Long have divinations about the energies and meanings of our material world been followed and practised. They were part of the ‘philosophia perennis’, the perennial flow of ancient wisdom, man’s great arc of consciousness that spanned the ages, from the elemental gods of old to the threshold of the modern.

* Tough, strong fingers grip a shaft of bamboo. A sinewy arm pulls, and the bamboo shaft, yellowing but with a pallor of green here and there, flexes. Good, says the craftsman to himself, this is the right stem for what he will make. But he looks around him for a few moments. There are other stems in the bamboo grove, taller and thicker, some not so, but with more luxuriant leaf fall around their bases. Those he makes a mental note of; they will be needed for the larger, more ceremonial objects he will be called upon to fashion two moon cycles from now. For the ordinary workaday basket he will create, the stem in his grasp will do.

One more scan with practised eyes across the hillside, just above the village. The grove is healthy enough, the signs of sufficient water are evident. Then a few words spoken, slowly and clearly, for the living bamboo stem to hear, and a pause. Then a deep breath and a machete is swung. Its hardened and sharpened edge slices into the heavy bamboo shaft, but not all the way through. Two more swings and the shaft is severed. Another pause, and another slow sentence, addressed this time to the root clump that remains. The machete is cleaned and stowed, the tall shaft is now seized, settled across one shoulder, and the craftsman begins retracing his steps towards his home.

* One quick skip, and the little streamlet is crossed. On this side, the healer-collector knows, the sunlight falls more evenly through the leafy canopy overhead, and causes the athamanticum bushes to reach higher, their flowers to sport brighter white hues. They are neither scarce nor plentiful in this part of the forest, and although she knows that a mile or so further in what she seeks will be both plentiful and powerful, venturing farther would also be risky, for this is the haunt of the black bear. Expertly wielding her small sickle, she chants softly, almost under her breath, the invocation to the forest mother. The stalks tumble down, one after another, and go into – flower and leaf and stalk, for each will be put to a different use – her woven tache.

Now her footsteps crunch as her heavily sandalled feet crush a light frost that cloaks the forest floor. From here, she knows, the athamanticum must not be taken, for the winter, although retreating, still governs the lowest tier of the forest floor, and any medicinal draught distilled from these bushes will be much weaker than otherwise. But her tache is more than half full already, and she has collected enough and more for her needs (for she has been asked to treat joint and hip ailments). A month hence she will return, and with the promise of warmer weather bringing new vitality to the herbal bushes, she will need two large taches and a helper.

* It takes a few words of coaxing, but only a few, and the brace of oxen step off the bund and into the field. Before them, on the reddish-brown soil, lies the simple wood-and-iron light plough. The oxen know it will be their first work of the season, and in their own mischievous way, feign laziness. But the farmer knows them well. Soon they are yoked up, and from a small bag the farmer brings out a small metal container. This he unscrews and from it, pours out oil into his palm, to smear the metal of the plough. The oil has been consecrated at the temple, and a mantram has been spoken over it.

From a paper packet he then takes ash, turmeric paste and vermilion. These are applied to the foreheads and horns of the oxen. The wood of the plough too is daubed. Next, a handful of incense sticks is lifted out of the bag. Walking barefoot along the perimeter of his field, the farmer places a few of the lit sticks in each corner of the field, to ask the four quarters to bring his field clean fresh air. One last handful of sticks is then poked into the soil next to a small statuette of Ganesha, who sits phlegmatically on a low stool. The farmer utters a shloka, Ganesha listens, then the plough is affixed to the beam. A word to the oxen and they step forward. The brown dust rises, the earth awakes.

These vignettes may seem familiar to the older amongst us, but they are alas no longer as timeless as they were taken to be, not so very long ago. Their actors – the bamboo craftsman, the herbalist-healer, the rice farmer – have always been figures near at hand, if somewhat removed from the bustle of a typical rural society, because of the supersensory abilities they must needs exercise in pursuit of their arts, but nevertheless near and therefore familiar.

These characters were seen and known in our villages. They were a neighbour, the sister of one’s father, a younger uncle. They were both family and repositories of tradition. That familiarity and that closeness waned during the last quarter of the 19th century, dimmed during the first half of the 20th, flickered dull during the last quarter of the 20th century, and faster still during this first quarter of the 21st, which is where we find ourselves now. These characters, and others like them, are not at all now familiar, but strange, as if from a bygone age, remnants of a recent world made suddenly older.

I had known them all, characters like these and others besides, from my youth when dealt the good fortune of having heard and seen them, sojourned through their villages and their hills and crossed their rivers, when their arts still had some remnant of the vitality of old. Recalling how I had seen them then, not once had I in those times been struck by the thought that there could come a time when such characters would not be amongst us, and that there would be no-one to take their places. It would have seemed fanciful, impossible. Yet in the now, some 40 years advanced from the days when my memory was stamped with those people, places, actions, impressions, they may have slipped into that alter-universe we call history, quietly and unnoticed by this the post-modern post-electronic age.

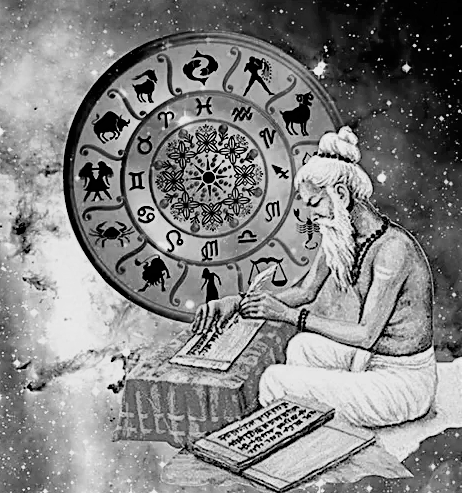

Common to the three characters in these three vignettes is their understanding of the essences and subtleties of nature (so it has come to be called and understood in the European languages – Nature, Die Natur, la Nature, Natura, la Naturaleza – but the layers of meaning that accompany the nature-concept are only infrequently examined). The bamboo craftsman sees the vitality of earth and water as they have come together in the bamboo stem. The healer-collecter can judge the potency of the herb she collects for she possesses the ability to see and smell, in the herb’s form and colours, the presence of radiances gathered therein from moon, sun and other heavenly bodies. The farmer has his calendar to consult, the one that marks for him the seasonal days and the lunar alignments that are propitious for the preparation of the soil, its tilling, for transplanting the rice seedlings. He is able to sense the receptivity of the earth for what he asks her to bear and because of this ability, has the small power to amend the calendar.

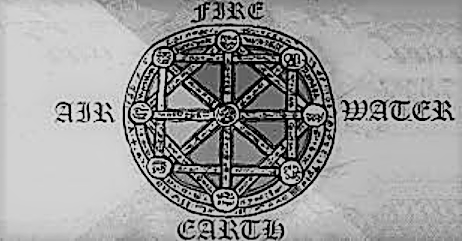

What these characters and those like them know, are in everyday communion with, are the elements. It is these elements – whether enshrined in one or another culture as groups of four or five (four are more common in the Occident, five in the Orient) – whose consideration is the key to the bridge between the material world and consciousness, not individual but (to use a term that has become popularly connected with ‘earth philosophy’ and ‘pantheism’ and similar ideas) earth consciousness. But naturally, given the obsessions of our modern (and post-modern or post-industrial) era with the material, the gross forms of the elements, doing so is very difficult if not close to impossible for a very large section of people. The elements have forms beyond the gross material and their many powers may be discerned at a level only supersensory, far beyond the ordinary limits of our senses, beyond even the reach of many of those who have spent years attuning themselves in order to cross sensory barriers.

Even so, there are to be found, in the groups of people that are (for the sake of typological convenience, given the names of) craftspeople, traditional healers and medicators, cultivators and farmers who follow age-old methods using indigenous seeds and their own calendars, such supersensory capabilities. They are able to ‘see’ the elements beyond their immediate gross forms, to perceive the manner of the elements’ interactions with one another, to compute for each interaction its astrological and cosmological influences, then to take all that they see in such a way and project it forward – for a hand-made object, for a potion, for a grain – through time. They are, in short, closer to the true nature of the elements than any other in this our multiply deranged planetary consumer- and electronic-society of the first quarter of the 21st century.

To understand a lineage like this, we shall have to travel back to ages when supersensory abilities were commonplace. In the western tradition (that is, old Europe and the northern temperate lands and mountainous regions, a region that would correspond to the western uplands of the Urals stretching to the Atlantic coast and upwards into modern-day Scandinavia) there were four principal elements and, flickering through the centuries until the notion became better accepted – thanks to the alchemical writers, a fifth. Our three characters in such a setting (the healer-collector is already there) would then be the woods-craftsman (selecting birch, ash, larch, spruce, beech, poplar, elm, pine and so on instead of bamboo), and the farmer of barley, oats, spelt, einkorn, emmer, rye, roggen.

“Once established, the fourfold system of the elements became the foundation for the western traditions of magick, and also influenced the spirituality of the developing religions … the four elements represent the building blocks of form and the transformative actions of force.” So Rankine and D’Este have written, in their treatise concerning the four elements of the western tradition1. The origins of the four elements can be found in the writings of the pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Empedocles in the fifth century of the common era. In his ‘Tetrasomia’ (or doctrine of the four elements)’, Empedocles explained in the poetic On Nature that the four elements were not only the building blocks of the universe, but also spiritual essences. He equated the sources of the elements to deities, giving divine origins to the elements2.

Empedocles did not create for (what became known as) the Western tradition the system of Four Elements. Many are the texts complete, the texts in fragments and the texts hinted at by newer texts but which appear to have vanished, which transported this sys tem, over the ages, to that of the Greek philosophers. If Empedocles proposed patterns of relationships between Fire, Water, Air, and Earth – what he called “the four roots” – which were in his time and thereafter considered to be fundaments, from which all things came into being, then his was not an original thought. For there is abundant evidence, in the less known, scarcely cited, uncatalogued corpus of literature – the great bulk of it not at all in the scripts of the classical learning canons, that is Latin and Greek, but indeed in every European language that had a script. If in the fourth century BCE Aristotle expounded further on the elements as spiritual essences (concentrating on their qualities in his work De Generatione et Corruptione) then that too was not original. And when a few short decades later, in his Timaeus, Plato postulated a somewhat different view of the four elements, suggesting that the Great Four were instead mutable, as manifested qualities of what he called the primary matter of the universe, that again was not original. None were, and none could have been (save for the originality of expression through language, or poetry, or drama) for the elements themselves – as the most ancient of histories about them as can be found in the cultures both extant and (apparently) extinct upon the earth testify to – caused their characteristics and activities to become known, and given names, as we shall see3.

We cannot begin at the beginning, because there are many beginnings, and so few of them have even been ascribed as such. But because the great-grandparent roots of our most durable memories tell us that time is cyclical, and because in the search for a ‘beginning’ we can go only to an opposite point in the spiral of the cycle of time, we can at best call that opposite point one of the deeps of time (there are indeed so many). And at one of these points (they are infinite) humans began to see in a slow way (but because it was slow its teaching lasted very long, finding a voice again, after many earlier voices, that the Western tradition calls classical antiquity) that plants and forests and grasslands, that birds and animals and those finned and other creatures who dwell in the waters riverine or pelagic, that waters themselves whether rivers and streams or whether lakes and tarns and oceans that span the horizons of a generation, that gales and storms and typhoons and cyclones, that ice and dry sandy wastes, that fen and bog and arid scrub, that every manifestation of nature that could be observed and had been given a name (or names that had been forgotten) was an admixture of the Great Four, but more often the Great Five, and had its own spiritual nature and will, its motions and characteristics, its influences and its favourites.

There was, as much in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE as during the early, high and late Middle Ages of Europe (and their corresponding eras in non-European lands and territories) and then again during the Renaissance, a fount of wisdom, considered to be ancient at any and all of those times, from which sprang the idea of the Tetrasomia and its offspring. The ways in which this fount of wisdom came to be translated and employed was then given sundry names, some in those centuries and several more in the centuries that followed: animism, pantheism, polytheism and combinations thereof. It is these that can be found at the roots of most cultures, verily they must be there in all cultures that have a tetrasomia, or a pentasomia, of their own. At least until the end of the 20th century, there remained a large number of living cultures that were still true to these roots.

In conceiving the elements, tetra or penta, and in divining the uses of the materials, the fluids, the forces visible and invisible, arts were bound up. These were the three primary arts presented in the opening vignettes of this essay – for these three sustained cultures and civilisations – and were accompanied by others, marginally less vital but no less artful, and usually considerably more so, the building arts, metalworking, astrology and others. In every age during which cultures possessed a somia, and set great store by such a possession, the arts it inspired were bound together with the prevailing religious tendency and current philosophies about Nature and its meaning for our sojourn upon this Earth.

In the middle ages – sometimes also called the “ages of faith” and otherwise somewhat arbitrarily divided into the early, high and late middle ages4 – what was occluded or unseen or indeed was hidden with deliberateness, nonetheless cast strange lights and shadows on the minds and works of those ages’ thinkers and experimenters. Under this influence, that reached out effortlessly from beyond recent centuries, so it seemed, natural forms were altered, substance and representation of substance took on shifting and evanescent aspects.

Although the fount of wisdom, that was already very old at the dawn of what came to be called early antiquity, was unquenchable and inexhaustible, its very existence was sought to be obscured in all manner of ways. These had to do with the idea of the transformation of European society, and its institutions, from late antiquity to the early middle ages. It was, to put it very simply, the transformation from the pagan late Roman empire to the hegemony of the Christian set of beliefs and practices. One of the first such ways of obscuring the fount, if not diverting the curious away from it, was to affix the label ‘barbarian’ to it, so causing it to ontologically be assigned lesser worth, if at all any, and therefore not worth pursuing. As formulated by André-Jean Festugière in his monumental La Révélation d’Hermès Trismégiste, “The ruling idea was that the Barbarians possessed purer and more essential notions concerning the Divine, not because they used their reason better than the Hellenes but, on the contrary, because, neglecting reason, they had found ways of communicating with God by more secret means.”5

This view came to be called the ‘ancient wisdom narrative’ (such as by Wouter J Hanegraaff, the expert on the history of Hermetic philosophy at the University of Amsterdam) to understand which, he said, “we need to overcome such normative biases, which judge religious practices and speculations by the unsuitable yardstick of rational philosophy and anachronistically project modern stereotypes of ‘the occult’ back into the ancient past”6. At some point then, or rather at several points (for the transformation of late antiquity into the early middle ages certainly did not take place all at once across the entirety of what we today call Europe, but which took place slow and hesitating, from one valley to another, from one burg to the next stadt, from a monastic demesne here to a peatland encampment there) the philosophical content of these traditions itself came to be called pagan and pre-Christian and then in a matter of uneasy decades, were called ‘occult’ and beyond the pale of European Christianity. And when that happened, the gnostic, hermetic and related platonic religiosities of the earlier age and ages (the antiquities) were caused to fade from the minds and sight of men.

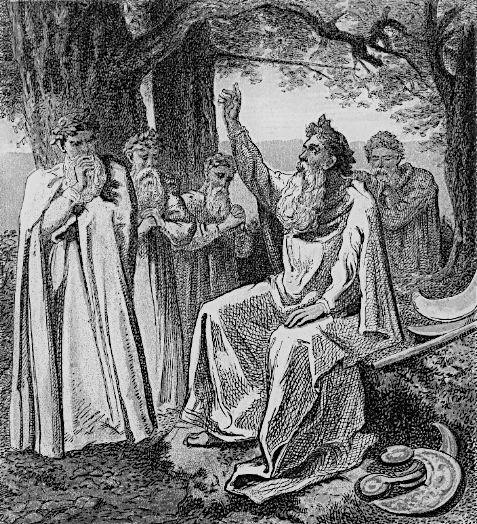

Then too, what was taken to have faded away into a bylane of history had only retreated, away from the glare of change brought in by the new religiosities. As always, a good place to retreat into was the forest. And here the druidical practices and considerations continued relatively undisturbed. For the druids, water was the first principle of all things and existed before the creation of the world in unsullied purity. Water was venerated by them because it afforded a symbol, by its inexhaustible resources, of the continuous and successive benefits bestowed upon the human race and because of the mystical sympathy existing between the soul of man and the purity of water.

They regarded the air as the residence of beings of a more refined and spiritual nature than humans (and with such regard allied their consideration of the beings of air very much, a tantalising alliance that reached over distance, with the Hindu conceptions about the dwellers in realms other than those perceivable by ordinary human senses). Fire they looked upon as a vital principle brought into action at the creation. Ceres, the goddess of agriculture, was originally a fire deity, and one of her early names was Cura, a title of the sun. In her towers the sacred fires were perpetually kept alight (an echo, just as tantalising of the famed fire worshippers of ancient Persia, the sacred structures of the Mazdayasnis and the Zoroastrians) and in them too was corn stored, a secondary usage, but no less important for the life-cycle of the grain-spirit.

Fire dictates its own ceremonies. According to Strabo and Pliny, fire rites were practised in ancient Latium (the west-central region of Italy that includes Rome), and a custom, which remained even to the time of Augustus, consisted of a ceremony in which the priests used to walk barefooted over burning coals (as much a rite properly Eastern and Oriental). The earth was venerated by the druids because it was the mother of mankind, and particular honour was paid to trees because they afforded a proof of the immense productive power of the earth. For many centuries the druids refused to construct enclosed temples, regarding it as an outrage to suggest that the Deity could be confined within any limits, and the vault of the sky and the depths of the forest were originally their only sanctuary7.

The ruling idea was that the most ancient ‘barbarian’ peoples possessed a pure and superior science and wisdom, derived not from reason but from direct mystical access to the divine, and that all the important Greek philosophers up to and including Plato had received their ‘philosophy’ from these sources. What had the Hellenic world (the Helladic, Cycladic, Minoan, Aegean, Mycenean) thought of the druids? We can scarcely guess, although it is impossible that the one – the druidic fellowships – did not know of the other and vice versa. Had the Hellenic mind assigned to these European rishis too the barbarian label? Perhaps politically, but I cannot imagine that this was also done by the natural scientists and hierophants of the ancient Greek cultures.

But the spoor of the European ‘barbarians’ ran very far back indeed. There were Varna on the Black Sea coast of today’s Bulgaria, Ovcharovo of the lower Danube region, the Tripolye culture site of Kolomischiina west of the Dnieper river in present-day Ukraine, Brześć Kujawski which was west of the Vistula river in the lowlands of north-central Poland, the rondels of the Carpathians (in Behemia, Moravia, Slovakia)8. These and a legion of other locations – from the Iberian peninsula to the western banks of the Volga river and up to Lake Ladoga – betokened cultures that had been very familiar indeed with the tetra and penta somias, and that at least some 3,500 years before the early Hellenic age.

The answer then, to the question – what wells of old wisdom did the thinkers and philosophers of the Greek and Roman age plumb? – is: an earlier age and very much more likely, the whispered rumours of earlier ages carried forth into their own by intellectual savants who cared not to be named. That is why there are to be found very many testimonies which confirm that Plato himself and all his notable predecessors had personally travelled to Egypt, Babylon, Persia and India, where they had studied with the priests and sages, with magi and rishis9. Not only was Greek philosophy seen as derived from (or inspired by, or having taken instruction from) oriental sources, ‘philosophy’ was well understood to be much more than the pursuit of knowledge by unaided human reason; its true concern was divine wisdom and the salvation of the soul (atman).

Numénius d’Apamée, or Numenius of Apamea, the Platonist philosopher of the mid-second century CE, embodied what came later to be called the ‘philosophia perennis’, the flow of ancient wisdom, at times hidden, and which at other times took shape and form in a language and idiom as cast into the public by a philosopher or thinker in whom, at that time, the very voices of the elements, the ‘philosophia perennis’, emerged. According to Henri-Charles Puech, Numénius was looking for “a philosophy without schools or factions, and, one might add, without history: a wisdom modeled after the transcendent God, which, like him, would remain above time, residing in the peace of an absolute immutability”10.

The will of the elements and their power caused even Eusebius – the bishop of Caesarea during the early fourth century and the author of Historia Ecclesiastica – to cite Numenius’ famous postulate that when seeking the truth one should take into account diverse sources: from the ‘testimonies’ of Plato, through the ‘teachings’ of Pythagoras, to the ‘rites’, ‘beliefs’ , and ‘consecrations’ of the Brahmans, Jews, Magi, and Egyptians. This suggests that Numenius would select those ideas that appeared to him useful for extracting ancient wisdom: Plato confirmed what Pythagoras revealed but the truth could also be discerned in the various cultural practices of non-Greek peoples11.

In this way, the great schools of the ‘philosophia perennis’, the perennial flow of ancient wisdom, were formed and re-formed, waned in one century only to bloom once again in the next. Visible as schools and with accomplished masters when the times and temporal powers were benign towards them, and sent into exile or underground (occluded) when those powers turned against them, intolerant and vicious, this is how they journeyed through the centuries from high and late antiquity through the various stations of the Middle Ages and thence to the very threshold of the Renaissance and beyond, into what came to be called early modern Europe.

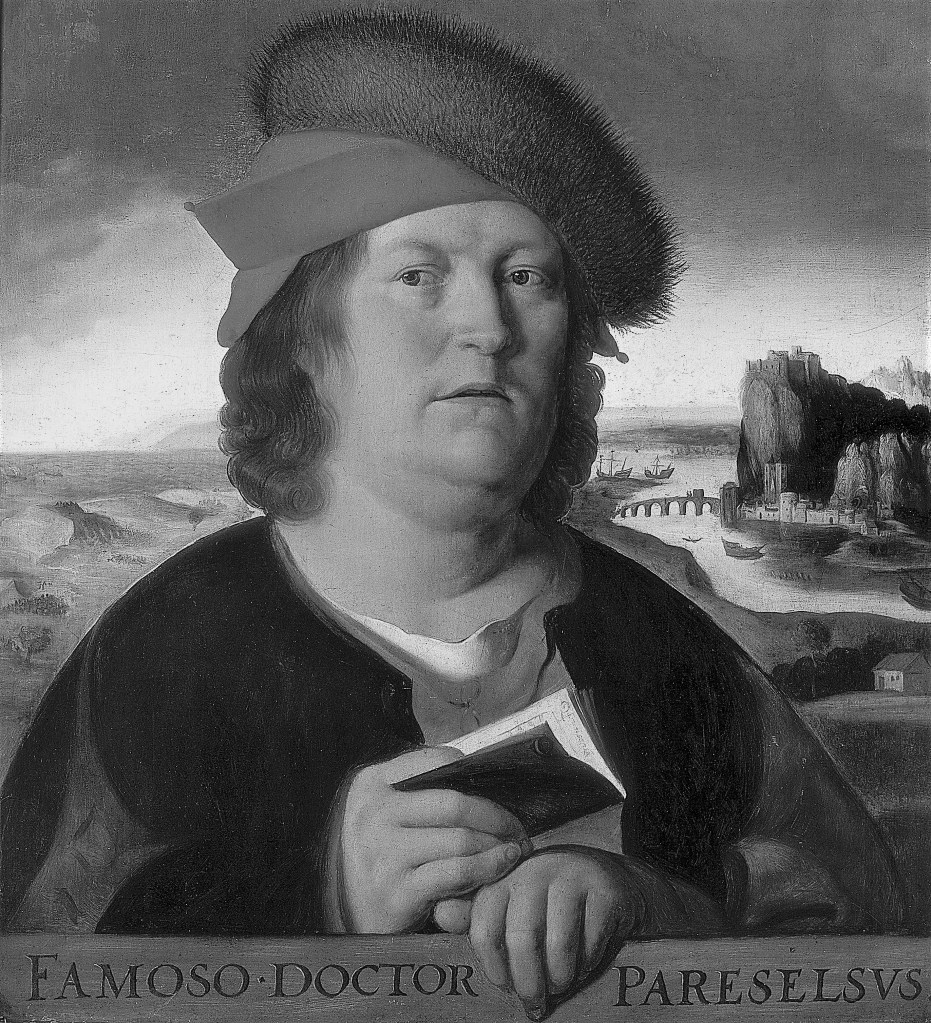

And so it was that Paracelsus (Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, whose daunting body of writings are the second largest 16th-century corpus of writings in German after Luther’s, for he contributed to medicine, natural science, alchemy, philosophy, theology, and esoteric tradition) gave names, in his Liber de Nymphis, to the elementals: salamanders are the beings of fire, sylphs are the beings of the air, undines are the beings of water, gnomes are the beings of earth12. In so doing, Paracelsus steered by the tetrasomia, as did the Polish alchemist Michal Sedziwoj, also known as Sendivogius, who in his work NovumLumen Chymicum (1605) had explained: “There are four common elements, and each has at its centre another deeper element which makes it what it is. These are the four pillars of the world. They were in the beginning evolved and moulded out of chaos by the hand of the Creator; and it is their contrary action which keeps up the harmony and equilibrium of the mundane machinery of the universe; it is they, which through the virtue of celestial influences, produce all things above and beneath the earth.”

Here then are the written testimonies noted by some of the most intuitive and receptive minds in as late as the 16th century of the common era, about the elements being the pillars of the world, of their having names and assuming forms so as to be discerned by man’s senses (feeble though they are), of chaos, equilibrium, the machinery of the universe, the hand of the creator, the presence of a deeper element. These I see as more than clues that show us the borrowing and exchange of concepts and practices between ‘East’ and ‘West’. No, they are far more, because the ‘philosophia perennis’, the perennial flow of ancient wisdom, and those who became steeped in it, observed no such boundaries and regions such as ‘East’ and ‘West’, quite simply for the elements roamed and sported at will across, under and above the surface of the earth.

Well were the elements so known, although seldom were they so formally studied, described and employed in the ‘West’. Within the many circles of natural science and esoteric traditions that fermented still even in the period known as early modern Europe, the elements were considered as transcendent forces, as full of grace as they were of power incomprehensible. “The singular part of the Elements gains its partial Elemental status only by virtue of the arrangement of each in its position and by whatever internal accidental effects, which it may be subjected to, that pertains to its particular characteristics in this state,” so runs a passage in the very curious book called The Goal of the Wise, which was the Ghayat al-Hakim in translation, the entirety of which had been rendered into English from the Arabic by Hashem Atallah, and which became commonly, even notoriously, known as the Picatrix. “Water, for example, gains its wet and cool nature by its position and whatever adjoins it in the world order. However, its existence prior to its Element status survives as a whole. These totalities exist by nature whether perceived mentally and discovered by man or not.”

Having found a bridge (although truly none is needed, if only for one formal crossing, and thereafter the division between ‘East’ and ‘West’ dissolves, as does the one between pagan and whosoever, or whatsoever, calls it pagan) the consideration of the elements becomes more organically automatic. The Taittiriya Upanishad comes into view, which tells us that any creation, whether cosmic, of the human body, or of art, has to start from the five elements: earth, water, fire, air, space, for they are conceived of as the essentials of the universe and of the human body alike. This Upanishad gives the elements in their sequence (according to ancient Indian thought of the Vedic age) which proceeds from the subtle to the gross: akasa (space), vayu (wind), agni (fire), ap (water), prithvi (earth).

Whether physically or symbolically, they constitute primary and indispensable categories of reality (tattva). The elements are never seen only at their gross, material level because they contain a subtle as well as divine level. “The basic concept of prakrti, primal nature or materiality, which is so to say the matrix of all the elements, gives the general background to the understanding of nature.” Such is the exposition offered by Kalatattvakosa, A Lexicon of Fundamental Concepts of the Indian Arts13. This is the system of correlations between the Vedic and Tantric worldviews (the bridge that has been crossed has itself dissolved) , as also in Buddhist and Jaina thought, all based on the primordial elements.

I have ventured this far into the region that lies between ‘East’ and ‘West’ because it had appeared, dimly at first some years ago, and lately with greater luminescence, that the ‘philosophia perennis’ washes through and around all. It encircles the known and unknown (the mysteries of old) in the way that Okeanos was the world-girdling sea, which caused all water to arise and to which all water returned. And to call once again upon the first representative characters in this essay – the craftspeople, traditional healers and medicators, cultivators and farmers – the very great number of their fraternities and sororities wanted to be noted neither as philosopher nor thinker nor celebrated theologian nor stately eminence.

“For thousands of years civilised nations, as well as the most barbarous tribes, if we except a few savage hordes, cherished, denounced, and endeavoured to protect themselves against the power which they believed was granted to some men to change the common course of nature, through the medium of certain mysterious operations.” So had mused Eusèbe Salverte a little under two centuries ago in Des sciences occultes. Essai sur la magie, les prodiges et les miracles (The Occult Sciences. The Philosophy of Magic, Prodigies and Apparent Miracles). And in like manner, those closest to the forms of the elements, who could hear their cosmic tones and who contemplated at length their inner transmutations, came to adopt and then fashion a language of living sign and living symbol.

In this way, they served not only their brethren, but the elemental deities of old – Odin, Thor, Baldr, Freyr, Heimdal, Bran, Apollo, Hephaestus, Poseidon, Jupiter, Ceres, Artemis, Rudra, Vishnu, Parjanya – and in so doing were carried, as the Tantraloka tells us of those who hear the voices of the elements, “to vast expansion”.

1 ‘Practical Elemental Magick, A practical guide to working with the four elements – Air, Fire, Water & Earth – in the Western Esoteric Tradition’, David Rankine and Sorita D’Este, Avalonia, 2008

2 “Although he is commonly considered one of the founders of Western science and philosophy, it is better to view him as an ancient Greek “Divine Man” (Theios Anêr), that is, a Iatromantis (healer-seer, “shaman”) and Magos (priest-magician). In his own time he was viewed as a prophet, healer, magician and savior. His beliefs and practices were built on ancient mystery traditions, including the Orphic mysteries, the Pythagorean philosophy, and the underworld mysteries of Hecate, Demeter, Persephone and Dionysos. These were influenced by near-Eastern traditions such as Zoroastrianism and Chaldean theurgy. Empedocles, in his turn, was a source for the major streams of Western mysticism and magic, including alchemy, Graeco-Egyptian magic (such as found in the Greek magical papyri), Neo-Platonism, Hermeticism and Gnosticism. The Tetrasomia, or Doctrine of the Four Elements, provides a basic framework underlying these and other spiritual traditions.” So John Opsopaus has written on his website (see http://opsopaus.com/OM/BA/AGEDE/Intro.html) referring Ancient Philosophy, Mystery and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition, Peter Kingsley, Oxford University Press, 1995.

3 ‘On Nature‘ is based on the premise that everything is composed of “four roots”, these are moved by two opposing forces, Love and Strife.

“Hear first of all the four roots of all things:

“Zeus the gleaming, Hera who gives life, Aidoneus,

“And Nêstis, who moistens with her tears the mortal fountain.”

Since the roots are identified by the names of deities — and not by the traditional names for the elements fire, earth, air, and water — there are rival interpretations of which deity is to be identified with which root. Nevertheless, there is general agreement that the passage refers to fire, earth, air (aither, the upper, atmospheric air, rather than the air that we breathe here on earth) and water. Aristotle in ‘Metaphysics’ credits Empedocles with being the first to distinguish clearly these four elements. However, the fact that the roots have divinities’ names indicates that each has an active nature and is not just inert matter. These roots and forces are eternal and equally balanced, although the influence of Love and of Strife waxes and wanes.

For a full treatment of Empedocles see https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/empedocles/

4 In his introduction to the history of Europe 500-700 (Volume 1 of The New Cambridge Medieval History, 2005), editor and contributor Paul Fouracre wrote:”At our starting point around the year 500, we may still characterise European culture as ‘late antique’; by the year 700 we are firmly in the world of the Middle Ages. A transformation has apparently occurred. The idea that it is developing consciousness that calls changes into being is not far off the mark either, if we think about the triumph of the Christian future over the pagan past and the reconfiguration of culture and institutions around newly hegemonic religious beliefs and practices.” What we see here is a ‘transformation’ that marks out late antiquity from the onset of what in our era we have become apt to call middle ages.

5 André-Jean Festugière (1898-1982) was a French Dominican and historian. After classical studies, which led him to study the ancient languages of the Middle East, he entered the Dominican order in 1924, after having belonged to the French School of Rome (1921) and then to that of Athens (1922), and devoted himself to the analysis of Greek thought (L’Idéal religieux des Grecs et l’Évangile, 1932; le Monde gréco-romain au temps de Notre-Seigneur, 1935). He then translated and commented on the Corpus hermeticum (La Révélation d’Hermès Trismégiste, 4 volumes, 1944-1949).

6 ‘Esotericism and the academy: rejected knowledge in western culture’, Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Cambridge University Press, 2012

7 ‘Druidism, the ancient faith of Britain’, Dudley Wright, J. Burrow & Co. Ltd., 1924

8 See ‘Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: encyclopedia of the Barbarian world’, Peter Bogucki and Pam J. Crabtree, editors, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2004

9 In his monumental writings on the great monarchies of the ancient Eastern world, George Rawlinson has this to say (in the volume on Media): “The tie of a common language, common manners and customs, and to a great extent a common belief, united in ancient times all the dominant tribes of the great plateau, extending even beyond the plateau in one direction to the Jaxartes (Syhun) and in another to the Hyphasis (Sutlej). Persians, Medes, Sagartians, Chorasmians, Bactrians, Sogdians, Hyrcanians, Sarangians, Gandarians, and Sanskritic Indians belonged all to a single stock, differing from one another probably not much more than now differ the various sub-divisions of the Teutonic or the Slavonic race.” And so we see that because the Jaxartes and the Hyphasis have been so named by the Greeks, the ancient peoples mentioned in Rawlinson’s tomes, and their customs and manner of thought, were known to the Greeks and their philosophers.

10 Puech, H. C., 1934, “Numenius d’Apamée et les théologies orientales du second siècle”, in Mélanges Bidez, Brussels: Secretariat de l’Institut, vols. I–II

11 See Domaradzki, M. (2020). OF NYMPHS AND SEA: NUMENIUS ON SOULS AND MATTER IN HOMER’S ODYSSEY. Greece & Rome, 67(2), 139-150. doi:10.1017/S0017383520000030

12 In his 16th-century alchemical work Liber de Nymphis, sylphis, pygmaeis et salamandris et de caeteris spiritibus, Paracelsus identified mythological beings as belonging to one of the four elements. Part of the Philosophia Magna, this book was first printed in 1566 after Paracelsus’ death. He wrote the book to “describe the creatures that are outside the cognizance of the light of nature, how they are to be understood, what marvellous works God has created”.

13 In volume 3 of Kalatattvakosa, A Lexicon of Fundamental Concepts of the Indian Arts, compiled and published by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts and Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1996.