by Paul Cudenec (who reads the article here)

Over recent centuries we have, as Mircea Eliade points out, witnessed a “gigantic transformation of the World taken on by industrial societies and made possible by the desacralisation of the Cosmos under the effect of scientific thought and, above all, by sensational discoveries in physics and chemistry”. [1]

He underlines the enormous gulf between the traditional and modern ways of living, noting that for Le Corbusier, the notorious Swiss-French pioneer of modern architecture and urban planning, a house was merely a “machine to live in”. [2]

Eliade remarks: “The ideal house in the modern world must be, above all, functional, in other words allowing people to work and to rest so as to be able to work.

“You can change your ‘machine to live in’ as frequently as you change your bike, fridge or car.

“You can also leave the town or province of your birth with no other inconvenience than the changes in the climate that this involves”. [3]

Alongside dehumanising urban planning and “modernisation” came the behavioural psychology required to manufacture human beings who would tolerate modern industrial slavery.

Morris Berman describes how, at the start of the 20th century, American infant care was under the influence of Luther Emmett Holt, Sr, a professor of paediatrics whose popular writings urged fixed feeding schedules, abolition of the cradle, and a minimum of fondling.

“J.B. Watson, the founder of behavioural psychology, was also very influential at this time, and he urged mothers to keep their emotional distance from their children.

“He specifically stated that such treatment, in addition to fixed feeding schedules, strict regimens, and toilet training, would mold the child’s capacities in a manner that would facilitate its conquest of the world”. [4]

Berman notes that Watson’s avowed objective of making the child “as free as possible of sensitivities to people” has now “come to fruition with stunning ‘success'”! [5]

Not long after the publication of his Psychology from the Standpoint of the Behaviorist (1919), Watson accepted a job with an advertising agency in New York, where “he applied his principles for controlling rats to the manipulation of consumers”. [6]

This organised manipulation of human beings, of our ways of thinking and being, has of course not been conducted in the interests of the great majority, but in the interests of those who would dominate and exploit us.

As Berman remarks: “Imperialism, whether economic, psychological, or personal (they tend to go together) seeks to wipe out native cultures, individual ways of life, and diverse ideas – eradicating them in order to substitute a global and homogeneous way of life”. [7]

“Modern science, in short, is the mental framework of a world defined by capital accumulation”. [8]

With this in mind, we need to go back to some of the key players in the imposition of the “scientific” outlook, as described in a recent essay, [9] and see if they were plausibly participants in a pre-meditated plan to reshape our lives, to train us like laboratory rats to think and behave in ways that reap the most profit for a dominant few.

Berman judges: “One thing that is conspicuous about the literature of the Scientific Revolution is that its ideologues were self-conscious about their role.

“Both Bacon and Descartes were aware of the methodological changes taking place, and of the direction in which things would inevitably move.

“They saw themselves as leading the way, even possibly tipping the balance”. [10]

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) himself wrote in 1620: “We must begin anew from the very foundations, unless we would revolve forever in a circle with mean and contemptible progress”. [11]

We see here a direct assault on the natural cyclical time enjoyed in the “static and self-sufficient world” of our ancestors. [12]

People had to be uprooted from their pleasant traditional existences and put to work as human capital on the lucrative treadmill of modern “progress”.

In the light of what Max Weber tells us about the role of Protestant Puritanism in the “disenchantment of the world”, [13] it is interesting to see that Bacon, as a sickly child, was educated at home by “John Walsall, a graduate of Oxford with a strong leaning toward Puritanism” [14] and later travelled abroad with Sir Amias Paulet, the English ambassador in Paris, “a fanatical Puritan with a harsh character”. [15]

It is also intriguing to note that Bacon’s career ended in disgrace when “a parliamentary committee on the administration of the law charged him with 23 separate counts of corruption”. [16]

Wikipedia refers to speculation that his acknowledgement of guilt may have been made because he had “been blackmailed, with a threat to charge him with sodomy, into confession”.

And it suggests that Bacon may have been describing himself when he wrote in his novel New Atlantis about married men who secretly visited “dissolute places” for “meretricious embracement’s (where sin is turned into art)”.

Anyone else thinking of Jeffrey Epstein’s 21st century blackmailing operation?

Historian Paolo Rossi has argued for an occult influence on Bacon’s (pictured) scientific and religious writing.

We learn that “conspiracy theories surrounding Bacon” include alleged connections to the Freemasons and the “Qabalistic” Rosicrucians, famous for their manifestos proclaiming a change agenda. [17]

“In the early 17th century, the manifestos caused excitement throughout Europe by declaring the existence of a secret brotherhood of alchemists and sages who were preparing to transform the arts and sciences, and religious, political, and intellectual landscapes of Europe”, says Wikipedia. [18]

It also emerges that Bacon had borrowed a large amount of money in his younger years and was thus lumbered with debts.

“In 1608 he began working as the Clerk of the Star Chamber. Despite a generous income, old debts still could not be paid”. [19]

It would be fascinating to know to whom he was in debt!

René Descartes (1596-1650) has, coincidentally, also been linked to both Freemasonry and the Rosicrucians. [20]

He even specifically dedicated one of his mathematical projects to the “F.R.C.” (Frères Rose-Croix), whom he described as “very famous” in Germany. [21]

Also very relevant is the fact that Descartes, although a Roman Catholic, served a Protestant state.

“Descartes (pictured) spent much of his working life in the Dutch Republic, initially serving the Dutch States Army, and later becoming a central intellectual of the Dutch Golden Age”. [22]

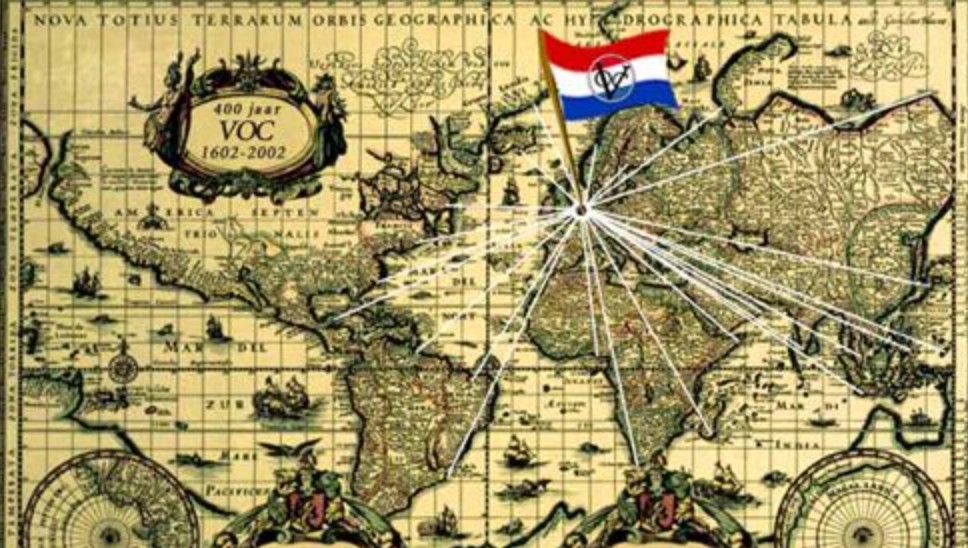

This “golden age” of the Dutch Republic, following its creation in 1602, was the period described by Meeuwis Baaijen, in his 2024 book The Predators Versus The People, as that during which it was the temporary HQ of “Glafia” – the global mafia.

Having moved its centre of operations north from Venice, Glafia was shortly to switch to London, then much later to New York.

Baaijen writes: “While the Dutch and British states were still in diapers, metaphorically speaking, powerful and ruthless private joint stock corporations were given the task of colonization: the British (1600) and the Dutch (1602) ‘multinational’ East India Companies (EIC), mostly owned by Glafia or Glafia-affiliated shareholders”. [23]

“In a letter to Oliver Cromwell, Rabbi Menasseh Ben Israel had bragged about the great influence of the Jews in the Dutch colonial and financial projects”. [24]

Baaijen explains how the Dutch war for independence from Spain had been financed by Glafia from Venice as part of a sidelining of the Catholic state, and its Portuguese neighbour, from their global roles.

This, he argues, “was undoubtedly related to their expulsion of the large numbers of Jews at the end of the 15th century, and more generally, to their anti-capitalist and anti-usury stance.

“That’s why Glafia chose to go ahead with the Protestant (Jew- and usury-friendly) Dutch and Brits”. [25]

As a servant of the Dutch Republic, Descartes was therefore effectively employed by the global industrial-imperialist mafia.

Little surprise that his influential philosophy was such a perfect fit with its life-denying and disenchanting agenda of separation and control!

We have heard how Descartes’ approach is characterised by a “schizoid duality” [26] and Berman identifies something similar regarding Isaac Newton (1643-1727), who took up the Cartesian “scientific” baton in England when it, in turn, had become the global mafia’s HQ.

“Despite his eventual nervous breakdown, Newton was no psychotic; but that he bordered on a type of madness and allayed it with a totally death-oriented view of nature, is beyond doubt.

“What is significant, however, is not his view of nature itself, but the broad agreement that it found, the excitement that it generated.

“Newton was the magician who succeeded. Instead of remaining some kind of isolated crank, he was able to get all of Europe ‘to join in the grand obsessive design’, becoming president of the Royal Society and being buried, in 1727, amidst pomp and glory in Westminster Abbey in what was literally an international event.

“With the acceptance of the Newtonian world view, it might be argued, Europe went collectively out of its mind”. [27]

I don’t think it is irrelevant that in 1696 Newton moved to London to become master of The Royal Mint, four years after it introduced “new production methods” for manufacturing money. [28]

Berman identifies a strange shift in Newton’s interests, from a focus on alchemy and nature-based Hermeticism to his role as “a mechanical philosopher”. [29]

He maintains that this change was not made on scientific grounds, but political ones and that we should bear in mind the society in which he was trying to establish his place.

“The forces that triumphed in the second half of the seventeenth century were those of bourgeois ideology and laissez-faire capitalism.

“Not only was the idea of living matter heresy to such groups; it was also economically inconvenient.

“A dead earth ruptures the delicate ecological balance that was maintained in the alchemical tradition, but if nature is dead, there are no restraints on exploiting it for profit.

“Loving cultivation becomes rape; and that, to me, is most clearly what industrial society in general (not just capitalism) represents”. [30]

Newton (pictured) was also, from 1703 until his death in 1727, president of The Royal Society, fully named The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. [31]

The period around its creation in 1660 is a crucial one in understanding the origins and purpose of the “scientific” thinking behind global industrialism and imperialism.

Berman writes of “a general ‘congruence’ between science and capitalism in early modern Europe”.

He adds: “The rise of linear time and mechanical thinking, the equating of time with money and the clock with the world order, were parts of the same transformation, and each part helped to reinforce the others”. [32]

He also reveals that a deliberate and co-ordinated offensive to introduce this new way of thinking was already underway by the middle of the 17th century.

One important figure at this time was French polymath Marin Mersenne (1588-1648), who joined the Minim Friars in 1611 and, after studying theology and Hebrew in Paris, was ordained a priest in 1613. [33]

“Mersenne’s monastic cell became the virtual nerve center of European science. He conducted weekly meetings and a vast correspondence with scientists in every country, introducing their works to each other and to the educated public.

“Proponents of mechanism, such as Galileo, were translated or explicated. Contacts were made with men who would later be key figures in the Royal Society of London, and these ties were strengthened when a number of them went into exile in Paris during the Civil War”. [34]

“The mechanical philosophy, and the divorce of fact from value, were built right into the guidelines of the Royal Society”. [35]

A whiff of conspiracy surrounding the Royal Society is provided by the very name of the informal group which paved the way for its creation.

From 1630, members of the “Invisible College” devoted themselves to the cultivation of the “new philosophy” and met frequently in London, often at Gresham College, with meetings also held at Oxford. [36]

This influential group was also known as the “Hartlib circle”, after Samuel Hartlib (1600-1662) a Polish-born follower of Bacon’s work who has been called “the Great Intelligencer of Europe” – intelligencer being defined as “a bringer of intelligence (news, information); a spy or informant”. [37]

Professor Yosef Kaplan of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem provides some very enlightening information about Hartlib (pictured) and his activities in his essay ‘Jews and Judaism in the Hartlib Circle’. [38]

He writes of “the connections that Hartlib and his partners formed with Jews from Holland and other places, from at least 1650 until his death in 1669”. [39]

He says that the wealthy Amsterdam merchant and theologian Petrus Serrarius “transmitted important information to Hartlib and [John] Dury about the disposition of the Jews of Amsterdam, especially at the time of the Sabbatean messianic fervour that set the entire Jewish world in an uproar in 1665-1667, and also gleaned information from the Levant about the ‘messiah’ Shabetai Zevi and the echoes aroused among both Jews and Christians about his actions, including his conversion to Islam”. [40]

This pragmatic and false “conversion”, by the way, is considered by some Jews to provide moral justification for the practice of hiding their real faith behind the cloak of a different religious identity. [41]

Kaplan continues: “Taking note of the rather marginal concern with Jewish matters on the part of Hartlib and his associates until the early 1640s, the great importance that they bestowed upon the subject of the Jews in their educational plans, at least from 1642 on, is striking”. [42]

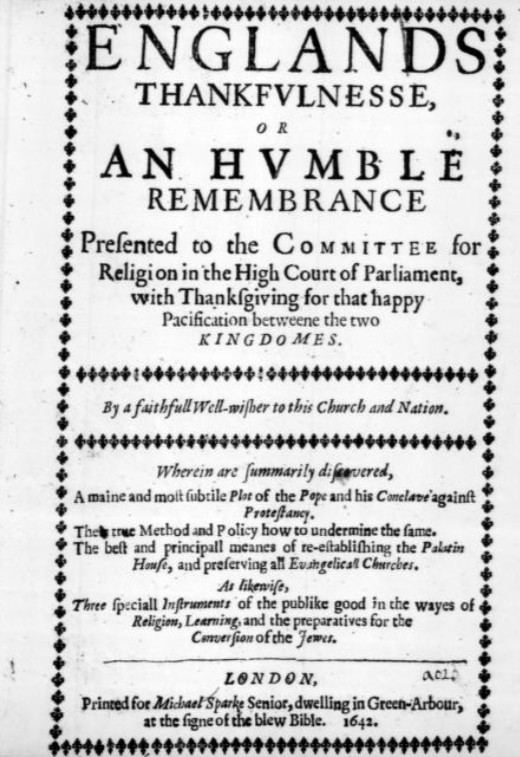

In that year, he explains, Hartlib published a document entitled Englands Thankfulnesse.

Here, the task of bringing the Jews to “true conversion” to Christianity was presented as one of the most important aims of the Protestant camp and indeed of the English people, along with the efforts to reform education and, of course, to advance science.

To realise God’s kingdom, Protestants were needed to bring the Jews into the bosom of Christ, “because none are fit to deale with them to bring them to Christ, but Protestants”.

However, in order to pave the way for the conversion of the Jews, which was prophesied in the Book of Daniel and in Revelations, Hartlib argued it was necessary “to make Christianity lesse offensive, and more knowne unto the Jewes, then [sic] now it is, and the Jewish State and Religion as now it standeth more knowne unto Christians”.

Protestants therefore had “to perfect within themselves that part of knowledge and learning, which is necessary to prepare a way for their conversion”.

Kaplan says Hartlib and Dury based their view of the place of the Jews in the millenary age on the English Protestant apocalyptic tradition which, from the time of John Bale on, made the Jew into a “glorious apocalyptic agent”, in stark contrast to Martin Luther’s opinion that the Jews were destined, along with the Antichrist, Satan, and Gog and Magog, to be objects of the wrath of God. [43]

He adds: “Hartlib and Dury drew freely upon [Thomas] Brightman’s apocalyptic teachings, which led to a radical rehabilitation of the Jews, as having to fulfill an actual historical function in salvation history”. [44]

Kaplan notes that quite a few of Hartlib’s correspondents in Holland, who included Johannes Moriaen, Justianus van Assche, Godofroid Horton and the aforementioned Petrus Serrarius, were especially interested in Jewish studies. [45]

“Hartlib and Dury began to sketch proposals for the establishment of a Federative University in London, one of whose colleges was to concentrate on Jewish studies”. [46]

“The names of Boreel, Ravius and even of Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel were mentioned as possible candidates for teaching posts in that proposed institution, but I doubt whether the Sephardic rabbi of Amsterdam was involved in any way in this plan or that he knew about it at that stage”. [47]

“Just as the college ‘towards the advancement of Universal learning’ was intended to help people become more rational, so, too, the college for the study of ‘Oriental tongues and Jewish Mysteries’ was intended to make people more ‘pious’, since the ‘first oracles of God’ were delivered in those languages, and the revelation of the true worship and religion was transmitted to humanity by means of Judaism”. [48]

It is noteworthy how the idea of making people “more rational” is so closely linked here with the idea of “true” religion originating from Judaism.

We see a reflection of Berman’s statement that the Jewish religion was “based precisely on the rooting out of animistic beliefs” [49] – in other words our sense of belonging to living nature.

I am also reminded of Alain Daniélou’s reference to “a Judaism which had become monotheistic, dry, ritualistic, puritan, Pharisee and inhuman” [50] and of John Lamb Lash’s view that the ancient Jews were not interested in conscience, and the power to choose what is right, but “merely introduced a set of rules purporting to dictate what is right”. [51]

It is further worth recalling that Max Weber says Judaism has a “particular historical importance in the blooming of the economic ethics of the modern West”. [52]

We see clearly here the basis of the scientific “rationality” so central to the supposedly “new” philosophy being promoted by Hartlib and his friends.

In the end they did not create the college they had in mind, but, explains Kaplan, “at the same time, they did not miss any opportunity that came their way to encourage cooperation with others, both Jewish and Christian, in publishing the basic texts of Judaism.

“The point of departure for their approach was recognition that a considerable portion of the Jews of Western Europe, and especially of the Dutch Republic, with whom they had direct or indirect contact, themselves lacked sufficient knowledge of their Jewish heritage”. [53]

A more direct aspect of the Invisible College’s work involved “the desire of Hartlib and Dury to work for the Jews’ return to England”. [54]

Kaplan says the two most prominent Jews who maintained “close and long-standing ties with the Hartlib circle” were Jacob Judah Leon and Menasseh ben Israel. [55]

The latter, who, as we heard, boasted about the great influence of the Jews in the Dutch colonial and financial projects, played a key role in planning the (official) return of Jews to England under Cromwell, victor of the Civil War.

Kaplan notes with regard to the Hartlib circle: “The help they extended to Menasseh ben Israel in his mission to Cromwell in 1655 is well known and described at length and in great detail in many studies”. [56]

Their all-round philo-semitism had long-term consequences that spread beyond Britain’s shores, he adds, and “contributed significantly to a change in attitudes toward the Jews in early modern Europe”. [57]

“The Protestant millenarians in the Hartlib circle were respectful and sympathetic to the idea that the Jews had been God’s chosen people, and they even foresaw a great future for their ‘elder brethren'”. [58]

But why was it so important to engineer the open return of Jews to England, nearly 400 years after they had been expelled by King Edward I (pictured)?

Despite a thin veneer of religious justification, the real reason was clearly the rich pickings on offer from rapidly expanding British commerce and imperialism, including, of course, the slave trade.

Wikipedia tells us that Cromwell “foresaw the importance for English commerce of the participation of the Jewish merchant princes, some of whom had already made their way to London”. [59]

So what exactly is staring us in the face here?

A deliberate initiative to destroy the traditional nature-rooted spirituality and ethics of whole populations in order to turn them into submissive and disempowered fodder for the industrial-imperialist money machine?

And this carefully planned intergenerational “modernisation” [60] project – the manufacture of a “world defined by capital accumulation” – being grounded in a belief in the supremacy of Judaism, its “rational” ways of thinking and its “chosen people”?

Is it possible to name what we see, without being regarded as dangerously deluded by contemporary society?

The irony, of course, is that modern inversion means that today sanity is often mistaken for insanity and vice versa.

Berman comments that “we now live in a world turned upside down, a systemic double bind that has resulted in a kind of collective madness”. [61]

And he cites R.D. Laing’s summary of that double bind: “Rule A: Don’t. Rule A.1: Rule A does not exist. Rule A.2: Do not discuss the existence or nonexistence of Rules A, A.1 or A.2”. [62]

[1] Mircea Eliade, Le sacré et le profane (Paris: Gallimard, 1987), p. 50. All translations from French in this essay are my own.

[2] Eliade, p. 49.

[3] Eliade, pp. 49-50.

[4] Morris Berman, The Reenchantment of the World (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1981), pp. 168-69.

[5] Berman, p. 169.

[6] Philip J. Pauly, ‘Psychology at Hopkins’, Johns Hopkins Magazine 30 (December 1979), p. 4O, cit. Berman, p. 326.

[7] Berman, p. 263.

[8] Berman, p. 49.

[9] Paul Cudenec, ‘The “scientific” war on our freedom’. https://winteroak.org.uk/2025/08/08/the-scientific-war-on-our-freedom/

[10] Berman, p. 29.

[11] Francis Bacon, New Organon, Book 1, Aphorism XXXI, in Hugh Dick, ed, Selected Writings of Francis Bacon (New York: The Modern Library, 1955), cit. Berman, p. 29.

[12] Berman, p. 52.

[13] Paul Cudenec, ‘The disenchantment of life’. https://winteroak.org.uk/2025/08/01/the-disenchantment-of-life/

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amias_Paulet

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon

[17] Ibid.

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosicrucianism

[19] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon

[20] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ren%C3%A9_Descartes

[21] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ren%C3%A9_Descartes

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ren%C3%A9_Descartes

[23] Meeuwis T. Baaijen, The Predators Versus The People: The Big Picture of the 500-year Secret War against Humanity and how to regain Our Stolen Planet, Freedom and Future (San José, Costa Rica: 2024), p. 59. https://thepredatorsversusthepeople.substack.com/

[24] Baaijen, p. 54.

[25] Baaijen, p. 78.

[26] Berman, p. 35. See Cudenec, ‘The “scientific” war on our freedom’.

[27] Berman, p. 121.

[28] Berman, p. 21.

https://www.royalmint.com/brand/our-story/1400-1800/

[29] Berman, p. 122.

[30] Berman, p. 126.

[31] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Society

[32] Berman, p. 57.

[33] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marin_Mersenne

[34] Berman, p. 111.

[35] Ibid.

[36] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Boyle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Invisible_College

[37] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Hartlib

Arved Hübler, Peter Linde and John W. T. Smith, Electronic Publishing ’01: 2001 in the Digital Publishing Odyssey (IOS Press, 2001).

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/intelligencer

[38] Yosef Kaplan, ‘Jews and Judaism in the Hartlib Circle’, Studia Rosenthaliana, 2006, pp. 186-215. https://pluto.huji.ac.il/~kaplany/hartlib.pdf

[39] Kaplan, p. 190.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Tobin Owl, ‘Sabbataen-Frankist Illuminism and Labor Zionism’. https://totheroot.substack.com/p/sabbataen-frankist-illuminism-and

[42] Kaplan, p. 190.

[43] Kaplan, pp. 190-91.

[44] Kaplan, p. 191.

[45] Kaplan, p. 193.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Kaplan, p. 194.

[48] Kaplan, p. 195.

[49] Berman, p. 70. See Paul Cudenec, ‘The disgodding of nature and our hearts’. https://winteroak.org.uk/2025/08/08/the-disgodding-of-nature-and-our-hearts/

[50] Alain Daniélou, Shiva et Dionysos: La Religion de la Nature et de l’Eros de la préhistoire à l’avenir (Paris: Fayard, 1979), p. 287. See above essay.

[51] John Lamb Lash, Not In His Image: Gnostic Vision, Sacred Ecology, and the Future of Belief (White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green, 2006), pdf version, p. 228. See same essay as above.

[52] Max Weber, Sociologies des religions, choix d’extraits et traduction Jean-Pierre Grossein (Paris: Gallimard, 1996), p. 331, cit. Max Weber, Sociologie de la religion (‘Economie et société’), traduction de l’allemand, introduction et notes par Isabelle Kalinowski (Paris: Flammarion, 2006), pp. 285-86 FN.

See Cudenec, ‘The Disenchantment of Life’.

[53] Kaplan, p. 195.

[54] Kaplan, p. 206.

[55] Kaplan, p. 196.

[56] Kaplan, p. 206.

[57] Kaplan, p. 209.

[58] Kaplan, p. 210.

[59] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menasseh_Ben_Israel

[60] Paul Cudenec, ‘Modernisation means pillage and profit’. https://winteroakpress.wordpress.com/2025/01/31/modernisation-means-pillage-and-profit/

[61] Berman, p. 233.

[62] E.Z. Friedenberg, R.D. Laing (New York: Viking, 1974), p. 7, cit. Berman, p. 228.

I suspect it goes back to the Romans. Or even before…

LikeLike

This might complete your words on the Global Mafia and its origins

https://members.tripod.com/~american_almanac/contents.htm#venice

LikeLike