W.D. James continues his Faded Republic series with a seasonal film recommendation

There is a stealth republic.

For aficionados of low budget horror movies such as myself, Night of the Living Dead has to be among the best of the best.

(Note: this essay contains spoilers throughout).

George A. Romero’s 1968 cult classic was made for a little over $100,000 using ‘guerrilla filmmaking techniques’ (low budget, minimalist equipment, as few people on the crew as possible) and rises to the level of cinematic art. Any number of frames represent the height of photographic imagery (hence, the release of a ‘colorized’ version in 2023 was completely misguided).

While not the first zombie film (the undead are actually called ‘ghouls’ here), it initiates the modern genre of zombie flicks from which all others take off. The movie can be read in a number of ways, but it is clearly meant to be social and political commentary as well as just good horror. It is in that way that I’ll approach it.

Zombies

‘Yeah, they’re dead. They’re all messed up.’ –Sheriff McClelland.

Zombies are people that aren’t people anymore. They have reverted to nature.

Now, I talk a lot about Nature. By that I usually mean something like Aristotle’s physis. On that conception, Nature is comprised of natures (each species having its own particular nature). Each of these natures strives to perfect itself. I do believe in that. Viewed from this angle, Nature is something like Providence or Gaia.

However, Nature is not all the creatures getting together to sing Kum By Yah. Nature is also, factually, ‘red in tooth and claw.’ That quote is still sometimes misattributed to Darwin and more frequently to Herbert Spencer, but I think it actually originates with the poet Alfred Lord Tennyson:

Who trusted God was love indeed

And love Creation’s final law

Tho’ Nature, red in tooth and claw

With ravine, shriek’d against his creed

Basically, every living thing lives by eating some other living thing. Nature is a slaughterhouse. Both conceptions can be true, and I think they are. Romero’s ghouls are red from head to toe from gorging on their victims.

Zombies, or ghouls, might represent many things. At least one of the things, in Night of the Living Dead, is they become a stand-in for nature overall: it’s out to get us, just as it’s out to get everything. Zombies are ex-people who have become lifeless, free of conscience, mechanical, and who have an insatiable lust for human flesh.

‘They’re coming to get you Barbara’ – Johnny, joking, before he realizes the lumbering man in the cemetery is in fact a zombie out to get them.

In the film a group of seven people find themselves thrown together by circumstance, hiding in a house from the zombies. There is Barbara, a young woman whose brother has just been killed by the zombies. She varies between catatonic and hysterical throughout the whole film; a representative of pure irrationality. Then there is Ben, the hero of the film. Ben is calm and self-composed. There are Tom and Judy, a young dating couple. Tom works for Harry Cooper, a middle-aged business man. The troop is rounded out by Harry’s wife, Helen, and their injured daughter Karen. Karen is the threat within: she has been bitten by a zombie before arriving at the house.

Hobbes

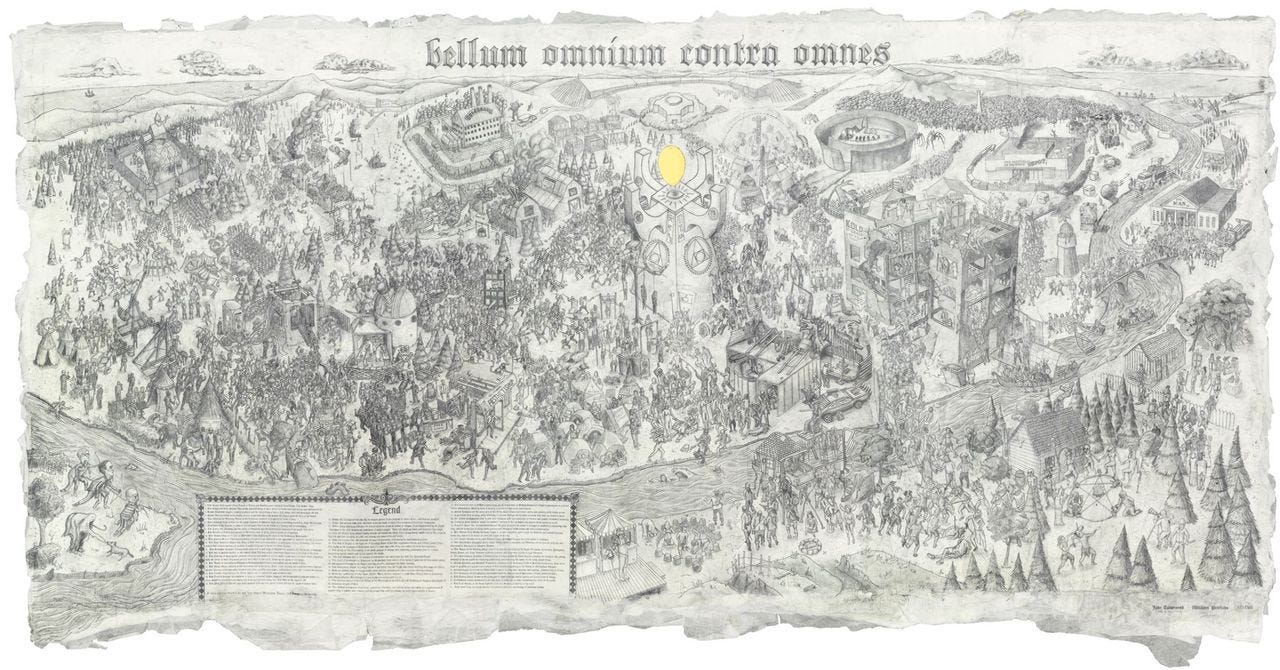

With the zombies representing nature, the little house with its assembled personages is a representation of Thomas Hobbes’ ‘state of nature.’ Like that theoretical construct, the lives of these folks is a war of all against all: the zombies from the outside and each other on the inside unless they can find a way to pull together. Here we come to the question of human nature specifically.

You can simply look at the film as a Hobbesian meditation on the problem of human cooperation and sociality. However, though it starts from the Hobbesian set up, it quickly becomes a critique of that philosophy.

On Hobbes’ account, rational actors will quickly move to form ‘the social contract’, setting up the great Leviathan (the State) to reduce their wills to one in the form of the Sovereign. Authoritarian rule is rational and is what is required to get us out of the state of nature.

However, in the film, the people never manage to form the social contract. Ben is the most rational and sees how his self-interest would be served by working as part of the group. Barbara is in such a state that she can’t agree to anything. Tom and Judy are goodhearted and realize Ben is right and out of a sense of solidarity cooperate with him. The zombie infected daughter is not a party to the negotiations. Helen seems pretty decent, but Harry is the issue.

The usual reading is that he is the bad guy and Ben is the good guy. That’s not really wrong, but I think Romero means to show us that they don’t start from the same position. Ben is very much like Hobbes’ hypothetical rational, acquisitive, individualistic actor. Harry however has a spouse and an injured child. This throws off his calculations (from Hobbes’ perspective). He’s an actual person, like all of us, imbedded in various relationships that are important to us. Harry has already formed a society, his family, so he is more conflicted about the possible payoff of forming a larger society in which the little platoon of his family becomes just three more members.

Basically, the people in this state of nature are never able to form a social contract and they fall prey to the zombies or explosions or being murdered, one by one, until only Ben is left in the morning. Possibly an even more pessimistic view of the human situation than that of Hobbes.

The Sheriff

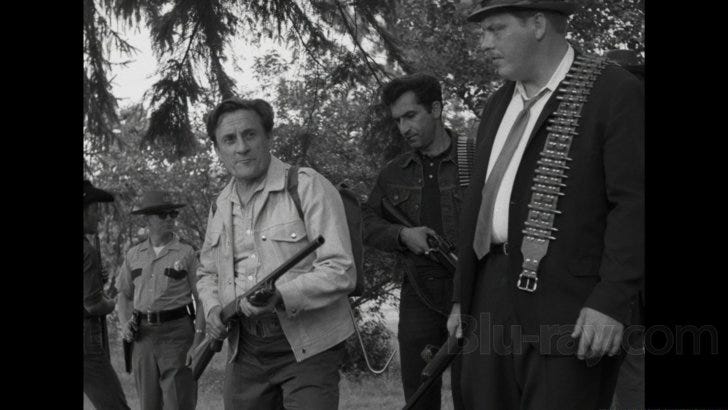

But the assembly in the besieged house is not the only model of human sociality that the film explores. There is also the Sheriff and his posse. I think this is the stealth republic lurking in Romero’s film and in a way in America itself.

I’m going to guess that for many of my readers the idea that a cop can count as the good guy is odd, unless you’re irremediably duped by statist ideology or something. But I don’t think it’s that simple.

In the U.S., Sheriffs usually represent the law enforcement for one county (along with their deputies). In Butler County, Pennsylvania (just north of Pittsburg), where the film takes place, the Sheriff is named McClelland.

Posse Comitatus

The doctrine of posse comitatus derives from the English Common Law tradition. Literally it means ‘power of the county.’ In England, counties are usually called shires and it is worth noting that in J.R.R. Tolkien’s view of The Shire in his Lord of the Rings books, the Sheriffs (also referred to there as ‘Watchers,’ as one of their main duties is to watch the borders of their homeland) is about the only public office that exists in the basically anarchist land of Hobbits. In the Common Law the Sheriff is the main official in the county and they can assemble and arm the citizens of the shire to maintain peaceable order in times of emergency.

Hence, in theory, counties are self-contained and self-sufficient political entities (about the right size I’d say). To get at why this is important, and it is one of the elements that played into the development of civic republican political theory, let’s see what this power of the county is supposed to do.

In 1879, the Congress of the United States instituted The Posse Comitatus Act. What that is supposed to do is limit the use of the U.S. military in domestic police activity. It’s to put the brunt of policing in the hands of the local people and avoid the tyrannical use of the military domestically.

So, the basic principles here are that law enforcement (government) is meant to be very local, to preserve local liberties, and that it trusts in the local citizenry (the posse) to be capable of handling its own business. In fact, there is a radical Sheriff’s association in the U.S. that claims that the county Sherrif is the fundamentally legitimate level of political authority and that in some circumstances they are more legitimate than state or national entities and can rightfully refuse to comply with orders from higher up. (As a side note, some of the various speculations about how a hot civil war could start in the United States hypothesize one of these ‘Constitutional Sheriffs’ facing off against federal law enforcement in defense of locals).

So, the posse is the citizens in arms taking care of their own local peace-keeping needs. While life in the house, the Hobbesian state of nature, is precarious and bloody, Sheriff McClelland and his boys are having no problem ambling through the county destroying zombies left and right. These folks are neighbors and they have no trouble taking care of their own safety and security when formed together. In fact, the social contract is always already formed – we exist naturally in community.

American liberty

As noted above, only Ben, the most together of the characters, survives through the night of the living dead till morning.

As he emerges from the basement of the home and goes to look out the window, he is shot by a member of the posse.

That the filmmakers chose to cast the lead star of the film a black man in 1968 was surely no accident. Nor is it that he is presented as the most positive character.

It is frequently noted that the posse seems to be comprised of all rural white guys and they kill the black guy at the end. That is noticeable (and meant to be noticed I think).

Yet, I believe the easy and the popular interpretation of what is going on there is wrong.

There is in fact a history in the U.S. of posses being formed at the local level to carry out racist ‘justice’; lynchings. Is that what Romero is up to here?

I think clearly not. As presented in the film, those outside the house can barely see Ben as he peeks out the window. The Sheriff just assumes the form they see in the shadows is yet another zombie, he states that it is, and then directs one of the citizen deputies to shoot him between the eyes. Which he does.

I think a much more interesting and nuanced point is being made here. The film is recognizing and evoking the racist history, but clearly Ben’s shooting is a tragic accident in this case.

I think what is being presented is the notion described above – that if liberty is to be preserved, the citizens need to mostly handle their own business. However, as citizens and not specialists or experts, that is both subject to abuse (the biases of ordinary folks tainting justice) and simple mistakes.

But in the film, in Butler County, Pennsylvania, it works. Ben’s death is a tragedy, but the citizens get the job done: they put down the zombie apocalypse, saving many lives and restoring peaceable order. Citizen self-rule is messy, but it may be the only safeguard to liberty.

Further, I think there is a yet deeper significance to the Sheriff and his posse. I noted above that zombies had reverted to nature. That is not exactly right. They have moved toward inanimate nature, to that which is without life. They are dead, they are mere matter. Yet, they hunger.

Byung-Chul Han observes that “Undead, death-free life is reified mechanical life. Thus, the goal of immortality can only be achieved at the expense of life.” Han sees our modern emphasis on industrial growth, capital accumulation, and performance maximization all as attempts to gain a sort of immortality, or at least to avoid death, which ironically reduces us ever more to machines, commodities, and entrepreneurs of the self. Put more simply, the more we rely on machines, the more mechanical we have to become in adapting ourselves to them (including adapting our thought to mere computation to accommodate AI); the more focused we are on capital accumulation, the more we see the world as only commodities; the more we come to see ourselves and others exclusively economically, the more we try to perfect ourselves, the more we burn ourselves out.1 The unnatural quest to evade death brings on death, leaving us ‘undead’ while yet living.

If the Sheriff denotes the sort of localized self-sufficiency and liberty that I articulate above, this is then set in direct contrast with the ‘reification of mechanical life.’ The Sheriff and his boys represent an antithesis of that. Unlike in the house, they are not lost in a Hobbesian game of self-interested calculation. They already form a community and, hence, can just go out and kick zombie butt. Life wins.

If you liked this (or, even if you didn’t) check out my previous two Halloween movie recommendations.

2023- Cropsey and Social Horror

Of course, I can’t leave without a bit of music. I suppose this is the too obvious choice.

It’s a cool song and video either way. Could that be Sophia on the cross? Pretty sure that would be hyper orthodox. Christ symbolically gives birth on the cross- go read it (John 19:34). New life after or through death: the anti-zombie.

I can’t say I’m not on the side of the kids learning to dislike the soldiers patrolling their streets though.

Happy Halloween!

Byung-Chul Han, Capitalism and the death drive, Polity, 2021, p. 10.