinced, thanks partly to Bach’s works and other sacred music, but also thanks to the spiritual beauty of Gothic cathedrals across Europe, not to forget the words and actions of many contemporary Christians fighting the same battles as I am, that Christianity can act as the channel for the manifestation of all that is best in humanity.

Unlike some Christians, though, I don’t think it is uniquely capable of performing this role – and the monopolistic refusal of this broader truth is one of the factors which has limited and indeed often reversed the positive impact of the religion which was followed by my ancestors for dozens of generations.

As we have seen, Hesse’s yearning for elsewhere often takes the form of a nostalgia for elsewhen.

This is evident on two levels when his 18th century character Knecht, already a projection of Hesse’s historical nostalgia, speaks of his personal attachment to times past.

“All along the road along which God has led me, this period of my childhood has always seemed to me a paradise which I left behind, to which it would have been lovely to return but to which the path and the key have been lost and the door closed – a door which only death will perhaps re-open”. [17]

Writing directly of his own childhood, Hesse (pictured) says: “Yes, for a long time I lived in Paradise”. [18]

Ultimately, I don’t think that Hesse’s evocation of past times is just nostalgia for his childhood or for pre-modern times when the world was still filled with magic.

I think it is, rather, a yearning for that world that he (and all of us) were meant to have been born into, in which we would have found our place, fulfilled our individual potential, in the bosom of a community inspired by our shared values, tastes and desires.

We are looking at an archetype, the projection of the type of world he needed to find in order to flourish and belong.

It is the same Sacred World of which I write in my recent book of that name, one in which we feel our withness to nature as a kind of magic, manifest in certain spirits or gods that lie beyond the flatness of current “reality”.

Hesse writes of his own early paradisical years: “I learned the basics of what we must know in life before starting school, thanks to the teaching given to me by the fruit trees, the rain and the sun, the rivers and the forests, the bees and the beetles, not to mention the lessons of the god Pan and the dancing idols who lived in my grandfather’s cupboard of treasures”. [19]

Describing an ambitious and abandoned project to compose an opera, he explains: “The oscillation of the life between these two poles, nature and the spirit, would have appeared as something as beautiful, as seductive and as complete as the tension of a rainbow”. [20]

As a child, Hesse felt protected in this world by a “little man” who led him on the right path and whom he felt he had always to obey.

“One day he took my hand from something I was about to eat, he led me to the place where I could regain possession of something I had lost”. [21]

I would see this figure as one of the representatives of the natural and cosmic entity to which we all belong, a channel for the guidance we receive from that Oneness if we are open to it, much like the nature-spirit fairies and dancing spiders that I described in Our Sacred World.

Unfortunately, as Hesse grew up, the little man’s appearances become increasingly rare, until he came no more: “In every place, I saw the world become disenchanted around me”. [22]

Although, in this industrial age, where all is defiled, defaced and desecrated, the enchanted world of our hearts no longer forms part of the dull “reality” around us, this does not mean that it does not exist.

It exists, firstly, as a vision, an inspiration, a Holy Grail to lead us into the future. It is a dream calling out to us – through the induced sleep of our servitude – to pay heed, to wake up and to follow its light.

This other world also exists as a potential future, a possibility that can become real if enough of us will it to be so and, as such, it actually already exists in the magical realm of timelessness to which Hesse takes us in his writing.

He muses: “If so-called reality does not play a very important role for me, this is because very often the past appears to me in its fullness as if it were the present, while the present moment can seem incredibly distant in time, to the point that, unlike most people, I cannot make any clear distinction between the past and the future”. [23]

[1] https://orgrad.wordpress.com/a-z-of-thinkers/hermann-hesse/

[2] https://winteroak.org.uk/2025/11/04/leviathans-law-and-the-occupation-of-our-lands/

[3] Hermann Hesse, Enfance d’un magicien, traduit de l’allemand par Edmond Beaujon (Paris: Presses Pocket, 1986), p. 65. All translations from the French are my own and all subsequent page references are to this work, unless otherwise stated.

[4] p. 41.

[5] pp. 44-45.

[6] https://winteroak.org.uk/2024/06/10/wars-resets-and-the-global-criminocracy/

[7] p. 50.

[8] p. 51.

[9] ‘Introduction’, Hermann Hesse, Pictor’s Metamorphoses and Other Fantasies, trans. Rika Lesser (London: Jonathan Cape, 1982), p. vii.

[10] p. 61.

[11] p. 58.

[12] p. 59.

[13] p. 47.

[14] p. 128.

[15] p. 137.

[16] pp. 125-26.

[17] p. 137-138.

[18] p. 17.

[19] p. 14.

[20] p. 62.

[21] p. 26.

[22] p. 38.

[23] p. 59.